|

November 16, 2014: Return to Quito |

|

November 14, 2014: San Cristobal Island |

|

Return to the Index for Our Galapagos Adventure |

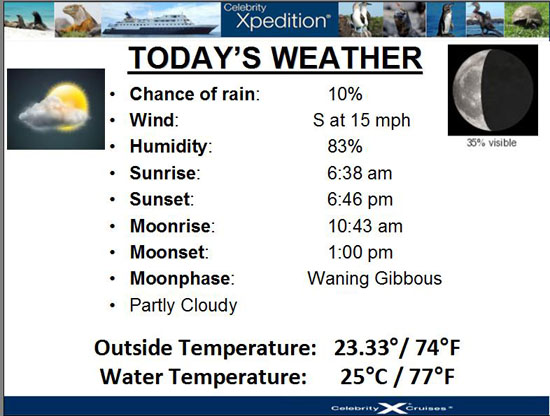

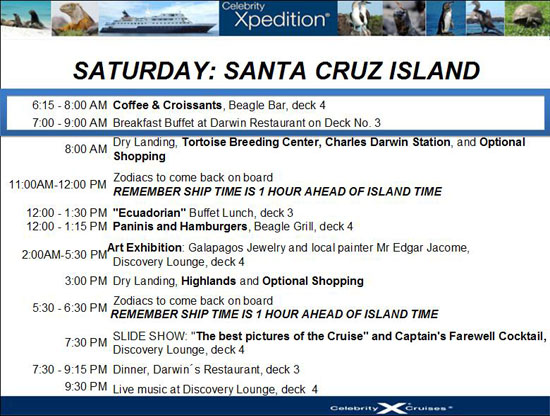

We will be up early for our last full day here in the Galapagos Islands. After breakfast on the ship, we will be ferried in to Puerto Ayora on the island of Santa Cruz.

|

|

This will be our last day in the Galapagos, and we will concentrate today on the one Galapagos native we have not yet seen- the giant tortoise.

|

Once we disembark, a Celebrity-provided bus will shuttle us to the Darwin Research Station. Actually, it will drop us off a quarter-mile from the actual entrance. After we spend a couple of hours at the Station looking at the tortoises there, we will walk on our own back to a waterfront location in town where another bus will take us north to the Santa Cruz Highway (the one that comes down from the north side of the island) and then three or four miles almost to the center of the island where we will each have the opportunity to participate in reforestation by planting a couple of scalesia trees.

Following that, the bus will take us south of the main road to El Rancho Manzanilla, which is a giant tortoise preserve, and part of the national park. Here, we will have lunch and then spend some time clomping around the preserve looking at the tortoises that roam freely here.

We will finish the day by returning to Puerto Ayora and doing a little sightseeing in the town before hopping back in a Zodiac to return to the Xpedition.

Galapagos Shore Excursion (15a):

The Darwin Research Station

|

| "The Darwin Research Station concentrates on the giant tortoise. Using tortoise eggs brought from other islands, the Station incubates and hatches them and then protects them for about five years. Now able to survive the threat of introduced predators, they are returned to their native areas. You will get a chance to see these programs in action, observing tortoises from only a few months old to young adults five years old and more. Your naturalist guide will explain the programs and answer questions. You will have time to wander around the Station on your own, observing its activities; perhaps you will spot other residents of the station- such as land iguanas, lava lizards and Chatham mockingbirds- and also learn about some of the flora of Santa Cruz. Duration: About 3 hours" |

Getting from the Xpedition to the Darwin Research Station

|

Right at the end of the pier, we found ourselves in Parque San Francisco; the bus that would take us to the Darwin Station picked us up right nearby. After a circuitous drive through town (necessitated because the direct street to the Station, Darwin Avenue, is one-way in the wrong direction), the bus dropped us all off at a point about a quarter-mile from the actual entrance. Here, we grouped around our naturalist and he gave us some info on what we would be doing.

While he was talking, I listened with one ear while wandering over to photograph a souvenir shop that had not opened yet. Opposite the shop, the was an area inside low whitewashed walls, and it turned out to be a local cemetery.

We all headed off together up the street towards the entrance to the research station, with our naturalist answering questions as we walked.

Entering the Darwin Research Station

|

A short ways past the entrance station, our naturalist took us off on a path that led away from the street (which continues up to the museum and administration buildings) and out to the area where the giant tortoises were. Click on the thumbnails below to see some of the pictures we took along the way:

|

We also found some beautiful yellow flowers, as well as an informational sign entitled "Solar energy for the giant tortoises" that you might be interested in reading. We passed a sign that had a little diagram of the main pathways through the giant tortoise area and then came to one of those pathways that we took to the first of the tortoise enclosures. You can see both those pictures below:

|

|

Giant Tortoises- Main Enclosure

|

Today, they exist only on two remote archipelagos: the Galápagos and Aldabra in the Indian Ocean. The tortoise is native to seven of the Galápagos Islands. In fact, the Spanish word "galápago" means "tortoise". Tortoises (like cats, it seems) live very uncomplicated lives, and can nap up to 16 hours a day.

Click on the thumbnails below for some more views of the juvenile tortoises in this main enclosure at the Darwin Station:

|

Tortoise numbers declined from over 250,000 in the 16th century to a low of around 3,000 in the 1970s. This decline was caused by exploitation of the species for meat and oil, habitat clearance for agriculture, and introduction of non-native animals to the islands, such as rats, goats, and pigs. The extinction of most giant tortoise lineages is thought to have also been caused by predation by humans or human ancestors. Tortoise populations on at least three islands have become extinct in historical time due to human activities. Specimens of these extinct taxa exist in several museums and also are being subjected to DNA analysis. Ten subspecies of the original fifteen survive in the wild.

|

Shell size and shape vary between populations. On islands with humid highlands, the tortoises are larger, with domed shells and short necks; on islands with dry lowlands, the tortoises are smaller, with "saddleback" shells and long necks. Charles Darwin's observations of these differences on the second voyage of the Beagle in 1835 contributed to the development of his theory of evolution. Darwin was highly impressed by these giants, although he referred to them as “antediluvian” and “giant monsters”- less than affectionate terms.

Here are thumbnails for four pictures I took of these huge reptiles:

|

Two of the first movies that Fred made of the giant tortoises were of them eating. The first one was from a distance and the second close up. The players for these two movies are below. The tortoises are herbivores that consume a diet of cacti, grasses, leaves, lichens, and berries. They have been documented feeding on the endemic guava, the water fern Azolla microphylla, and the bromeliad Tillandsia insularis. Juvenile tortoises eat an average of 15% of their own body weight in dry matter per day, with a digestive efficiency roughly equal to that of other herbivorous mammals such as horses and rhinos.

|

|

|

Tortoises acquire most of their moisture from the dew and sap in vegetation (particularly the cactus). This means that they can survive up to six months without actually drinking water. Observation has revealed that they can subsist and endure for the better part of a year if no food or water is available. They do so by breaking down their body fat to produce water as a by-product.

Tortoises also have very slow metabolisms. When thirsty they may drink large quantities of water very quickly, storing it in their bladders and in special structures at the base of their necks. They then draw on this water as they need it. This interesting fact actually led some ship captains to take tortoises that had filled these structures with water on board their ships, and using them as water sources in emergencies. On arid islands, tortoises lick morning dew from boulders, and the repeated action over many generations has formed half-sphere depressions in many rocks that one sees in areas where the tortoises spend their time.

|

The Galápagos Islands were discovered in 1535, and first appeared on maps about 1570. The islands were named "Insulae de los Galopegos" (Islands of the Tortoises) in reference to the giant tortoises found there. Initially, the giant tortoises of the Indian Ocean and those from the Galápagos were considered to be the same species. Naturalists thought that sailors had transported the tortoises from one location to the other. But in 1834, the first taxonomists classified the Galápagos tortoises as a separate species.

|

Up to 15 subspecies of Galapagos tortoises have been identified, although only 11 survive to this day. Six are found on separate islands; five of them on the volcanoes of Isabela. Several of the surviving subspecies are seriously endangered, and one subspecies went extince when the last known specimen, "Lonesome George" died in captivity in 2012.

All of the Galapagos tortoises have a large bony shell of a dull brown color. The plates of the shell are fused with the ribs in a rigid protective structure that is integral to the skeleton. Tortoises keep a characteristic shell segment pattern on their shell throughout life, though the annual growth bands are not useful for determining age because the outer layers are worn off with time. A tortoise can withdraw its head, neck and forelimbs into its shell for protection. The legs are large and stumpy, with dry scaly skin. The front legs have five claws, the back legs four.

|

|

The size of these tortoises is an interesting topic for scientists. It was originally supposed that they were normal sized when they arrived but grew large in response either to lack of predation or for some other reason. But most experts now think that the tortoise's size is an example of a "preadapted condition". These scients think that large tortoises would have a greater chance of surviving the journey over water from the mainland; larger animals could hold their heads a greater height above the water level and would have a smaller surface area/volume ratio- reducing water loss. Their significant water and fat reserves would allow them to survive long ocean crossings without food or fresh water, and to better endure the drought-prone climate of the islands. Finally, a larger size would allow them to better tolerate extremes of temperature.

Another hot debate topic (well, "hot" among those who study the giant tortoise) concerns the different shell shapes- domed or saddleback. The most common reason put forward for the existence/evolution of this shape is that it would tend to allow the animal to stick its neck out vertically and thus reach higher vegetation- notably the tree-form cactus that exists in the arid climate.

|

On the larger and more humid islands, the tortoises seasonally migrate between low elevations, which become grassy plains in the wet season, and meadowed areas of higher elevations in the dry season. The same routes have been used for many generations, creating well-defined paths through the undergrowth known as "tortoise highways". On these wetter islands, the domed tortoises are gregarious and often found in large herds, in contrast to the more solitary and territorial disposition of the saddleback tortoises. Tortoises sometimes rest in mud wallows or rain-formed pools, which may be both a thermoregulatory response during cool nights, and a protection from parasites such as mosquitoes and ticks.

And, of course, they make little tortoises.

Mating occurs at any time of the year, although it does have seasonal peaks. When mature males meet in the mating season they will face each other in a ritualised dominance display, rise up on their legs and stretch up their necks with their mouths gaping open. Occasionally, head-biting occurs, but usually the shorter tortoise will back off, conceding mating rights to the victor. The behavior is most pronounced in saddleback subspecies, which are more aggressive and have longer necks.

|

Females journey up to a couple of miles in July to November to reach nesting areas of dry, sandy coast. Nest digging is a tiring and elaborate task which may take the female several hours a day over many days to complete. It is carried out blindly using only the hind legs to dig a one-foot deep cylindrical hole, in which the tortoise then lays up to sixteen spherical, hard-shelled eggs the size of a billiard ball. The female makes a muddy plug for the nest hole out of soil mixed with urine, seals the nest by pressing down firmly with her undershell, and leaves them to be incubated by the sun. Females may lay 1–4 clutches per season.

We'll learn more about what happens when the eggs hatch a bit later on.

We mentioned that tortoises can move at .2 MPH, but in reality, they move a lot slower than that. I followed one tortoise first as it moved behind a group of other tortoises and then later on as it climbed a few feet on the rocks. Use the players below to watch those movies:

|

|

|

We must have spent a half hour listening to the naturalist and looking at the giant tortoises; they were pretty amazing animals.

|

|

Finally, here at the habitat for the juvenile tortoises, we have two more movies of note. With the left-hand player below, watch Fred's movie of a giant tortoise and the most amazing yawn you've probably seen. With the right-hand player, watch my movie of a tortoise caught with his mouth full:

|

|

|

Land Iguanas

|

We'd seen a lot of land iguanas over on Santiago Island, so all I'll do here is put clickable thumbnails for the other two good pictures we took here at this small enclosure:

|

On the Boardwalk Through the Giant Tortoise Enclosure

|

|

There are thumbnails below for some of the pictures we took here on the boardwalk as we made our way around it:

|

The boardwalk made a long curve around to the tortoise nursery- our next stop.

The Galapagos Prickly Pear

|

|

|

The tree cactus you see here is opuntia echios and is a species of plant in the Cactaceae family. It is endemic to the Galápagos Islands; there are also five other species of prickly pears that also are endemic to the archipelago. Within the species opuntia echios there are five varieties. The views above are of the variety "gigantea" which is endemic only to this area near Academy Bay on Santa Cruz.

The Tortoise Nursery and Adaptation Pens

|

Newborn tortoises are kept in those terrariums for the first two years of life, to protect them from possible predators such as rats. Then they move to the adaptation pen, where they will stay until the curvature of their shells grows to ten inches or so, which means an age of approximately 4 to 6 years.

Click on the thumbnails to see some other pictures of the adaptation pen:

|

To avoid mistakes, tortoises are marked with color-coded paint to show their islands of origin and each individual's number.

|

We took quite a few pictures of the tortoises in the natural area; they were about the size of very large box turtles. You can click on the thumbnails below to see some of these pictures:

|

Packed safely in wooden boxes, the tortoises travel by land and sea to their island of origin where they are released near existing tortoise population sites. Before being released, the tortoises are measured, weighed and permanently marked with PIT tags- small microchips inserted under the skin. These "bar codes" allow scientists and park wardens to track the progress of each animal, its growth rate, location, distribution and a female's reproductive status, if she is found again.

Visitors to the Research Station

A Galapagos Mockingbird |

A Lava Lizard |

Leaving the Charles Darwin Research Station

|

|

Before we headed off back towards our meeting point in Puerto Ayora, I took one more picture here- a panoramic view of the new Visitor Center:

The Visitor Center |

Galapagos Shore Excursion (15b):

The Town of Puerto Ayora

At that point, I put together a panoramic view (in which you can see some of the subjects of the individual pictures below). In the view, the road up to Darwin Station is at right, and Darwin Avenue into Puerto Ayora is at left:

|

From there, we continued along Darwin Avenue walking into Puerto Ayora.

|

We took a number of pictures along our walk- interesting shops, sculptures, fountains and such- and you can use the thumbnails below to have a look at some of them:

|

About halfway into town, I stopped at another intersection to do another panorama. Again, Darwin Avenue comes into the panorama from the right and is the street leading out to the left:

|

And just before we got to the fish market, I found one long series of shops in a single building that I wanted to photograph. I could not get back far enough to get it all in, so again, I had to construct a panoramic view out of three separate pictures:

|

There was a lot of colorful stuff to see along our walk, although sometimes we weren't sure of the purpose of some of the art! About a block from where the bus was to pick us up to continue our shore excursion, we came to the local fish market, where boats come and unload their catch and it is cut and prepared for individuals, stores and restaurants.

|

The fish market was an active place; there were three or four people working at preparing the fish. But what made it really interesting was that there were a few sea lions and a large number of pelicans flopping and walking around looking for handouts, which they occasionally were given or, in one instance, simply took. Indeed, the various animals took away any waste from the preparation process, relieving the fishmongers from the chore of discarding it! There are thumbnails below for a few of Fred's pictures of the activity here:

|

From the pictures, you can see that there was a lot going on, and I snapped a picture of some lobsters being weighed. In one of Fred's pictures above, you can see a sea lion with his head up on the preparation surface; I happened to be around the other side of the stall and caught that same sea lion from the front.

|

|

I thought I had taken some movies, but apparently I didn't. Yoost, however, took a number of interesting pictures, and you can use the thumbnails below to have a look at some of them:

|

As you can see in this picture of Academy Bay taken from the fish market, there is a pier of some kind that is off to the right. I thought I might get some good pictures from there, so Fred and I went down the street a ways to find the walkway out to it.

|

We also found some wildlife, including a booby and some marine iguanas- plus a pelican hiding in the mangroves. If you would like to see some of these pictures, just click on the thumbnails below:

|

Before we left the pier, I used my camera's internal function to make a panoramic view of Academy Bay, and you can have a look at it below:

|

We left the pier and went back streetside, where we sat down with Yoost to wait for the time to board the bus for our ride out to plant some Scalesia trees. While we were waiting, Fred took a picture of the jewelry store across the street and also walked over to get a better view of the mosaic that was part of the wall decoration. He also came back with a picture of a placard advertising beer, which was pretty funny in that the beer company seemed to have found the perfect spokesanimal for it's them of "Relax". You can see that placard here.

Presently, our naturalist came to get us and we walked around the corner to board our waiting buses.

Galapagos Shore Excursion (15c):

Planting Scalesia Trees

|

Due to no competition on these areas, they flourished, and grew into towering trees. Due to their height, they are able to gather moisture from the air. This is helpful in the arid areas of the islands, and they also help the surrounding plants gather moisture. Plants around Scalesia trees gather moisture from water droplets running down the tree's trunk or leaves, this helps them grow alongside the tree, as dependents.

Scalesia is a genus in the family Asteraceae endemic here in the Galapagos Islands. It contains fifteen species that grow as shrubs or trees; tree forms are very uncommon in this family.

|

As you saw on the aerial view at the top of this page, our bus drove a good ways up into the hills, parking on the side of the road to let us out. We sat down at the side of the road (in a fine mist) to put on boots and then lined up on a path leading into the woods.

As we filed into the woods, one of the naturalists reached into a crate containing seedlings and handed each of us two seedlings- one a scalesia seedling (right) and the other a companion plant that has something of a symbiotic relationship to the scalesia.

Scalesia have soft, pithy wood, and have been called "the Darwin's finches of the plant world" because they show a similarly dramatic pattern of adaptive evolution.

|

|

Then we could each congratulate ourselves on a job well done.

The scalesia we planted should into trees up to sixty feet tall, and they will reach maturity in only a few years. These trees typically grow in dense stands of the same species and age. They die around the same time, and then a new generation of seedlings grows up in the same place. The largest stands of Scalesia are in the humid areas on Santa Cruz, San Cristóbal, and Santiago islands, and their altitude range is 1000-2000 feet. The stand we are working on expanding today is the most visited.

Once we'd shed our boots and turned in our trowels, we piled back into the buses for the short ride to Manzsnilla Ranch.

Galapagos Shore Excursion (15d):

Lunch at the Manzanilla Tortoise Preserve

|

The fruit was quite good; there were one or two items that I hadn't recognized right off; I learned later that one of them was a kind of pear. There was also more of that dark blue berry drink that we'd had in Quito. While we were waiting for the main buffet to be announced, Fred took a picture looking outside towards where we had come in; take a look at that picture here. Outside, you can see a covered area; this would turn out to be the place we'd go to get the boots that everyone is given to walk around the damp (and sometimes muddy) "pastures" to see the giant tortoises (tortoises we could already see through the plastic walls of the pavilion).

When the main buffet was opened up, we waited a bit so as not to have to stand in line too long. Then I held down the fort while Fred, Yoost and Greg went and got something to eat. As soon as Fred got back with his lunch, I went and got some as well.

Both Fred and I took a number of pictures during our lunch (which was quite good, by the way), and I'd like to include four of them here.

|

|

|

|

When everyone was well into dessert, the lunchtime entertainment began. It was a series of four dances representing various parts of Ecuador and the Andes, and they were performed by a group of some twenty young people. Each was interesting and fun to watch. Of course, both Fred and I took lots of movies and stills of each dance. For each dance, I've chosen the best of the movies we made of it, and also the best of the still pictures we took during it. Click on the player at left to watch the movie of a dance and on the thumbnails at the right to see the pictures.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Actually, there was a fifth dance- this one performed by the young dancers and as many of the audience who wanted to get up and participate. We took two movies; in the first one, each young dancer is paired with an audience member, while in the second one, the dance turns into a long conga line with some tunneling going on. You can watch these movies with the players below:

|

|

|

And below are thumbnails you can click to see some of the still pictures Fred and I took during the audience participation dance:

|

When the show was over and our lunch all finished, we all headed outside with our naturalist guides to put on some boots and walk around the preserve.

Galapagos Shore Excursion (15e):

Exploring the Manzanilla Tortoise Preserve

|

So I guess that Celebrity Cruises had booked the facility for out lunch today, and for the time we would spend here afterwards.

The area all around the pavilion is quite lush. This area gets a lot of rain, and so the grounds are usually either wet or quite damp. The fact that the tortoises (and there are a lot of them) are continually moving around helps create an environment that is usually muddy, and so folks like us who visit here are given boots to walk around in. That was the first thing we did- leave the pavilion to the covered area adjacent to pick out boots of the right size.

|

Across the road, there was a wide open field with some low bushes and a few trees, and beyond that large area a more heavily-wooded portion. We were going to explore around in the open area, and the first thing we noticed was that there were perhaps ten or fifteen giant tortoises that we could see out in that area. I was reminded of an Easter egg hunt as the tortoises dotted the landscape. There are clickable thumbnails below for some of our pictures of groups of these tortoises:

|

So we paired off in little groups, each with a naturalist in tow, and we walked out into that open field to get a better look at the tortoises. Of course, we were still reminded of the rules about getting too close to them, but we were able to get good pictures.

|

And below are clickable thumbnails for some of the best of our other individual tortoise portraits:

|

In addition to the pictures we took, I also made some movies. Now, there were only two reasons to make a movie here. The first was to show a tortoise in motion, of course. To watch them go any distance at all, you'd need a fairly long movie, but there is a player below for the movie I made of "tortoises in motion":

|

|

Walking around the area and getting as close to the tortoises as one is allowed was pretty neat- a lot different than this morning when all we could do was look at a few of them from a distance and in an enclosure.

|

|

I said earlier that there were only two reasons to film the tortoises. The second reason is to watch them eat. This is also a slow process, and only a little better than watching paint dry. Below, left, is a player that you can use to watch one of the tortoises doing his part to keep the lawn neatly trimmed. And right beside that player is a shot Fred got of him with his mouth full.

Tortoise Lawn Service |

|

I'll finish up our wanderings through the big open area with a final set of tortoise pictures. You can click on any or all of the thumbnail images below to see some of these images:

|

In late afternoon, the naturalists began to herd their charges back to the pavilion. There, we returned our boots and prepared to head back to Puerto Ayora.

|

One of these birds is in the picture at left, and you can see the rose and some other bird pictures if you click on the thumbnails below:

|

Eventually, we all piled into our buses and headed back to Puerto Ayora for the trip back to the Xpedition and our last night on the ship.

When we got back to the pier at Puerto Ayora, the Zodiacs were already showing up to ferry people back to the Xpedition. But I did have time to take my final picture from Santa Cruz- a panoramic view of Academy Bay:

|

Evening aboard the ship was occupied not only with our final dinner on board, but also with a farewell party held in the Discovery Lounge. We also had to pack our luggage and put it outside our doors before we went to bed; as with most cruises, that baggage was collected and transferred, in our case, all the way back to Quito.

You can use the links below to continue to another photo album page.

|

November 16, 2014: Return to Quito |

|

November 14, 2014: San Cristobal Island |

|

Return to the Index for Our Galapagos Adventure |