|

November 12, 2014: Santiago & Bartolome Islands |

|

November 10, 2014: Santiago & Rabida Islands |

|

Return to the Index for Our Galapagos Adventure |

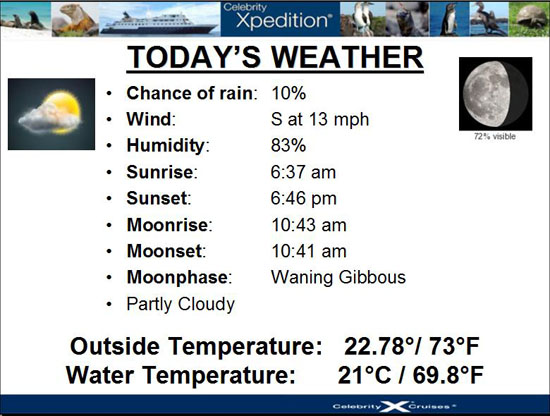

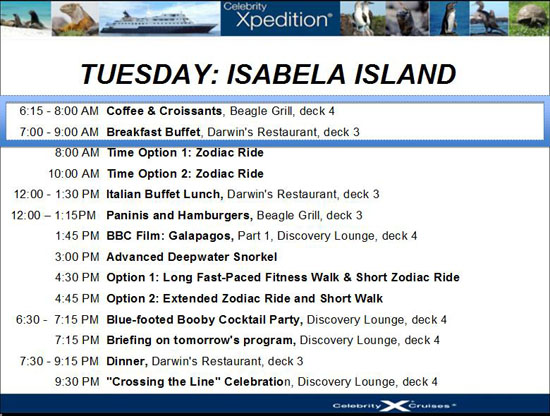

Today, we will be visiting Isabela Island, and we will have two excursions here. In the morning we will take a Zodiac ride through the mangroves to see how much wildlife we can spot. In the afternoon we will go on a fast walk on the island followed by another Zodiac ride.

Morning on the Celebrity Xpedition

|

|

This morning, there are two different Zodiac excursions to the mangroves- an early one and a late one. We decided to take the second tour, so we had plenty of time to have breakfast and relax before leaving the ship about 10AM.

|

We just took a few casual pictures on board this morning, and you can click on the thumbnail images below to have a look at them:

|

Just before 10AM, we went back to our stateroom to change for the Zodiac ride to the mangroves.

Galapagos Shore Excursion (3):

Cruising through the Mangroves at Elizabeth Bay, Isabela Island

|

| "Elizabeth Bay provides the perfect setting for a scenic zodiac ride and wildlife viewing. Within this sheltered mangrove-lined bay we may see Galapagos penguins, flightless cormorants, blue-footed boobies, herons, sea lions, and hawks. Shallow clear water reveals Green sea turtles, spotted eagle rays, stingrays and golden rays. It is a wildlife bonanza in this, the western region of the Galapagos. Duration: About 2 hours" |

From the Xpedition to the Mangroves

|

As with all our excursions throughout the week, we were accompanied and led by one of the eight or ten naturalists that sail aboard the Xpedition each week. This is Carlos, our naturalist for the morning. He was very informative all through the morning, and he guided the motorman where to take the little Zodiac so that we could see as much as possible.

Click on the thumbnail images below to see some more pictures we took from the Zodiac on our way in (and in one of them you ccan see Nancy and Al Crystal to my left):

|

It took us about fifteen minutes to get from the ship to the point where we slowed down to enter the mangroves.

The Mangroves

|

Mangrove Swamps consist of a variety of salt-tolerant trees and shrubs that thrive in shallow and muddy saltwater or brackish waters. Mangroves can easily be identified by their root system. These roots have been specially adapted to their conditions by extending above the water. Vertical branches, pheumatophores, act as aerating organs filtering the salt out and allowing the leaves to receive fresh water.

Mangroves are thought to have originated in the Far East then over millions of years the plants and seeds floated west across the ocean to the Galapagos Islands. Mangroves live within specific zones in their ecosystem. Depending on the species, they occur along the shoreline, in sheltered bays and in estuaries. Mangroves also vary in height depending on species and environment.

How nature has provided for the spread of the mangrove plant is a marvel of evolution, perhaps no less amazing that the other evolutionary marvels for which the islands are known.

|

Mangroves not only work to transform the landscape, but they provide a home for numerious land and sea creatures- exactly the creatures we have come to see. Click on the thumbnail images below for some of the best of our views of the mangroves here at Elizabeth Bay:

|

Aboard the Zodiac

|

|

To view the slideshow, just click on the image at left and I will open the slideshow in a new window. In the slideshow, you can use the little arrows in the lower corners of each image to move from one to the next, and the index numbers in the upper left of each image will tell you where you are in the series. When you are finished looking at the pictures, just close the popup window.

I made two movies that show our time in the Zodiac- one as we approached the mangroves and another illustrating how our naturalist guide pointed out flora and fauna and described them to us. You can use the players below to watch these movies:

|

Approaching the Mangroves |

Our Naturalist |

Sea Turtles

|

The mature adult Galápagos green turtle is much smaller than those of other Green sea turtle populations; this may be because they are more genetically isolated. The carapace is dark in color, usually black to dark olive-brown, is oval in shape and tapers toward the tail. The carapace has a distinctive formation that is more sloped or domed than individuals of other populations. The largest Galapagos turtles are about three feet long. Their legs are shaped like flippers to aide in swimming; they are broad and generally flattened.

The head is rounded and lizard-like with no teeth and does not have the predominantly hooked beak of many other green sea turtles. The sexes are similar in most aspects except size, the females are slightly larger, and the males have a longer tail.

|

Common food sources for the mature green turtles in the Pacific are marine algae and eelgrasses, but they have been known to consume animal matter as well- although this may not be intentional. It may just be the result of consuming marine algae near the invertebrates. But it may also be intentional so as to provide important nutrients, minerals, or proteins not obtained from vegetation.

We did not see as many turtles as we later discovered were spotted by the earlier Zodiacs. This may have been due to their foraging habits related to the time of day, but we did see two or three of them. Fred and I each took at least one good movie of one of the turtles passing by the Zodiac; you can use the players below to watch these movies:

|

|

|

The green sea turtles that we saw were certainly interesting, and we learned a good deal about them. A bit later on, we'll learn more as we visit a beach where they nest and lay eggs. But for now, we just snapped as many pictures as we could. I've selected the best of them to include here; click on the thumbnail images below to have a look:

|

No sooner had the Zodiac begun to move away from the mangroves that we got the opportunity to see two of the green sea turtles at once, and Fred took the panoramic shot below:

|

Striated Heron

|

Adults have a blue-grey back and wings, white underparts, a black cap, a dark line extends from the bill to under the eye and short yellow legs. Juveniles are browner above and streaked below. These birds stand still at the water's edge and wait to ambush prey, and so are easier to see than many small heron species. They mainly eat small fish, frogs and aquatic insects. They sometimes use bait, dropping a feather or leaf carefully on the water surface and picking fish that come to investigate.

Click on the thumbnail images below to see two more good views of the striated heron:

|

Striated herons nest in a platform of sticks, usually built not too high off the ground in shrubs or trees but sometimes in sheltered locations on the ground, and often near water. The clutch is 2–5 eggs, which are pale blue. An adult bird was once observed in a peculiar and mysterious behavior: while on the nest, it would grab a stick in its bill and make a rapid back-and-forth motion with the head, like a sewing machine's needle. The significance of this behavior is completely unknown. Young birds will give a display when they feel threatened, by stretching out their necks and pointing the bill skywards. The striated heron is not endangered.

Galapagos Penguin

|

While ninety percent of the Galapagos penguins live among the western islands of Fernandina and Isabela, they also occur on Santiago, Bartolomé, northern Santa Cruz, and Floreana. The northern tip of Isabela crosses the equator, meaning that Galápagos penguins occasionally visit the northern hemisphere, the only penguins to do so.

The penguins stay in the archipelago. They stay by the Cromwell Current during the day since it is cooler and return to the land at night. They eat small schooling fish, mainly mullet, sardines, and sometimes crustaceans. They search for food only during the day and normally within a few kilometers of their breeding site. They depend on the cold nutrient-rich currents to bring them food.

The biggest problem for Galapagos penguins is keeping their cool. Their primary means of cooling off is going into the water, but they have other behavioral adaptations because of all the time they spend on land. They use two methods to keep cool on land. First, they stretch out their flippers and hunch forward to keep the sun from shining on their feet- where heat loss is great. They also pant, using evaporation to cool the throat and airways. Galapagos penguins protect their eggs and chicks from the hot sun by keeping them in deep crevices in the rocks.

|

The species is endangered, with an estimated population size of around 1,500 individuals in 2004, according to a survey by the Charles Darwin Research Station. The population underwent an alarming decline of over 70% in the 1980s, but is slowly recovering. It is therefore the rarest penguin species (a status which is often falsely attributed to the yellow-eyed penguin). Population levels are influenced by the effects of the El Niño Southern Oscillation, which reduces the availability of shoaling fish, leading to low reproduction or starvation. However, anthropogenic factors (e.g. oil pollution, fishing by-catch and competition) may be adding to the ongoing demise of this species. On Isabela Island, introduced cats, dogs, and rats attack penguins and destroy their nests. When in the water, they are preyed upon by sharks, fur seals, and sea lions.

There are fewer than 1000 breeding pairs of Galapagos penguins in the world; breeding begins when the sea surface temperature cools to about 75°, and usually occurs between May and January. The Galapagos penguin mates for life. It lays one or two eggs in places such as caves and crevices, protected from direct sunlight. One parent will always stay with the eggs or chicks while the other is absent for several days to feed. The parents usually rear only one child. If there is not enough food available, the nest may be abandoned.

|

Click on the thumbnail images below to see some additional pictures we took of the Galapagos penguins:

|

It was really neat to see the Galapagos penguins, although it would have been better if we had been closer to them. Thank goodness for Fred's excellent zoom!

The Great Blue Heron

|

Their call is a harsh croak. The heron is most vocal during the breeding season, but will call occasionally at any time of the year in territorial disputes or if disturbed. Nonvocal sounds include a loud bill snap, which males use to attract a female or to defend a nest site and which females use in response to bachelor males or within breeding pairs. Bill clappering, the rapid chattering of the tips of the bill, is very common between paired herons.

The great blue heron is found throughout most of North America, as far north as Alaska and the southern Canadian provinces. The range extends south through Florida, Mexico and the Caribbean to South America. Birds east of the Rocky Mountains in the northern part of their range are migratory and winter in Central America or northern South America. From the southern United States southwards, and on the Pacific coast, they are year-round residents. We got quite close to this particular heron, and you can click on the thumbnail images below to see some additional views of it:

|

The great blue heron can adapt to almost any wetland habitat in its range. They may be found in numbers in fresh and saltwater marshes, mangrove swamps, flooded meadows, lake edges, or shorelines. They are quite adaptable and may be seen in heavily developed areas as long as they hold bodies of water bearing fish. Great blue herons rarely venture far from bodies of water but are occasionally seen flying over upland areas. They usually nest in trees or bushes near water's edge, often on islands or other isolated spots.

The primary food for the great blue heron is small fish, though it is also known to opportunistically feed on a wide range of shrimp, crabs, aquatic insects, rodents and other small mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and small birds. Primary prey is variable based on availability and abundance. Herons locate their food by sight and usually swallow it whole. Individuals usually forage while standing in water but will also feed in fields or drop from the air, or a perch, into water. As large wading birds, great blue herons are capable of feeding in deeper waters and thus are able to harvest from niche areas not open to most other heron species. Typically, the great blue heron feeds in shallow waters or at the water's edge.

|

The female lays three to six pale blue eggs, and one brood is raised each year. The first chick to hatch usually becomes more experienced in food handling and aggressive interactions with siblings, and so often grows more quickly than the other chicks. Young are fed by their parents for approximately 100 days, at the end of that time weighing almost 90% as much as an adult. Somewhere between 50-80 days they will take their first flight.

Predators of eggs and nestlings include vultures, ravens, crows, hawks, black bears and raccoons. Adult herons, due to their size, have few natural predators, but a few of the larger avian predators, such as eagles, have been known to kill both young and adults. Since herons spend most of their time in or near water, they are also in danger from alligators and crocodiles (where they exist). Using their considerable size and dagger-like bill, a full-grown heron can be a formidable foe.

We watched this particular bird for a few minutes, expecting it to catch some prey, but it either stood still or just walked slowly along the rocks.

The Galapagos Flightless Cormorant

|

These cormorants evolved on an island habitat that was free of predators. Having no enemies, and taking its food primarily through diving along the food-rich shorelines, the bird eventually became flightless. However, since their discovery by man, the islands have not remained free of predators: cats, dogs, and pigs have been introduced to the islands over the years. In addition, these birds have no fear of humans and can easily be approached and picked up.

The fact that this uniquely adapted bird is found in such a small range and in such small numbers greatly increases its vulnerability to chance events, such as the marine perturbations such as those caused by El Niño events- which are becoming increasingly extreme. Because of these factors, the flightless cormorant is one of the world's rarest birds. Once "endangered", it was downlisted to "vulnerable" in 2011.

We were some distance from the cormorant, so Fred used his zoom lens to take some additional pictures of the bird; in some of the pictures he turned on the "starburst" effect. You can click on the thumbnail images below to see some of these pictures:

|

Nesting tends to take place during the coldest months (July–October), when marine food is at its most abundant and the risk of heat stress to the chicks is decreased. At this time, breeding colonies consisting of around 12 pairs form. The courtship behavior of this species begins in the sea; the male and female swim around each other with their necks bent into a snake-like position. They then move onto land. The bulky seaweed nest, located just above the high-tide mark, is augmented with "gifts" including pieces of flotsam such as rope and bottle caps, which are presented to the female by the male.

The female generally lays three whitish eggs per clutch, though usually only one chick survives. Both male and female share in incubation. Once the eggs have hatched, both parents continue to share responsibilities of feeding and brooding (protecting the chicks from exposure to heat and cold), but once the chicks are old enough to be independent, and if food supplies are plentiful, the female will leave the male to carry out further parenting, and she will leave to find a new mate. Females can breed three times in a single year. Thus, although their population size is small, flightless cormorants can recover fairly quickly from environmental disasters.

The Blue-Footed Booby

|

The blue‑footed booby usually lays one to three eggs at a time. The species practices asynchronous hatching, which means that eggs that are laid first are hatched first, resulting in a growth inequality and size disparity between siblings. This results in facultative siblicide in times of food scarcity, making the blue-footed booby an effective model for studying parent-offspring conflict and sibling rivalry.

Click on the thumbnail images below to see some other good pictures we got of the booby today:

|

The blue-footed booby is about 30 inches long, on average, and weighs just over 3 pounds; the female is slightly larger than the male. Its wings are long and pointed, and are brown in color. The neck and head of the blue-footed booby are light brown with white streaks while the belly and underside exhibit pure white plumage. Its eyes are placed on either side of its bill and oriented towards the front, enabling excellent binocular vision. Its eyes are a distinctive yellow, with the male having more yellow in its irises than the female. Blue-footed booby chicks have black beaks and feet and are clad in a layer of soft white down.

Since the blue-footed booby frequently obtains fish by diving headlong into the water, it has permanently closed nostrils for this purpose, necessitating breathing through the corners of its mouth.

|

|

We'll get some better views of the boobies and their blue feet later, but these feet are so intriguing, we should say more now. Basically, males display their feet in an elaborate mating ritual by lifting their feet up and down while strutting before the female. The brightness of the blue color in an indicator of how healthy the bird is, as it takes significant energy resources to maintain. So birds look for bright feet, and the trait is thus propagated generation after generation. Want to know more? Use the movie player at right to watch an excerpt from the TV series "Nature".

The boobies were the last of the different animals we saw this morning, and we turned to head back to the Xpedition.

Returning to the Xpedition

|

And as we were heading back to the Xpedition ourselves, Fred and I took a few more good pictures of the bay surrounding us and of our group on board. You can click on the thumbnail images below to have a look at some of these:

|

Our First Lunch Aboard the Celebrity Xpedition

|

|

|

To view the slideshow, just click on the image at left and I will open the slideshow in a new window. In the slideshow, you can use the little arrows in the lower corners of each image to move from one to the next, and the index numbers in the upper left of each image will tell you where you are in the series. When you are finished looking at the pictures, just close the popup window.

Galapagos Shore Excursion (4a):

A Short Walk on Isabela

|

| "Tagus Cove is west of Darwin Volcano on Isabela Island and was once a favorite spot for pirates and whalers. At the start of the walk is a small cave where we find inscriptions dating back to the 1800s. Its name originates from a British warship that traveled through the islands in 1814 in search of Galapagos Tortoise for food. The trail is packed sand and gravel and passes by Darwin Lake. Sitting in the crater of a tuff cone, the lake is saltwater and has provoked debate about its formation. Along the path you can see various land birds and characteristic vegetation of the arid zone. The lava fields of Darwin Volcano are visible at a high point at the trail's end.

Dry, but tricky landing. The 2-mile trail has 150 steps, packed sand, gravel, at times narrow and steep |

We left the ship on one of the Zodiacs right about 4:30PM.

Landing at Tagus Cove

|

|

This morning we saw lots of different animals, but this afternoon's hike will be to experience the landscape of Isabela island.

|

|

He also pointed out the little cave where the inscriptions date back more than a century. Then we could get close and look at them ourselves. I took four pictures of the inscriptions, and you can see these pictures if you click on the thumbnail images below:

|

After a short introduction to the hike, we headed off on the trail that led up some steps from the landing area and out onto the island.

Darwin's Lake

|

On the way up, Fred spotted (no pun intended) another lava lizard; they are, apparently, quite common. As we ascended, we had great views of the cove behind us.

After a quick 20-minute climb up the stairs and along the trail, we arrived at the first overlook for Darwin's Lake.

|

The first stop was just east of the lake, so our views were mainly to the west (although we could also see towards the cove). Darwin's Lake is a small lagoon in a crater very near Tagus Cove that is thought to have been formed by a tidal wave when a volcano on Fernandina Island erupted. The lake is a very unusual feature being slightly above sea level and twice as salty as sea water. As water evaporates from the lake, water is replenished from the sea via the porous rocks that separate the sea from the water in the crater. There is a line of salt encrustation along the water's edge of the lake.

Our guide told us that our second stop would be a better vantage point, but we thought this one was nice enough to take a bunch of pictures. But the ones from the second stop were better, so I am only going to include a few of the pictures from this first stop. You can click on the thumbnail images below to have a look at them:

|

The group had headed off ahead of Fred and I, since we were taking pictures, but we eventually followed them a few hundred more feet up the trail, which at this point was right at the edge of the crater. The views from our second stop were indeed more interesting, and I began by letting my little camera take a panoramic view:

Darwin's Lake and Tagus Cove on Isabela Island, Galapagos |

Of course, if you look closely in the cove, you can see the Xpedition anchored a mile or two offshore. We milled about here for ten minutes or so as our guide explained how the lake was formed. I made a movie here, but it really doesn't add anything to the panorama above.

|

To view the slideshow, just click on the image at left and I will open the slideshow in a new window. In the slideshow, you can use the little arrows in the lower corners of each image to move from one to the next, and the index numbers in the upper left of each image will tell you where you are in the series. When you are finished looking at the pictures, just close the popup window.

At the Summit of Our Hike

|

As you might expect, we took a number of pictures from the summit- so many that I've had to boil them down to just those of particular interest. In one, Fred zoomed in on the northern end of Isabela and Cerro Azul; in others, we just tried to show the landscape. You can click on the thumbnail images below to see a few of these pictures:

|

But the only way to do the landscape justice was to view it in panorama. For Fred's part, he used his camera's capabilities to take a native one, including some of the people at the summit to give it scale. That panorama is below:

A Panoramic View from the Summit of Our Hike |

For my part, I wanted to be a bit more ambitious, so I took a series of 9 separate photographs, planning on stitching them together into a single, 360° panoramic view. I almost succeeded; one of my photos was out of line enough to make it look odd when inserted at the end. Sadly, that was the picture above of Fred and I at the summit. But the result was still impressive, I think, and you can use the scrollable window below to have a look at it. When you first see the image, you are looking pretty much due north.

Before I left the summit, I took a few more pictures. I'll never be back here again, so I thought the more the better. I began with a camera-created panorama:

|

I actually had to try that one a number of times; there is a trick to moving the camera steadily while it is snapping pictures.

|

|

The Walk Back

|

Surprisingly, when we got back to the pier, our sea lion friend who had seen us off on our hike was still right where we left him, sound asleep. But as we were getting our lifejackets on, I saw one eye open, and by the time we were ready to board the Zodiac, he was up and flapping around. Below are two pictures and a movie of him:

|

|

|

|

Galapagos Shore Excursion (4b):

A Zodiac Ride Along Isabela Island

Galapagos Flightless Cormorant

|

The flightless cormorant is the largest extant member of its family, 35–40 in. in length and weighing 5.5-11 lbs., and its wings are about one-third the size that would be required for a bird of its proportions to fly. The keel on the breastbone, where birds attach the large muscles needed for flight, is also greatly reduced.

Fred got some really good pictures of the cormorants (using his zoom); if you click on the thumbnail images below, you can see a selection of them:

|

The flightless cormorants look slightly like a duck, except for their short, stubby wings. The upperparts are blackish and the underparts are brown. The long beak is hooked at the tip and the eye is turquoise. Like all members of the cormorant family, all four toes are joined by webbed skin. Males and females are similar in appearance, although males tend to be larger. Juveniles are generally similar to adults but differ in that they are glossy black in colour with a dark eye. Adults produce low growling vocalizations.

Like other cormorants, this bird's feathers are not waterproof, and they spend time after each dive drying their small wings in the sunlight. Their flight and contour feathers are much like those of other cormorants, but their body feathers are much thicker, softer, denser, and more hair-like. They produce very little oil from their preen gland; it is the air trapped in their dense plumage that prevents them from becoming waterlogged.

Blue-Footed Boobies

|

But how, exactly, is it thought that this process worked? First off, it appears that the brightness of the blue color on the feet decreases with age. So, looking at it from the female perspective, they would tend to mate with younger males with brighter feet, who have higher fertility and increased ability to provide paternal care than do older males. In a cross-fostering experiment, it was observed that foot color reflects paternal contribution to raising chicks; chicks raised by foster fathers with brighter feet grew faster than chicks raised by foster males with duller feet.

Females continuously evaluate their partners' condition based on foot color. In one experiment, males whose partners had laid a first egg in the nest had their feet dulled by make-up. The female partners laid smaller second eggs a few days later. As duller feet usually indicate a decrease in health and possibly genetic quality, it is adaptive for these females to decrease their investment in the second egg. The smaller second eggs contained less yolk concentration, which could influence embryo development, hatching success, and subsequent chick growth and survival. The experiment suggested that female blue-footed boobies use the attractiveness and perceived genetic quality of their mates to determine how much resources they should allocate to their eggs. This supports the differential allocation theory, which predicts that parents invest more in the care of their offspring when paired with attractive mates.

Before we look at the male perspective, here are the best of the pictures we took of the blue-footed boobies this afternoon. Just click on the thumbnail images below to have a look:

|

Getting back to the blue feet, it seems that males also assess their partner's reproductive value and adjust their own investment in the brood according to their partner's condition. Females that lay larger and brighter eggs are in better condition and have greater reproductive value. Therefore, males tend to display higher attentiveness and parental care to larger eggs, since those eggs were produced by a female with apparent good genetic quality. Smaller, duller eggs garnered less paternal care. Female foot color is also observed as an indication of perceived female condition. In one experiment, the color of eggs was muted by researchers, it was found that males were willing to exercise similar care for both large eggs and small eggs if his mate had brightly colored feet, whereas males paired with dull-footed females only incubated larger eggs.

Fur Seals

|

|

|

After an interesting, enjoyable and informative Zodiac ride, we went back to the Celebrity Xpedition.

Evening on the Celebrity Xpedition

|

We took some candid pictures while we were relaxing, and you can click on the thumbnail images in the first row below to see some of them. As you can see at left, the sunset was indeed a beautiful one, and we took some additional pictures of it. Click on the thumbnail images in the second row below to see some of those:

|

To conclude our day, I took a series of pictures at sunset that span the view seaward from Tagus Cove and then stitched them together in a long panorama; that panoramic view is below:

|

This brought our second full day in the Galapagos Islands to a close.

You can use the links below to continue to another photo album page.

|

November 12, 2014: Santiago & Bartolome Islands |

|

November 10, 2014: Santiago & Rabida Islands |

|

Return to the Index for Our Galapagos Adventure |