|

June 5, 2012: Home to Dallas |

|

June 3, 2012: Tivoli, Italy: Villa d'Este |

|

Return to the Index for Our Week in Florence and Rome |

Today, Fred, Greg and I are going to see as much as we can of Ancient Rome. We'll begin at the Colosseum, tour the Palatine Hill and the Roman Forum and return to the Pantheon to go inside. Time permitting, we'll visit some other, more modern localse that we haven't yet seen- like the Trevi Fountain. It will be a full day- and our last day in the Eternal City.

|

The area is roughly bounded by the Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II at the northwest, the Circus Maximus on the southwest and the Colosseum on the east.

First, we'll visit the Colosseum, go in, and spend quite a bit of time to see all we can see. Next, we will visit the Arch of Constantine nearby. Then, after a false start to find the entrance, Fred and I will take a complete walk around and through the Palatine Hill, visiting just about every ruin and ancient site there. We'll come down from the Palatine Hill near the Arch of Septimus Severus, which is basically the southeastern end of the Roman Forum.

We'll work our way northwest through the Forum area, which ends just southeast of the huge Vittorio Emanuele Monument. Coming out of the Forum, we will finally go past the Forum of Caesar. (You have already seen some pictures of it, for I walked past it on my way back from the Vatican two days ago, but Fred hasn't yet been to it.)

I'll talk about where our other stops are a bit later on, but now we should start our tour of Ancient Rome.

The Colosseum

|

I know that I like to mark our routes when I use aerial views, but here we were confined to a single structure, and basically to just two or three levels inside it. So having an idea of what level we were on, or how we moved around them or from one to the other is pretty much useless information.

So all you will have is that aerial view, but I think it will give our pictures a great deal of context. I only wish that the day we visited had been as nice as the day on which the aerial photo was taken!

Coming south from the apartment, it wasn't until we got to the Via dei Fori Imperiali, the main avenue that runs diagonally SE to NW along the north side of Ancient Rome, that we had any good views of the Colosseum as we approached, and by then, we were too close to the structure to get it all in one picture. Crossing the street, we found the entrance with no problem and were pleased to find the line to me less than a couple of minutes long. We bought combination tickets to admit us to all of what we wanted to see this morning and went through the turnstiles.

On ground level, there is a vaulted arcade that almost completely encircled the structure. We had to walk a short distance to find the single entrance, went through another turnstile and then through a narrow corridor into the amphitheature.

|

The Colosseum (actually the "Flavian Amphitheatre"), built of concrete and stone, was the largest amphitheatre of the Roman Empire, and is considered one of the greatest works of Roman architecture and engineering. It is the largest amphitheatre in the world. As you can see on the aerial view above, it is situated just east of the Roman Forum. Construction spanned the Emperors of the Flavian dynasty- Vespasian, Titus and Domitian (70-96)- and so was named for them.

The Colosseum seated 50,000 spectators, and was used for gladiatorial contests and public spectacles such as mock sea battles, animal hunts, executions, re-enactments of famous battles, and dramas based on Classical mythology. The building ceased to be used for entertainment in the early medieval era. It was later reused for such purposes as housing, workshops, quarters for a religious order, a fortress, a quarry, and a Christian shrine. Today partially ruined because of damage caused by devastating earthquakes and stone-robbers, the Colosseum is still an iconic symbol of Imperial Rome.

A Short History

|

A Look Around the Colosseum |

By the late 6th century a small church had been built into the structure of the amphitheatre, though this apparently did not confer any particular religious significance on the building as a whole. The arena was converted into a cemetery. The numerous vaulted arcades under the seating were converted into housing and workshops, and are recorded as still being rented out as late as the 12th century. Around 1200 the Frangipani family took over the Colosseum and fortified it, apparently using it as a castle. The great earthquake in 1349 caused the south side to collapse, and much of the tumbled stone was taken and used elsewhere. A religious order inhabited the northern third of the Colosseum from the mid-14th century until the early 19th. The interior stone was stripped for use elsewhere, the marble façade was burned to make quicklime, and the bronze clamps which held the stonework together were pried or hacked out of the walls, leaving numerous pockmarks which still scar the building today.

Promoters, like Pope Sixtus V (1585–1590), looked for a use for the building. Sixtus planned to turn it into a wool factory to provide employment for Rome's prostitutes, and in 1671 Cardinal Altieri authorized its use for bullfights; both ideas were abandoned. In 1749, Pope Benedict XIV endorsed the view that the Colosseum was a sacred site where early Christians had been martyred. He consecrated the building to the Passion of Christ and installed Stations of the Cross, declaring it sanctified by the blood of the Christian martyrs who perished there. There is, however, no historical evidence to support this popular misconception.

|

Because of the ruined state of the interior, it is impractical to use the Colosseum to host large events; only a few hundred spectators can be accommodated in temporary seating, which is usually placed on the wooden stage that has been built at the east end of the arena. However, much larger concerts have been held just outside, using the Colosseum as a backdrop. Performers who have played at the Colosseum in recent years have included Ray Charles, Paul McCartney, Billy Joel, Elton John and, most inspiringly, the group of tenors known as "Il Divo" used it for their performance of "Amazing Grace" in 2009.

From two levels up behind the stage, Fred used his camera's ability to stitch photos together to take this widescreen picture of the interior of the amphitheatre:

Inside the Roman Colosseum |

Architecture: The Exterior

|

In one of the wider corridors, there was a display of column pieces and the various types of pediments that were used in the Colosseum, and you can use the clickable thumbnails below to look at a few pictures of this display:

|

While Cowboy stadium has a retractable roof, the Colosseum had the next best thing. Two hundred and forty mast corbels were positioned around the top of the attic. They supported a retractable awning (velarium) that kept the sun and rain off spectators. It was a canvas-covered, net-like structure made of ropes, and it covered two-thirds of the arena- sloping down towards the center to catch the wind and provide a breeze for the audience. Sailors, specially enlisted from the Roman naval headquarters, were used to work it.

The Colosseum's huge crowd capacity made it essential that the venue could be filled or evacuated quickly, so its architects adopted solutions still used today. The amphitheatre was ringed by eighty entrances at ground level, 76 of which were used by ordinary spectators. Each entrance and exit was numbered, as was each staircase. The northern main entrance was reserved for the Roman Emperor and his aides, whilst the other three axial entrances were most likely used by the elite. All four axial entrances were richly decorated with painted stucco reliefs, of which fragments survive. We found one place where two of these fragments were mounted in approximately the position the were supposed to occupy, so we got up close, took a couple of pictures and put them together for this view:

Decoration from the Entrances to the Colosseum |

|

|

Many of the original outer entrances have disappeared with the collapse of most of the perimeter wall, but along the north and northeast side of the Colosseum, where this tall part of the wall remains, entrances XXIII to LIV still survive. These entrances opened into a vaulted corridor that ringed the building, an arrangement which would seem very familiar today.

You can see many of these levels and how they were built into the exterior structure by looking at one of Fred's pictures here. It was taken as we were leaving the Colosseum, and it looks back at the point on the northwest where the collapse of the outer wall ended; now it makes it appear as if you are looking at a cutaway model.

Architecture: Interior Seating

|

The tier above the senators was occupied by the non-senatorial noble class, and the next level up was originally reserved for ordinary Roman citizens (plebeians) and was divided into two sections. The lower part was for wealthy citizens, while the upper part was for poor citizens. Specific sectors were provided for other social groups: for instance, boys with their tutors, soldiers on leave, foreign dignitaries, scribes, heralds, priests and so on. (There were no areas for gravediggers, actors and former gladiators- they were all banned from entry.)

Stone seating was provided for the citizens and nobles, who presumably would have brought their own cushions with them. Inscriptions identified the areas reserved for specific groups. Another level was added at the very top of the building during the reign of Domitian. This comprised a gallery for the common poor, slaves and women. It would have been either standing room only, or would have had very steep wooden benches. Tiers were divided into sections by low walls, and the occupants of each section used the same entrance/exit. Just as today, each seat could be precisely identified.

I want to include here a couple of large pictures that I made by stitching together bunches of individual pictures. For the first one, I stitched together five pictures that I took panning across a view of the interior of the Colosseum at a single level. That panorama is in the scrollable window below:

The second picture is a composite; it is the combination of sixteen separate pictures, all taken from one end of the arena. You'll notice that not all the picture area is filled in; I was not sure when taking the pictures how many I should take. The sixteen pictures that form this image were taken to try to cover my whole field of view, but I obviously missed some spots:

|

Architecture: The Arena

|

Eighty vertical shafts provided instant access to the arena for caged animals and scenery pieces concealed underneath; larger hinged platforms provided access for elephants and the like. It was restructured on numerous occasions; at least twelve different phases of construction can be seen.

The hypogeum was connected by underground tunnels to a number of points outside the Colosseum. Animals and performers were brought through the tunnel from nearby stables, with the gladiators' barracks at the Ludus Magnus to the east also being connected by tunnels. Separate tunnels were provided for the Emperor and the Vestal Virgins to permit them to enter and exit the Colosseum without needing to pass through the crowds.

Substantial quantities of machinery also existed in the hypogeum. Elevators and pulleys raised and lowered scenery and props, as well as lifting caged animals to the surface for release. There is evidence for the existence of major hydraulic mechanisms and according to ancient accounts, it was possible to flood the arena rapidly, presumably via a connection to a nearby aqueduct.

Taken from above, the pictures of the hypogeum were certainly impressive, but from the lower level, very close to it, they were even more so. But you couldn't get it all in from that position, unless you created a composite shot:

The Hypogeum: A Composite View |

Movies of the Colosseum

|

The Colosseum from the Lower Levels |

The Colosseum from the Cheap Seats |

|

The Colosseum as Seen from the Stage End |

The Colosseum Arena Substructure |

A Final Note

|

To view the slideshow, just click on the image at left and I will open the slideshow in a new window. In the slideshow, you can use the little arrows in the lower corners of each image to move from one to the next, and the index numbers in the upper left of each image will tell you where you are in the series. When you are finished looking at the pictures, just close the popup window.

As we were heading out of the Colosseum, Greg and Fred wanted to stop in the museum store to look around, so I waited outside. When Fred came out, we walked just a few feet away to look out towards the Arch of Constantine- the next thing we wanted to see. I kept an eye out for Greg, although we'd all agreed to leave together. A fair amount of time passed, so I went into the store to look for him, but he wasn't there. We waited a while longer, and then decided to look for him at the entrance or in the plaza out front. He was not anywhere to be found. No one's fault, but we lost each other, and didn't hook up again until late in the afternoon back at the apartment. We ended up seeing many of the same things; just not together.

The Arch of Constantine

To show you where the arch is in relation to the other areas of Ancient Rome we visited today, look at the panoramic view below, taken from the third level of the Colosseum and stitched together out of six separate images. I've marked the sites we'll visit in Ancient Rome today, and you can scroll back and forth across the image to see them.

The arch spans the Via Triumphalis, the way taken by the emperors when they entered the city in triumph. This route led through the Circus Maximus and around the Palatine Hill; immediately after the Arch of Constantine, the procession would turn left and march along the Via Sacra to the Roman Forum and the Capitoline Hill. The arch itself is 70 feet high, 80 feet wide and 25 feet thick. There are three archways, the center one 40 feet high and 20 feet wide, with the lateral archways two-thirds as big. The top (called the "attic") is brickwork faced with marble. There is an inside stairway in the end near the Palatine Hill.

|

Below are clickable thumbnails for some views of Constantine's Arch as we saw it from the Colosseum:

|

The parts of older monuments assume a new meaning in the context of the Constantinian building. As it celebrates the victory of Constantine, the new friezes illustrating his campaign in Italy convey the central meaning: the praise of the emperor, both in battle and in his civilian duties. The other imagery supports this purpose: decoration taken from the "golden times" of the Empire under the 2nd century emperors whose reliefs were re-used places Constantine next to these "good emperors", and the content of the pieces evokes images of the victorious and pious ruler. Historians believe, however, that the real reason for so much re-use was that so little time was available for the completion of the structure.

|

|

The general layout of the main facade is identical on both sides of the arch. It is divided by four columns of Corinthian order made of Numidian yellow marble (giallo antico), one of which has been transferred into the Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano and was replaced by a white marble column. The columns stand on bases showing victory figures on front, and captured barbarians and Roman soldiers on the sides. The spandrels of the main archway are decorated with reliefs depicting victory figures with trophies, those of the smaller archways show river gods. Column bases and spandrel reliefs are from the times of Constantine.

The main piece from the time of Constantine is the "historical" relief frieze running around the monument under the round panels, one strip above each lateral archway and at the small sides of the arch. These reliefs depict scenes from the Italian campaign of Constantine against Maxentius which was the reason for the construction of the monument in the first place. The frieze starts on the western side with the departure from Milan, and continues southward around the arch with the siege of Verona, the Battle of Milvian Bridge, the entrance into Rome, Constantine speaking to the citizens, and Constantine distributing money.

From the Arch of Constantine, we next wanted to walk through the many ruins on the Palatine Hill.

The Ruins on the Palatine Hill

|

Rome has its origins on the Palatine. Indeed, recent excavations show that people have lived there since approximately 1000 BC. Many affluent Romans of the Republican period (c.509 BC – 44 BC) had their residences there. During the Empire (27 BC – 476 AD) several emperors resided there; in fact, the ruins of the palaces of Augustus (27 BC – 14 AD), Tiberius (14 – 37) and Domitian (81 – 96) can still be seen. Augustus also built a temple to Apollo here, beside his own palace.

The entrance to the Palatine Hill was a block or so south of Constantine's Arch, so that's where we headed next. Touring the Hill requires a nominal fee, put towards archaeological efforts.

I wasn't sure how extensive the Hill was, or what we would see, but very soon after we entered and saw our first location map sign, we realized that there was a lot here to see.

|

I'll be breaking up our walk into small sections, each one focused on one or two sites, and we'll begin by turning south from the Palatine Hill entrance to see the Claudian Aqueduct.

The Claudian Aqueduct

|

About seven miles east of this point, the water flowed through a filtering tank and finally out onto arches; these arches increase in height as the ground falls towards the city. We get our detail about the aqueduct from Frontinus in his work published in the latter part of the first century, "De aquaeductu." The aqueduct was, apparently, so sturdy and massive that a short distance from here, in southeast Rome, The church of San Tommaso in Formis was built into its side (in Latin, the aqueduct was the "formia claudia").

The picture at left shows a section of the aqueduct just as it comes onto the slope of the Palatine Hill, and it is constructed of Roman brick (restoration has been done). The Aqua Claudia maintained its structure and appearance for so long because of the ingredients inside the concrete. Romans would mix in volcanic ash which made the concrete stronger and durable. In some other sections, the aqueduct was either constructed of or supported by stone arches, like the one just west of the brick portion we saw. These sections have not fared nearly so well over time.

The aqueduct was powered by gravity; it drops at a constant rate of 1 foot for every 300 linear feet. As mentioned, much of the aqueduct was underground, but some was at ground level and about 7 miles carried on arches which, at their highest point, were over 100 feet high. The path we were following actually took us right through the aqueduct, between the brick and stone portions.

The Domus Severiana

|

Part of Severus' complex were an extension of the imperial baths, the remains of which are also visible today. These baths were fed with water from the Claudian Aqueduct; Severus had a junction to the aqueduct built to bring water to his own palace, the supports of this spur aqueduct can still be seen. On the side facing the Via Appia Septimius Severus did build an impressive façade like a theater scene, with fountains and colonnades on three levels; it was called the Septizonium. Sadly, the remains of that splendid building were demolished in the sixteenth century and it is known today only from Renaissance drawings that have survived.

|

Before we headed up the path to the top of the Palatine Hill, Fred took some additional pictures of the ruins of the palace of Septimus Severus from a different viewpoint, and you can use the clickable thumbnails below to have a look at some of them:

|

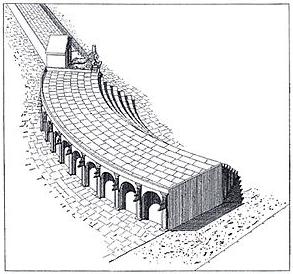

The Flavian Stadium

|

The magnificent sculptures found here (now in the Palatine Museum) show that the area was decked out as an art gallery. On one of the long sides was an exedra with a view of the entire garden. At each end there was a semicircular fountain veneered in marble, with an open space at the center decorated with multiple statues. The fountains are long gone; what is in the semi-circular spaces now is Verbena. This plant has been known since antiquity, and was considered by th eRomans to have medical properties and magical powers. In his writings, Pliny described two species- "officinalis" and "supine".

Below are clickable thumbnails for some additional views of the Flavian garden:

|

The presence of channels that carried water to the center of the "stadium" and the absence of any kind of pavement provide additional evidence that this area was a garden. The purpose of the oval area at the south end is not known, although one presumes that it was to delineate that particular area of the garden. Also, at the two northern corners, there were rooms below grade. These might have been for storage, or used by the gardeners, but it appears that the outside track, used for pedestrians, carriages and litters, went through sheltered overhangs at these two corners.

Below are clickable thumbnails for some additional pictures taken near the Flavian "stadium":

|

The Domus Augustana

|

|

The upper level contained public spaces such as reception and banquet halls. The lower level was devoted to the private quarters of the imperial family. Facing the south was a gently curved facade visible from the Circus Maximus in the valley below. (Although we did not visit the Circus Maximus to see that view of the Domus Augustana, if you have been following us on the aerial view you can see the remains of that curved facade.) There were points where we could look across the ruins of the Domus Augustana and through an opening to the Circus Maximus. (You can see that opening on the aerial view.) To the east are the two sites we just visited- the Flavian Stadium (also known as the Hippodrome), the enormous sunken garden in the form of a race track, and the Severan extension, the additional palace area built by Septimus Severus.

From the Severan extension, we were walking across the top of the Palatine Hill. Nearest us on our path was an area of the Domus Augustana called the lower peristyle. It was lavishly decorated and had at its center, as usual, a grand fountain. The fountain's most distinctive feature was its pattern of four "peltae" (crescent-shaped chields, as used by Amazons) separated by semi-circular channels. You can see here the remains of that fountain (planted with verbena).

The original height of the shields and of the fountain is uncertain, but it was probably ten or fifteen feet. We should probably imagine it with a very high jet of water at the center. The area was also decorated with abundant flowerbeds, small basins that held ornamental fish, and many sculptures. This distinctive stage set-like arrangement of water and architecture was surely inspired by some of the structures of Hadrian's Villa.

The open area was surrounded by numeroud living rooms and nymphaea, which would have made it a particularly cool part of the palace on hot days.

The Museo Palatino

|

|

The museum was set up in the convent built in 1868 by the nouns of the Visitation; by 1920 it was no longer being used. The building was completely updated in the 1960s, and now artifacts dating from prehistory to the fourth century AD are displayed. There are clickable thumbnails below so you can see more of these items:

|

Augustus put his private home here on the Palatine Hill (we will tour it a bit later), and he also erected the Temple of Vesta and the imposing Temple of Apollo.

|

The Palatine Hill was very fertile ground for the discovery of a wide range of artifacts, for in addition to being the residence of a number of Emperors, under the reign of Tiberio the building of the magnificent palace on the hill was begun; this palace would become the imperial residence- much like our White House, or perhaps more like Buckingham Palace. As you have already seen, it was a large complex that comprised residential areas with peristiles, gardens and wide representation halls. The Imperial Palace was finally completed under the reign of Domiziano, and consisted of the domus Flavia, the domus Augustana, the stadium and the thermal baths.

The Flavian Palace

|

The Flavian Palace contained several large rooms and suites of rooms; only the outlines or some ruined walls of these rooms remain. The main rooms were the Basilica, the Aula Regia, the Lararium, and the Triclinium. The Basilica was a group of three rooms and was the first part of the palace visible when one came here from the Forum. South of that would have been the Aula Regia, one of the biggest rooms in the palace. In the time of Domitian, the walls had a marble veneer, and there were Phrygian marble columns and an elaborately carved frieze. It was a room where large state functions would be held.

The third room, the Lararium, was the smallest room of the group, and its purpose may have varied. Behind it was once a staircase providing access to the Domus Augustana. There were also a peristyle and suites of rooms to the west and east of these three rooms. The Triclinium is the last major room in the palace. Like the Aula Regia, it was large and extravagantly decorated, with Corinthian columns and a frieze. It opened on two courtyards with fountains to the north and south.

The poet Statius, a contemporary of Domitian, had this to say about the palace: "Awesome and vast is the edifice, distinguished not by a hundred columns but by as many as could shoulder the gods and the sky if Atlas were let off. The Thunderer’s palace next door gapes at it and the gods rejoice that you are lodged in a like abode. So great extends the structure and the sweep of the far-flung hall, more expansive than that of an open plain."

|

The Flavian Palace was one of Domitian’s many architectural projects, which also included the Domus Augustana, a contribution to the Circus Maximus, a contribution to the Pantheon, and three temples deifying his family members: the temple of Vespasian and Titus, the Porticus Diuorum, and the Temple of the gens Flavia.

Below are clickable thumbnails for some other views of the Flavian Palace and the octagonal fountain:

|

The Farnese Lodge

|

The Farnese expanded their influence in Tuscany when, in 1319, they acquired Farnese along with other castles and holdings. They continue to support the Papacy militarily and in 1368, Niccolò Farnese saved Pope Urban V from attack. As a result, the family was granted confirmation of their possessions and given privileges that raised them to the top echelon of powerful Italian families.

The family substantially increased its power in the course of the 15th century, and the family commanded the forces of Siena against the Orsini. Pier Luigi Farnese married a member of the ancient baronial family of the Caetani (that of Pope Boniface VIII), thus giving the Farnese further importance in Rome. He was to be outdone, however.

His daughter, Giulia, became a mistress of Pope Alexander VI, and it was she who further expanded the Roman fortunes of her family by persuading the Pope to bestow on her brother Alessandro, the title of cardinal. He did so and a short time later, in 1534, Alessandro was himself elected as pope and took the name of Paul III. It was during Alessandro's cardinalship that he aquired some vineyards and land on the Palatine Hill.

|

The House of Augustus

After defeating Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium (27 BC), Octavian returned to Rome in triumph. He was awarded a number of titles by the Roman Senate, one of which was "tribune of the people." This cemented his popular image as a citizen first and leader second, but he was, in effect, already the first Roman Emperor. By 23 BC, he had solidified his power and embarked on his expansion of the Empire. In that year, Caesar Augustus decided to buy the house of Quintus Hortensius on the Palatine and make it his primary place of residence.

|

The Domus Augusti was located near the sacred sites which related to the foundation of Rome. The residence contained two levels, each leading to a garden courtyard. The bottom floor is not accessible today, but it is possible to make out the basin of a fountain and the rooms beyond it that were paved in coloured marble.

According to historians, the house burned, perhaps in 3 AD, but was then rebuilt and made the property of the state. Suetonius (69-122) speaks of it in the past tense, so it may be presumed that it burned again during the fire of Nero. It was rebuilt and reused several times in the first and second centuries before falling into disuse as a residence.

The house today is an active archaeological site, and has been covered by a modern roof structure so as to impede further deterioration. Excavations are ongoing, and visitors, such as ourselves, often see people at work. There are areas under roof set aside for fragments that are unearthed, and access to the house is tightly controlled. We had to cross just south of the site of the house of Livia (Augustus' wife) to find the entrance to the ruin of the house. It was here that a peristyle and garden were located. A sign said that for the purposes of exhibition, this area is being used for a real-life reconstruction of the garden. That reconstruction is based on wall paintings in the villa of Livia, just north of the Augustus' house.

|

|

When the last member of the group before ours had come out, we were ushered in for a fifteen-minute visit.

The house of Augustus was adjacent to the Temple of Apollo, built about six years before Augustus purchased the property, and it was linked structurally to that temple; access to the temple was from the eastern side of the house through a portico. Another portico, still to be excavated in its entirety, opened onto the libraries, still only partly excavated. The libraries were destroyed during the fire under Nero and were reconstructed by Domitian. Archaeological investigations continue, and will perhaps settle some of the heated academic debates over aspects of the construction of the building and the uses to which it was put over the years.

The house had a complex architectural structure. To its original nucleus, composed of the house of the orator Hortensius, other dwellings were subsequently added. The rooms excavated to date backed up against the hillside. There was a private zone, which visitors cannot see, and a public area that is accessible. It had coffered ceilings with elaborate stuccco decorations. The house is the most important complex of "Second Style" paintings found in Rome in recent decades, although parts of the paintings are missing and parts are recomposed. We also got to peek into the nymphanaeum, probably the oldest part of the house.

We were able to look into the carefully restored upper cubiculum room which has the finest and most elegant decorations. The vivid colors of its paintings, only recently replaced in situ, and the originality and refinement of their decorative syntax, create an extraordinary effect.

|

|

When our visit time was up, we headed off to see more of the Palatine Hill.

The House of Livia

|

Shortly afterward, the house probably became part of the ambitious building project whose goal was to create space for the large new house built by Augustus after 31 BC. The house was entered via a corridor with a ramp; this led into a square courtyard flanked by three rooms. There was an atrium and servants quarters as well. The identification of this structure as the house of Livia, the wife of Augustus, is based from the fact that a number of lead pipes with the name "Iulia Augustus" inscribed on them have been found. There is no certain proof, however, of her actual presence in the residence. The hypothesis is that she lived here during her first marriage to Tiberius Claudius Nero, which was dissolved to allow her to marry the young Octavian in 38 BC. If that is the case, then this house was the birthplace of the future emperor Tiberius.

The Neronian Cryptoporticus

|

To get to it, we went north from the House of Livia, and then alongside an arched wall- which turned out to be part of an old aqueduct. At the east end, we found a narrow corridor between two buildings that led to a set of stairs down into the cryptoporticus. Originally, the vault was covered with fine white stucco, depicting cupids within decorative frames. Only a few fragments remain. While this stucco decoration has generally been dated to the age of Nero, it probably relates to an earlier period, the first half of the first century AD.

We were somewhat surprised in the long corridor that there were exhibits set up near the middle, and we spent some time looking at them. I couldn't quite spot the windows that are usually up in the vault of one of these structures, and there might not have been any. But on the walls there were projections that seemed to come from lightboxes high on the opposite wall. It was interesting and, other than the fact that it was a sheltered place for the exhibits and that the projections lighted what would otherwise have been a long, dark corridor I wasn't sure why either the exhibits or the projections were here. Fred took pictures of each of the projections and one of the exhibits, and you can use the clickable thumbnails below to have a look at them:

|

Views from the Palatine Hill

|

Rome Seen from the Palatine Hill |

I've put clickable thumbnails below for some of the pictures of Rome we took from here:

|

From the overlook, we wandered along the paths back to the northeast towards the gardens.

Domus Tiberiana

|

At the garden level, excavation has revealed the remains of a colonnaded portico and, within the peristyle, a large, multi-lobed basin, covered with white marble slabs. This basin shows signs of rebuilding several times during the Imperial period, but its original construction ties in with the presence of a lead water pipe inscribed with the name of the Emperor Claudius.

This provides unexpected by important evidence that it was not Nero who transformed the Domus Tiberiana into a monumental palace, but the elderly Claudius (Emperor from 41 to 54), perhaps drawing on an existing project of Tiberius and Caligula. Claudius was the learned Emperor married first to Messalina, who was killed for her infidelities, and then to his niece Agrippina, whose son, Nero, he adopted.

It was in this palace (as Suetonius relates) that Nero was made Emperor at the age of 17, and here that he lived under the enlightened influence of Seneca, in the early years of his reign.

The porticoes, gardens and basins discovered in the Gardens were replaced by a complex system of cryptoporticuses, rooms and underground corridors that served to connect the different nuclei of the Imperial Palace. The foundations of these galleries have suffered serious subsidence and the consequernt collapse of several walls. The excavations (no longer visible today) that took place here hae revealed the height of the vaulted structures (about 16 feet) and their plan.

The cryptoporticuses were arranged to form a wide quadrilateral illuminated by basement lights; to their sides were rooms of different dimensions, stairways and corridors that reflect at least two chronological phases, of the Augustan to Neronian periods. In fact, this underground section of the Julio-Claudian palace had a limited life and seems to have been abandoned by the Flavians.

It is likely that these were the galleries where, according to Flavius Josephus, the Emperor Caligula was assassinated by conspirators led by Cassius Chaerea. Among the many precious pieces of sculpture recovered in the excavations there were splendid wings, perhap sbelonging to a Victory, and the headless male statue in Greek marble, with traces of color on his clothes, on display in the Palatine Museum. Many architectural and sculptural fragments were also found, including a beautiful portrait of an empress- possibly Faustina Minor. Near the Farnese Gardens, excavations are still ongoing.

The Farnese Gardens

|

The site overlooks the Roman Forum and is near the Arch of Titus. He called this Horti Farnesiani (possibly meaning to suggest the hortus conclusus or "enclosed garden" where Mary conceived Jesus Christ). The garden was divided into the classic style of quadrants with a well or a fountain at its center.

The Farnese family died out with Elizabeth, who married Philip V of Bourbon. The gardens were rented out and became a farm. Cypresses, laurels and holm oaks were replaced by vines and artichokes. The Farnese legacy lives on, however; the family has lent its name to the plant "Acacia farnesiana" and from its floral essence, the important biochemical farnesol.

The only remnants left from the actual Farnese gardens are what archaeologists and historians believe are some of the original stone garden ornaments.

The gardens we see today are not the original gardens; those disappeared in the early 1700s. What we see today is actually called The Boni Gardens. At the start of the 20th century, the archaeological excavations directed by Giacomo Boni under the patronage of Francesco Crispi drew to an end. Boni himself undertook the arrangement of the remaining part of the Farnese Gardens where he restored beds bordered by box hedges. Subsequently, he, himself, was buried there.

The Farnese Palace

|

Little of the original structure survives today, although some of it has been incorporated into more recent structures. There is now a small chapel here, and one can still visit the overlooks for views of the Forum. From here, outside stairs lead down to the exit from the Palatine Hill and to the Arch of Titus- pretty much the beginning of the walk northwest through the Roman Forum.

Below are clickable thumbnails for the last of the pictures we took at the Farnese Palace and coming down from the Palatine Hill:

|

If you have been using the aerial view to follow along with us on our walk across the Palatine Hill, and if that window is still open, you can close it now.

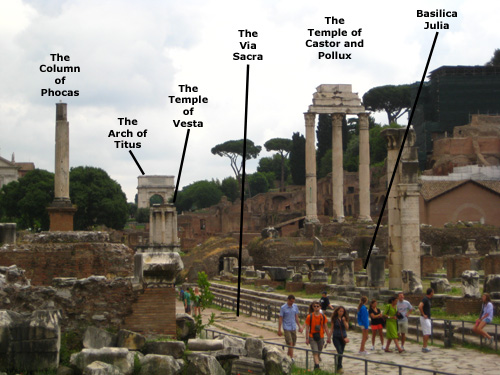

A Walk Through the Roman Forum

|

It was for centuries the center of Roman public life: the site of triumphal processions and elections; the venue for public speeches, criminal trials, and gladiatorial matches; and the nucleus of commercial affairs. Here statues and monuments commemorated the city's great men. The teeming heart of ancient Rome, it has been called the most celebrated meeting place in the world in all history. Located in the small valley between the Palatine and Capitoline Hills, the Forum today is a sprawling ruin of architectural fragments and intermittent archeological excavations.

Many of the oldest and most important structures of the ancient city were located on or near the Forum. The Roman kingdom's earliest shrines and temples were located on the southeastern edge. Other archaic shrines to the northwest developed into the Republic's formal assembly area. This is where the Senate— as well as Republican government itself— began. The Senate House, government offices, tribunals, temples, memorials and statues gradually occupied the area.

Over time that archaic space was replaced by the larger adjacent Forum and the focus of judicial activity moved here, a process that culminated under Julius Caesar. This new Forum, in what proved to be its final form, then served as a revitalized city square where the people of Rome could gather for commercial, political, judicial and religious pursuits in ever greater numbers.

Eventually much economic and judicial business would transfer away from the Forum Romanum to the larger and more extravagant structures (Trajan's Forum and the Basilica Ulpia) to the north. The reign of Constantine the Great, during which the Empire was divided into its Eastern and Western halves, saw the construction of the last major expansion of the Forum complex, which returned the political center of the Western Empire to the Forum until its fall almost two centuries later.

So much history and so much majesty in such a small space. We covered the area in a couple of hours, wishing all the while that we could turn back time and see it whole and functioning.

|

I hope you find the aerial view interesting; when we have finished our walk through the remains of the ancient Forum and are ready to head off to our next stop, I'll remind you so that you can close the window. And, as I did on the Palatine Hill, I break up the narrative and pictures into sections- one for each major point of interest. So let's go to the end of the Via Sacra nearest the Arch of Constantine and begin.

The Via Sacra

|

The road provided the setting for many deeds and misdeeds of Rome's history, the solemn religious festivals, the magnificent triumphs of victorious generals, and the daily throng assembling in the Basilicas to chat, throw dice, engage in business, or secure justice. Many prostitutes lined the street as well, looking for potential customers.

The picture at left was taken at the exit from the Palatine Hill where we could look west and see, over a rise, the main part of the Roman Forum. When we came through the area of ruins currently being excavated, we were in the middle of the Via Sacra. Looking towards the Colosseum, the Palatine Hill ruins are on our right, and the ruins of the Temple of Venus and Rome were on our left (north), just past the colonnade. Looking in the other direction (west) we could see the Arch of Titus that we'll be heading to in a little while.

Excavations Along the Palatine Hill

|

Looking at this excavation from the present-day Via Sacra, one is facing the long rear wall of the Neronian-Flavian portico that ran along the street leading from the Colosseum to the Roman Forum. On the south side of that portico were the vaulted spaces that supported the Neronian terrace, and the structures that continue along the hillside to the Forum.

The Temple of Venus and Rome

From our position on the Via Sacra, we were looking up at the hill on which the temple was situated, and we couldn't see much except the columns in front of us. Earlier, when we were on the third level of the Colosseum, we took pictures looking down, and these showed the extent of the temple much better. Sadly, the weather was bad just then, and our pictures were quite dark. So instead of one of those, I have used a stock shot taken from exactly the spot we were standing- but on a much nicer day. In that photo (seen below) we are standing in the street to the left of the row of columns at left in the picture.

|

The temple was 476 feet long, 328 feet wide, and 100 feet high. The temple itself consisted of two main chambers (cellae), each housing a cult statue of a god— Venus, the goddess of love, and Roma, the goddess of Rome- both figures seated on a throne. The cellae were arranged symmetrically back-to-back. Roma's cella faced west, looking out over the Forum Romanum, and Venus' cella faced east, looking out over the Colosseum. A row of four columns (tetrastyle) lined the entrance to each cella, and the temple was bordered by colonnaded entrances ending in staircases that led down to the Colosseum.

The west and east sides of the temple (the short sides) had ten white columns (decastyle), and the south and north (the long sides) featured eighteen white columns. All of these columns measured 1.8 metres (6 ft) in width, making the temple very imposing. While we cannot be sure, a reconstruction of the temple interior by a German architect in 1913 depicts two longitudinal colonnades of Corinthian columns forming a central nave flanked by two aisles below a coffered vaulted ceiling.

The Basilica of Santa Francesca Romana

|

The interior is a single nave with side chapels, and was rebuilt in 1595. It has an ornate confessional, done in polychrome marbles with four columns veneered in jasper. The church houses the precious Madonna Glycophilousa ("our Lady of the tenderness"), an early 5th century Hodegetria icon brought from Santa Maria Antiqua. The twelfth-century Madonna and Child that had been painted over it was meticulously detached in 1950 from the panel and is now kept in the sacristy. The tomb of Pope Gregory XI, who returned the papacy to Rome from Avignon, is in the south transept.

Saint Francesca Romana being the patron of car drivers, automobiles are lined up on the day of her feast (9 March) as far as the Colosseum, to partake of a blessing.

The Arch of Titus

|

|

The deeply‑coffered archway has a relief of the apotheosis of Titus at the center. The sculptural program also includes two panel reliefs lining the passageway within the arch. Both commemorate the joint triumph celebrated by Titus and his father Vespasian in the summer of 71.

The south panel depicts the spoils taken from the Temple in Jerusalem. The Golden Candelabra or Menorah is the main focus and is carved in deep relief. These spoils were originally gilded with gold, with the background in blue. The north panel depicts Titus as triumphator attended by various genii and lictors, who carry fasces. A helmeted Amazonian, Valour, leads the four-horsed chariot, which carries Titus. Winged Victory crowns him with a laurel wreath. The juxtaposition is significant in that it is one of the first examples of divinities and humans being present in one scene together.

The inscription in Roman square capitals reads: "The Roman Senate and People (dedicate this) to the divine Titus Vespasianus Augustus, son of the divine Vespasian." On the opposite site, the Arch received new inscriptions after it was restored during the pontificate of Pope Pius VII in 1821; travertine was used to differentiate between the original and the restored portions. The new inscription reads: "(This) monument, remarkable in terms of both religion and art, had weakened from age: Pius the Seventh, Supreme Pontiff, by new works on the model of the ancient exemplar ordered it reinforced and preserved. In the year of his sacred rulership the 24th".

We walked through the arch to the northwest side of the arch, down some stairs and on towards the Roman Forum ahead of us.

The Basilica of Maxentius

|

Running the length of the eastern face of the building was a projecting arcade. On the south face was a projecting porch with four columns; you can see that porch in the picture at left, and Fred took a nice picture of me standing in front of it- a picture that you can see here.

The south and central sections were probably destroyed by the earthquake of 847. All that remains of the basilica is the north aisle with its three concrete barrel vaults. The ceilings of the barrel vaults show advanced weight-saving structural skill with octagonal ceiling coffers. Basilicas served a variety of functions, including that of a court-house, council chamber and meeting hall. There might be numerous statues of the gods displayed in niches set into the walls- much as our public buildings have statues or portraits of national or local politicians. Under Constantine and his successors this type of building was chosen as the basis for the design of the larger places of Christian worship, presumably as the basilica form had fewer pagan associations and allowed for large congregations. As a result of the building programmes of the Christian Roman emperors the term basilica later became largely synonymous with a large church or cathedral.

The Basilica of Maxentius is a marvel of Roman engineering work. At the time of construction, it was the largest structure to be built and thus is a unique building taking both aspects from Roman baths as well as typical Roman basilicas. At that time, it used the most advanced engineering techniques known including innovations taken from the Markets of Trajan and the Baths of Diocletian.

Back out on the Via Sacra by the north end of the Basilica of Maxentius, we had a good view of not only the excavations along the Palatine Hill, but the way ahead towards the Forum. I took this opportunity to make a panorama out of five separate pictures. You can have a look at that panorama below:

|

More Excavations Along the Palatine Hill

|

Between the 1st century BC and the 1st century AD, the area was the site of a rich dwelling adorned with mosaics and frescoed walls. octagonal ceiling coffers stood along this dwelling's street-front. It is possible that Octavian, the future emperor Augustus, was born in this house in 63 BC. The house was in use until 64 AD, when the fire of Nero destroyed a large part of the city, and thereby allowed the emperor to transform the whole area into a monumental entryway for his residence upon the Palatine. Between the House of the Vestals and the Basilica Julia, were some stairs leading up into these buildings.

Just a short ways past the Basilica of Maxentius, there was a path that led across the Via Sacra and over to these hillside ruins, and we decided to go over and have a look. Midway across the little valley, Fred stopped to make a panoramic view of the Forum to the northwest, and you can see that view below:

|

We spent a few minutes over by the Palatine excavations before returning to the Via Sacra to head closer to the Forum itself. At various times in the next hour we came near the excavations again. I've collected together the best of the pictures we took of the ruins that run from the Forum to the Arch of Titus, and have put clickable thumbnails for them below:

|

The Temple of Antoninus and Faustina

|

|

But when I looked up the Temple for this narrative, and saw a picture of it, I discovered that the actual Temple was the building just west of this one- the building that has the construction fabric draped on its front. That fabric hides the row of columns that form the front of the Temple. In fact, you can see columns behind the fabric if you look closely at the picture.

Even if we had known which building was the Temple, it wouldn't have done much good, for the impressive facade was hidden behind the frabic draped in front of it. So what would the temple have looked like had it not been under renovation?

|

The temple was begun in 141 AD by the Emperor Antoninus Pius and was initially dedicated to his deceased and deified wife, Faustina the Elder. When Antoninus Pius was deified after his death in 161 AD, the temple was re-dedicated jointly to Antoninus and Faustina at the instigation of his successor, Marcus Aurelius. The building stands on a high platform of large granite blocks, and the inscription on the attic translates as: “To the divine Antoninus and to the divine Faustina by decree of the Senate.”

The ten monolithic Corinthian columns of its pronaos are 55 feet tall. There are rich bas-reliefs on a frieze under the cornice, featuring garlanded griffons and candelabri. The temple was converted to a Roman Catholic church, known as San Lorenzo in Miranda, perhaps as early as the seventh century. Side chapels were added to the structure sometime after 1429.

In 1536, the church was partially demolished, and the side chapels removed, in order to restore the ancient temple for the Roman visit of Emperor Charles V. The church, now constrained within the cella of the temple, was redesigned in 1602, creating a single nave and three new side chapels. Christianization has accounted for the survival of the cella and portico of the temple, though the marble cladding of the cella has been scavenged. Indeed, the church lacks the usual east-end apse: one was never added, to retain the temple's structural integrity.

The Temple of Vesta

|

All temples to Vesta were round, and had entrances facing east to symbolize the connection between Vesta’s fire and the sun as sources of life. The Temple of Vesta represents the site of ancient cult activity as far back as 7th century BC. Numa Pompilius is believed to have built this temple along with the House of the Vestal Virgins in its original form. Below are clickable thumbnails for three more views of the temple:

|

This was one of the earliest structures located in the Roman Forum, although its present incarnation is the result of subsequent rebuilding. Instead of a cult statue in the cella there was a hearth which held the sacred flame. The temple was the storehouse for the legal wills and documents of Roman Senators and sacred objects such as the Palladium (a statue of Athena/Minerva believed to have been brought by Aeneas from Troy and believed to be one of the pledges of imperium of Ancient Rome). According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, the Romans believed that the Sacred fire of Vesta was closely tied to the fortunes of the city and viewed its extinction as a portent of disaster.

Although there was a fire in the temple, it did not pose a great risk to burning down since the fire was maintained in a hearth and watched closely by the Vestals. But twice in its history, the temple was destroyed by fires that began elsewhere in the forum. The first, in 64, was the Great Fire of Rome (Nero's fire). The other was a fire in 191, after which the wife of Septimius Severus had the temple restored. The sacred flame was put out in 394 by Theodosius I after he won the Battle of the Frigidus, defeating Eugenius and Arbogast. The temple has been looted and was stripped of its marble during the 16th century. The section standing today was reconstructed in the 1930s during the dictatorship of Benito Mussolini.

The House of the Vestal Virgins

|

Below are clickable thumbnails for some of the pictures we took of the statuary in the Atrium:

|

The complex lay at the foot of the Palatine Hill, where a sacred grove that was slowly encroached upon lingered into Imperial times. Before the fire in the reign of Nero, the House of the Vestals had a different shape, size and orientation. The oldest surviving structure dates to the 6th century BC; it was then rebuilt from tuff blocks in the 3rd century BC, and redesigned in the late Republic-early Empire. Recent excavations have revealed a hut dating to the mid-8th century BC. This may have been the earliest home of the priestesses.

|

|

Here, beneath the imperial paving with its chambers for the heating system, the remains of walls and mosaics of the Republican H ouse of the Vestals were found. The House of the Vestals was rebuilt several times in the course of the Empire. Below are clickable thumbnails for some pictures we took of the ruins of the House of the Vestals, and there are also, intermixed with them, ruins of later constructions through the 3rd century:

|

The Temple of Castor and Pollux

|

In Republican times the temple served as a meeting place for the Roman Senate, and from the middle of the 2nd century BC the front of the podium served as a speaker's platform. During the imperial period the temple was a depository for the State treasury. The archaic temple was completely reconstructed and enlarged in 117 BC by Lucius Caecilius Metellus Dalmaticus after his victory over the Dalmatians; another restoration was carried out in 73 BC.

In 14 BC a fire that ravaged major parts of the forum destroyed the temple, and Tiberius, the son of Augustus by a previous marriage of Livia and the eventual heir to the throne, rebuilt it. Tiberius' temple was dedicated in 6 AD. The remains visible today are from the temple of Tiberius, except the podium, which is from the time of Metellus. According to Gibbon, the Temple was the meeting place at which the Senate was roused to rebellion against the Emperor Thrax in 237.

The temple was still standing intact in the 4th century, but nothing is known of its subsequent history, except that in the 15th century, only three columns of its original thirty-eight were still standing. Today the podium, a raised area (25 feet high) accessed via a set of central stairs, survives without the facing, as do the three columns and a piece of the entablature, and it is one of the most famous features in the Forum. From the area to the west of the Temple of Vesta, I got what I thought was a very good picture of Fred and both the Temples of Vesta and of Castor and Pollux, and you can see that picture here.

|

|

So I tried my hand at getting relatively close to the ruin and then photographing it in sections; this has worked before on this trip, and I hoped it would work well now. It did, but apparently I was not as good in aligning the three pictures I took so that they would stitch together well. I did get three pictures, and I was able to stitch them together, but you'll be able to see some anomalies in that the columns are a bit warped.

Even so, I think that looking at the ruin close up is interesting, and I have put this composite picture in the scrollable window at right.

Basilica Julia

|

The building burned shortly after its completion, but was repaired and rededicated in 12 AD. The Basilica was again reconstructed by the Emperor Diocletian after the fire of 283 AD. The Basilica housed the civil law courts and tabernae (shops), and provided space for government offices and banking. In the 1st century, it also was used for sessions of the Centumviri (Court of the Hundred), who presided over matters of inheritance. In his Epistles, Pliny the Younger describes the scene as he pleaded for a senatorial lady whose 80-year-old father had disinherited her ten days after taking a new wife.

Below are clickable thumbnails for three additional pictures showing the Basilica Julia from the Via Sacra:

|

The Basilica Julia was the favorite meeting place of the Roman people. On the pavement of the portico, there are diagrams of games scratched into the white marble. One stone, on the upper tier of the side facing the Curia, is marked with an eight by eight square grid on which games similar to chess or checkers could have been played. All around the large area that was occupied by the basilica, there are marble column fragments that have been set back on pedestals. These may or may not be parts of original columns, but are certainly not the fragments from the particular column in that position.

|

The building consists now only of a rectangular area, levelled off and raised about one metre above ground level, with jumbled blocks of stone lying within its area. A row of marble steps runs full length along the side of the basilica facing the Via Sacra, and there is also access from a taller flight of steps (the ground being lower here) at the end of the basilica facing the Temple of Castor and Pollux.

The site was excavated by Pietro Rosa in 1850 who reconstructed a single marble column and travertine supports. In 1852 segments of concrete vaulting with stuccowork coffering was unearthed but later destroyed in 1872. In the picture of the reconstructed column, the flaring at the top is the beginning of arches for the bottom tier.

The Column of Phocas

|

| To the best, most clement and pious ruler, our lord Phocas the perpetual emperor, crowned by God, the forever august triumphator, did Smaragdus, former praepositus sacri palatii and patricius and Exarch of Italy, devoted to His Clemency for the innumerable benefactions of His Piousness and for the peace acquired for Italy and its freedom preserved, this statue of His Majesty, blinking from the splendor of gold here on this tallest column for his eternal glory erect and dedicate, on the first day of the month of August, in the eleventh indiction in the fifth year after the consulate of His Piousness. |

The precise occasion for this signal honour is unknown, though Phocas had formally donated the Pantheon to Pope Boniface IV. Atop the column's there was a gilded statue of Phocas (which probably only briefly stood there). Rather than a demonstration to mark papal gratitude as it is sometimes casually declared to be, the gilded statue on its column was more likely an emblem of the imperial sovereignty over Rome, which was rapidly fading under pressure from the Lombards, and a personal mark of gratitude from Smaragdus, who had been recalled by Phocas from a long exile and was indebted to the Emperor for retrieving his position of power at Ravenna.

In a perfect example of "all glory is fleeting," in October 610, Phocas, a low-born usurper himself, was assassinated, and all his statues everywhere were overthrown.

The monument remains today in its original location. Its isolated, free-standing position among the ruins has always made it a landmark in the Forum, and it often appears in engravings. The rise in ground level due to silt and debris had completely buried the base by the mid-18th century. The square foundation of brick was not originally visible, the present level of the Forum not having been excavated down to its earlier Augustan paving until the 19th century.

The Rostra

|

|

The structure derives its name from the six rostra (rams that were mounted on the sides of a warship) which were captured during the victory at Antium in 338 BC. Originally, the term meant a single structure located within the Comitium space near the Forum and usually associated with the Senate Curia. It began to be referred to as the Rostra Vetera ("Elder Rostra") in the imperial age to distinguish it from other later platforms designed for similar purposes which took the name "Rostra" along with its builder's name or the person it honored.

As you can see if you have been following along on the aerial view, there are two partial columns that remain on the south side of the Rostra, and we got pictures of both of them. The eastern one sits on a brick base and is the taller of the two; the western one is shorter, and pictures of it usually show the Arch of Septimus Severus (and the monument to Vittorio Emanuele II) in the background.

The Basilica Aemilia

|

This building was replaced, in 179 BC, by the Basilica Fulvia-Aemilia. This building was erected by censor Marcus Fulvius Nobilior with the name of Basilica Fulvia. After Nobilior's death, his colleague Marcus Aemilius Lepidus completed it, and it was frequently restored and redecorated by the members of the Aemilian gens, giving the basilica its current name.

The 78 BC, another consul with the name Marcus Lepidus embellished it with the clipei ("shields"). This intervention is recalled in a coin from 61 BC by his son.

According to other scholars, however, the Basilica Aemilia was an entirely different edifice from the Basilica Fulvia, but the question may be moot, insofar as the ruins we see today are concerned.

|

After a fire, Augustus almost completely restored the edifice in 14 BC. In this occasion the tabernae which preceded it towards the Forum square and the portico were totally rebuilt. The two upper floors of the basilica were totally rebuilt. Over the upper order an attic was built, decorated with vegetable elements and statues of barbarians. The basilica was restored again in 22 AD. On its two-hundredth anniversary, the Basilica Aemilia was considered by Pliny to be one of the most beautiful buildings in Rome. It was a place for business and, in the porticus of Gaius and Lucius (the grandsons of Augustus) fronting the Roman Forum, there were the Tabernae Novae (new shops).

On the colored marble floor one still can see the green stains of bronze coins that melted when Rome was sacked by Alaric the Visigoth in 410 AD. There were still major remains of the basilica by the Renaissance, but they were taken and used for a palace which no longer exists. So not much remains today, and what was here was mostly foundations and scattered marble pieces.

The Temple of Saturn

|

The location of the temple is connected to the much older Altar of Saturn, which tradition associates with the god himself founding a settlement on the Capitoline Hill. Construction of the temple is thought to have begun in the later years of the Roman Kingdom under Tarquinius Superbus. Its inauguration by the Consul Titus Lartius took place in the early years of the Republic. The temple was completely reconstructed by Munatius Plancus in 42 BC.

|

The only remaining portion of the temple, and one of the most iconic images in the Forum, is the front facade, which was at the top of the steps leading up from the northeast. This facade was six columns across, although the ruin that currently stands here also has the first in each row of side columns- making a total of eight columns in the ruin. One might wonder why only one of each side column remain, as in the ruins of the Temple of Vespasian (see next section), but to me it seems reasonable that it would be the nature of a corner structure, such a structure being much more stable than a long wall. There is a frieze on the pediment at the top of the columns; it commemorates the restoration undertaken after the fire. The facade was certainly imposing looking up at it from the side.

According to ancient sources, the statue of the god in the interior was veiled and equipped with a scythe. The image was made of wood and filled with oil. The legs were covered with bands of wool which were removed only on December 17, the day of the Saturnalia.

In Roman mythology, Saturn ruled during the Golden Age, and he continued to be associated with wealth. His temple housed the treasury where the Roman Republic's reserves of gold and silver were stored. The state archives and the insignia and official scale for the weighing of metals were also housed there. Later, the treasury was moved to another building, and the archives transferred to the nearby Tabularium. The temple's podium, in concrete covered with travertine, was used for posting bills (since no one, apparently, had put up a sign reading "stipes neque rostro".

The Temple of Vespasian and Titus

|

The Temple of Vespasian was in the Corinthian order, hexastyle (i.e. with a portico six columns wide), and prostyle (i.e. with free standing columns that are widely spaced apart in a row). It was particularly narrow due to the limited space- sandwiched in between the Temple of Saturn and the Capitoline Hill; it was over 100 feet long and 65 feet wide.

Domitian did it up nicely, using white marble outside and travertine inside, lined with marbles imported at great expense from the eastern provinces. The interior was highly ornate and the frieze depicts sacred objects that would have been used as the symbols, or badges, of the various priestly collegia in Rome. Around 200 to 205, the Emperors Septimius Severus and his son, Caracalla, conducted renovations on the temple.

The temple suffered significant damage during medieval times; Pope Nicholas V remodeled the Forum (which involved the demolition of both angles of the temple on the Forum side and the reconstruction of its front as a fortress with corner towers). All that survives today is the podium's core, small parts of the cella's travertine wall, some pedestals and the iconic three Corinthian columns at pronaos's south-east corner.

There was one other ruin in this northwest corner of the Forum, but it was not marked, and so I didn't find out what it was until I began working on this album. The ruin was the remains of the Tabularium. This building was the official records office of ancient Rome, and also housed the offices of many city officials. It was on the front slope of the Capitoline Hill. The Tabularium was first constructed around 78 BC by order of M. Aemilius Lepidus and Q. Lutatius Catulus (the conqueror of the Cimbri). It was later restored and renovated during the reign of the Emperor Claudius, about 46 AD.

|

|

It was also a good place for photographs like the one below:

|

The Arch of Septimus Severus

|

The arch was raised on a travertine base originally approached by steps from the Forum's ancient level. The central archway, spanned by a richly coffered semicircular vault, has lateral openings to each side archway, a feature copied in many Early Modern triumphal arches. The Arch is about 68 feet high and about 76 feet wide. The three archways rest on piers, in front of which are detached composite columns on pedestals. Winged Victories are carved in relief in the spandrels. A staircase in the south pier leads to the top of the monument, on which were statues of the emperor and his two sons in a four-horse chariot, accompanied by soldiers. Above the side arches were intricate relief carvings, and on the bases of the columns there were reliefs of the emperor, his sons, soldiers and other Romans. You can see some of these relief sculptures here.

The Arch stands close to the foot of the Capitoline Hill. A flight of steps originally led to the central opening, but by the 4th century erosion had raised the level of the Forum so much that a roadway was put through the Arch for the first time. So much debris and silt eroded from the surrounding hills that the arch was embedded to the base of the columns. The damage wrought by wheeled medieval and early modern traffic can still be seen on the column bases, above the bas-reliefs.

|

During the Middle Ages repeated flooding of the low-lying Forum washed in so much additional sediment and debris that when Canaletto painted it in 1742, only the upper half of the Arch showed above ground. The well-preserved condition of the arch owes a good deal to its having been incorporated into the structure of a Christian church. When the church was refounded elsewhere, the arch remained ecclesiastical property and was not demolished for other construction.

I took some other pictures of the arch and some of the surrounding buildings that I wanted to include here. There are clickable thumbnails below for these pictures:

|

The Museum at the Forum

|

To view the slideshow, just click on the image at left and I will open the slideshow in a new window. In the slideshow, you can use the little arrows in the lower corners of each image to move from one to the next, and the index numbers in the upper left of each image will tell you where you are in the series. When you are finished looking at the pictures, just close the popup window.

The visit to the museum brought our walk through the Roman Forum to an end, and so we walked to the exit from the Forum area that was just between the Basilica Aemilia and the Temple of Antoninas and Faustina. This brought us up to the main avenue that runs northwest along the side of the Forum area. We turned northwest along that street, and this brought us alongside the Forum of Caesar. While I had seen this forum on my way back from the Vatican three days ago, Fred had not seen it, so we spent a bit of time here.

|

The Forum of Caesar originally meant an expansion of the Forum Romanum. The Forum, however, evolved so that it served two additional purposes: it became a place for public business that was related to the Senate and it was a shrine for Caesar himself. (Although there was probably one there from the beginning, there is a much more recent bronze statue of Caesar in the middle of the Forum area. Near the north end are the three iconic remaining columns of the Temple of Venus Genetrix that Caesar made part of the Forum project.

We came around in front of the Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II so that Fred could have a look at it (he was not with me when I first stopped by to see it three days ago), we crossed the Piazza Italia and headed north towards the Pantheon.

If you have been following us on the aerial view of the Forum walk, you can close that window now.

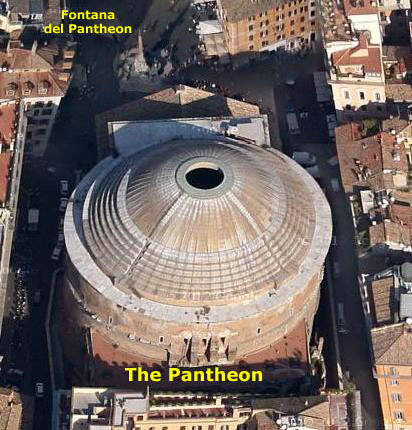

A Look Inside the Pantheon

|

|

When we came through the Piazza in front of the Pantheon with Frederico, the building was closed, and it was then that Fred and I decided we would have to revisit it so we could go inside, and that's why we are stopping here again today.

|

A rectangular vestibule links the porch to the rotunda, which is under a coffered concrete dome, with a central opening (oculus) to the sky. Almost two thousand years after it was built, the Pantheon's dome is still the world's largest unreinforced concrete dome. The height to the oculus and the diameter of the interior circle are the same- 142 feet.

The Pantheon is one of the best-preserved of all Roman buildings. It has been in continuous use throughout its history; since the 7th century, the Pantheon has been used as a Roman Catholic church dedicated to "St. Mary and the Martyrs" and so known as "Santa Maria della Rotonda." The square in front of the Pantheon is called Piazza della Rotonda, and it features the Fountain of the Pantheon.

Just across the square from the Pantheon, Fred happened to notice a small shop with some beautiful tropical hibiscus surrounding the doorway, and so he had me stop so he could take a picture.

Three days ago, all we could do was peek into the interior through a gap in the closed doors, and what we could see seemed quite beautiful, so we were looking forward to actually getting inside today.

|

The dome features sunken panels (coffers), in five rings of 28. This evenly spaced layout was difficult to achieve and, it is presumed, had symbolic meaning, either numerical, geometric, or lunar. In antiquity, the coffers may have contained bronze stars, rosettes, or other ornaments.

Circles and squares form the unifying theme of the interior design. The checkerboard floor pattern contrasts with the concentric circles of square coffers in the dome. Each zone of the interior, from floor to ceiling, is subdivided according to a different scheme. As a result, the interior decorative zones do not line up. The overall effect is to immediately orient the viewer to the major axis of the building, even though the cylindrical space topped by a hemispherical dome is inherently ambiguous. Sadly, this immensely interesting discordance has not always been appreciated; the attic level was redone according to Neoclassical taste in the 18th century.

|

As one might expect, there were a great many changes made to the interior when the Pantheon was converted from a building dedicated to the entire "pantheon" of Roman gods to a building dedicated to a single, decidedly non-Roman one. The niches and chapels around the interior now contain a great many Christian paintings, sculptures and frescoes.

|

The Inside of the Pantheon |

When you first enter the Pantheon, you are facing the high altar on the far side of the room. That altar and the apses were commissioned by Pope Clement XI (1700–1721) and in one apse a copy of a Byzantine icon of the Madonna is enshrined. The original, now in the Chapel of the Canons in the Vatican, has been dated to the 13th century, although tradition claims that it is much older. The choir was added in 1840.

The first niche to the right of the entrance holds the fresco "Madonna of the Girdle and St Nicholas of Bari" (1686), and the first chapel on the right, the Chapel of the Annunciation, has a fresco of "The Annunciation." On the left side is a canvas of "St Lawrence and St Agnes" (1645–1650), and on the right wall is the "Incredulity of St Thomas" (1633).

The second niche has a 15th-century fresco- the "Coronation of the Virgin." In the second chapel is the tomb of King Victor Emmanuel II (died 1878); work began on the tomb in 1885. It consists of a large bronze plaque surmounted by a Roman eagle and the arms of the house of Savoy. The golden lamp above the tomb burns in honor of Victor Emmanuel III, who died in exile in 1947.

The third niche has a sculpture entitled "St Anne and the Blessed Virgin." In the third chapel is a 15th-century painting- "The Madonna of Mercy between St Francis and St John the Baptist." It is also known as "The Madonna of the Railing," because it originally hung in the niche on the left-hand side of the portico, where it was protected by a railing. It was moved to the Chapel of the Annunciation, and then to its present position sometime after 1837. The bronze epigram commemorates Pope Clement XI's restoration of the sanctuary. On the right wall is the canvas of "Emperor Phocas presenting the Pantheon to Pope Boniface IV" (1750). There are three memorial plaques in the floor, and the final niche on the right side has a statue of St. Anastasio (1725).

In the first niche to the left of the entrance is an "Assumption" (1638), and the first chapel on the left is the Chapel of St Joseph in the Holy Land; it is also the chapel of the Confraternity of the Virtuosi, referring to the fraternity of artists and musicians that was formed here by a 16th-century Canon of the church, to ensure that worship was maintained in the chapel. The fraternity still exists- now called The Pontifical Academy of Fine Arts. The altar in the chapel is covered with false marble, and above it is a statue of St Joseph and the Holy Child.

Below, left, there are some clickable thumbnails for some pictures that Fred took inside the Pantheon while I was making the movie that introduced this section.

|

The third niche holds the mortal remains of the great artist Raphael. The sarcophagus was given by Pope Gregory XVI, and the translation of the Latin inscription reads: "Here lies Raphael, by whom the mother of all things (Nature) feared to be overcome while he was living, and while he was dying, herself to die". There is an 1833 bust of Raphael, and behind the tomb is the statue known as the Madonna of the Rock, so named because she rests one foot on a boulder.

In the Chapel of the Crucifixion, the Roman brick wall is visible in the niches. There is a 15th‑century wooden crucifix on the altar, and on the left wall is "Descent of the Holy Ghost" (1790). On the right side is the low relief "Cardinal Consalvi presents to Pope Pius VII the five provinces restored to the Holy See" (1824). There is a bust of Cardinal Agostino Rivarola, and the final niche on this side has a statue of St. Rasius (St. Erasio) (1727).