|

June 3, 2012: An Excursion to Tivoli and Villa d'Este |

|

June 1, 2012: Rome, Italy: Day One |

|

Return to the Index for Our Week in Florence and Rome |

Today is our first full day here in Rome, and with Frederico as our guide, we are going to do as much as we can. Before he arrived at the apartment, Fred and I took a walk down near the Colosseum to Trajan's Baths. Then the four of us set out from the apartment, eventually walking about two miles northwest across the city to the Spanish Steps. From there, we walked southwest to the Pantheon. From there, we headed over to the Tiber River to meet up with Frederico's friend Gaspar, and the five of us walked north along the river towards Castel Sant' Angelo. Fred and I went into the castle for a tour, and then the five us walked the short distance to St. Peter's Cathedral and the Vatican. From there, we returned to the apartment, ending the day later on with dinner in the neighborhood nearby.

Fred and I Tour the Ruins of the Baths of Trajan

We left the apartment out onto Via Cavour and headed southwest, since we knew that this main street would eventually run into the ruins area of the ancient Forum, and that the park containing the ruins of the Baths of Trajan would be near the Colosseum, off to our left. Just south of the apartment we crossed the diagonal street that leads from where the apartment is over to the Monumento Vittorio Emmanuele (something to see later).

|

Photographs help, but no matter how many one looks at, whether they be casual snapshots or professional photographs in books, one can never really get the "feel" of a place; one can never put oneself there and begin to see and experience things as the people who actually live there do. And it's not just Americans; for every one of us who might wish to experience Rome, there is an Italian who probably wishes to experience an American city- like Dallas. Sadly, unless they actually visit here, all they have to go on are the photographs, movies, books and TV shows that they see, and none of these can really provide the experience of being in Dallas. (Some of them, notably the TV shows, don't provide a realistic look at all; Dallas has no Ewings, and very little of the "drama" that supposedly goes on.

This is why this online photo album is so detailed. As my friend Greg has pointed out, some people "photograph" while I tend to "document." That's what all the maps, aerial views, movies and commentary are for- to document, as thoroughly as I can, the places I have visited. But the documentation is not for me; I can close my eyes and visualize almost any of the places, here and abroad, that I have explored in my travels. I can do this because I was actually there. But you weren't, and while photographs are nice, they provide no "context", no sense of "being there."

Google, Inc. has helped; they have provided world maps integrated them with satellite imagery (the 45° view is particularly stunning, where it is available), and allowed photographs all over the Internet to be linked to that mosaic. But what I find really amazing are the "street views-" that seamless collection of many millions of photographs that Google has commissioned. Using this view (accessible from Google Maps) one can (virtually) move up and down a street, turning one's head this way and that to see 360° around from any spot- just as if one was standing there. "Street View" is mind-boggling, and you should definitely try it.

Why I have waited this long to mention all this I don't know, but I am going to take this opportunity to introduce you to Google "Street View." I am going to have you walk with us from our apartment at 98 Via Cavour to the Basilica San Pietro, which is located about twelve blocks away to the south in the plaza formed by the intersection of Via delle Sette Sale and Via Eudossiana. (See the aerial view above.) I am going to capture some of Google's photographs for this short trek; they are below, in sequence. I think you will be impressed (not with me or with this album, but with what Google has done and provided to you essentially for free).

(1) 98 Via Cavour (from across the street) |

(2) The View South Down Via Cavour |

(3) One Block South, Looking Left |

(4) One Block South, Looking Down Via Cavour |

(5) Further South Along Via Cavour |

(6) Further South Along Via Cavour |

(7) Approaching Via Cavour & Via In Selci |

(8) At Via Cavour & Via In Selci |

(9) Turning Left, Looking Across Via In Selci |

(10) Crossing Via In Selci to Via Polacco |

(11) Looking Back Down Via Monte Polacco |

(12) Turning Right, Looking Down Via Sette Sale |

(13) Going Down Via della Sette Sale |

(14) Approaching the Plaza at Via Eudossiana |

(15) At the Plaza |

(16) Looking Left to Basilica San Pietro Steps |

Well, that's what street view can do for you. Of course, they don't replace personal photos, such as this one of Fred at the foot of the Via Monte Polacco stairs, but they certainly are interesting. Our short walk brought us to the entrance to the Basilica de San Pietro in Vincoli.

|

The basilica has undergone several restorations, culminating in an almost complete rebuilding by Cardinal Della Rovere (who became Pope Julius II in 1503). The front portico was added in 1475 and the cloister in 1493. Other work has been done since. (Two popes were elected in this church- Pope John II in 533 and Pope Gregory VII in 1073.

The interior of the basilica has a nave and two aisles, with three apses divided by antique Doric columns. The aisles are surmounted by cross-vaults, while the nave has an 18th century coffered ceiling, frescoed in the center by Giovanni Battista Parodi, portraying the Miracle of the Chains (1706).

Michelangelo's Moses, completed in 1515, was originally intended as part of a massive 47-statue, free-standing funeral monument for Pope Julius II; it is now the centerpiece of the Pope's funeral monument and tomb here. Moses is depicted with horns, connoting "the radiance of the Lord", due to the similarity in the Hebrew words for "beams of light" and "horns". This kind of iconographic symbolism was common in early sacred art, and for an artist horns are easier to sculpt than rays of light.

Other works of art include two canvases of Saint Augustine and St. Margaret, the monument of Cardinal Girolamo Agucchi and a sacristy fresco depicting the Liberation of St. Peter. The tomb of Cardinal Nicholas of Kues (d 1464) has a relief- "Cardinal Nicholas before St Peter." Other tombs include those of painter and sculptor Antonio Pollaiuolo and of Cardinal Cinzio Aldobrandini, the latter decorated with imagery of the Grim Reaper.

|

In the Basilica di San Pietro in Vincoli |

We took a number of other pictures of the architectural elements and the beautiful artwork here in the basilica. You can use the clickable thumbnails below to have a look at the best of these:

|

When we came out of the basilica, we could look across the plaza (the view is here) where there was another small church (and it's bell tower) alongside the Institute for Restoration for the city of Rome. If you look carefully between those two buildings, you can barely see the top of the Monument to Vittorio Emmanuele, which is about a mile away in the direction of the Vatican. We'll be going by it later, and get some good pictures of the imposing structure, but when we do, we will be so close to it that it will be difficult to get pictures of the equestrian sculptures that crown both towers on each side of the building. That's why it's interesting that Fred chose this time to use his zoom lens to get a picture of those two sculptures. But more about them later when we visit the monument.

For now, we left the plaza towards the southeast, heading towards the nearby park where the ruins of the Baths of Hadrian can be found. To enter the park, we had to swing a bit south, following the west edge of the park and heading directly towards the Colosseum.

|

Then we came very close to the Colosseum itself- so close that I had to combine two pictures to form the single view at left. Fred also took some good pictures of the famous structure, and there are clickable thumbnails for them below:

|

From the Colosseum, we walked north to enter the Parco del Colle Oppio- the Park on Oppian Hill.

|

Historically, the hill was the site of one of the villages from which Rome was founded, and this memory was kept alive through the Republican period, as inscriptions found in the area cite continued restoration efforts paid for by the local inhabitants. This particular area was part of Region 3 of the city, the region being called "Isis and Serapis" after the great temple that stood on its southeastern slopes.

Already home of the Portico of Livia, the hill was the site of the "Golden House"- a large landscaped portico villa built by the Emperor Nero. Subsequently, the Baths of Titus and Trajan were located here. In the Christian era, the Basilica San Pietro and the church of San Martino were sited here.

Today, the area is part of Rome's Monti district (one of Rome's "green lungs," or open park areas). The surrounding streets were all built up between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, while the archaeological remains (what was left of them, at least, after many were pillaged) were included in the vast Park of Oppian Hill, which slopes down to the valley of the Colosseum.

The huge part has two main portions- the southern one, where almost all the ancient ruins are located, and an area on the north side where the gardens are.

|

In 1871 , as part of the urban reorganization that took place when the Italian capital moved from Florence to Rome, the area formally became a public garden. But it was under the fascist dictatorship (1928-1936) that the Oppian Park assumed its current form. This was undoubtedly due, at least in part, to the fascist preoccupation with all things nationalistic and patriotic, as the pillaging of ruins sites was brought to a halt. Today, the park and gardens cover 27 acres.

Even in the section of the park that we walked through, there were fountains (like this one, that is apparently used by the many dog walkers) benches, walkways, sculptures (one that we saw seemed to be of two amphora) and plantings- all amid the ruins of the Baths of Trajan. Below are clickable thumbnails for some of the other pictures we took that aren't really of the ruins themselves:

|

Of course, the main reason we'd walked down here this morning was to see the ruins of the Baths of Trajan.

The Baths of Trajan were a massive thermae, a bathing and leisure complex, built in ancient Rome and completed in 109. Commissioned by Emperor Trajan, the complex of baths occupied space on the southern side of the Oppian Hill on the outskirts of what was then the main developed area of the city, although still inside the boundary of the Servian Wall. The architect of the complex is said to be Apollodorus of Damascus. After being utilized mainly as a recreational and social center by Roman citizens, both men and women, for many years, the baths, in use as late as the early 5th century seem to have been deserted at the time of the siege of Rome by the Goths in 537; with the destruction of the Roman aqueducts, the thermae were abandoned, as was the whole of the now-waterless Oppian Hill.

|

The bath complex was immense by ancient Roman standards, covering an area of approximately 1000 by 600 feet. The complex rested on a northeast-southwest axis, with the main building attached to the northeast wall. This was contrary to the more widely used north-south axis of many buildings in the vicinity. It is suggested that this unorthodox orientation was chosen by the architects to reduce the bathers' exposure to the wind, while also maximizing exposure to the sun.

Within the complex, the building was surrounded by a large grassy area. The baths themselves consisted of pools, including a tepidarium (warm area), a caldarium (hot pool and dry, sauna-like area), frigidarium (cool pools), and also gymnasia, and apodyteria (changing rooms). In addition to the facilities of the bath complex used by the public, there was a system of subterranean passageways and structures used by slaves and workers to service and maintain the facilities. Also underground, the massive cistern, surviving today as the Sette sale, the "seven rooms", stored much of the water used in the baths. It was capable of storing no less than 2 million gallons.

You can mentally fit the plan above into the aerial view of the archaeological portion of Oppian Hill park below; fit the two semi-circular ruins- one at the left and one at the upper right in the aerial view- with the similarly-positioned semicircular structures from the plan above:

|

There were four of these extensions, "excedrae," around the structure. Two are similar and were on the southwestern and southeastern corners of the structure. The other two are also similar and were positioned near the northwest and northeast corners. The southwestern excedra, 100 feet in diameter, has always been visible over the centuries, and is depicted in many prints and paintings. (The northeastern excedra has been extensively restored, and was not always so complete as it is today.)

|

Southwestern Excedra Plan |

Recent excavations have shown that along the inner perimeter, beneath the niches, there are concentric wide tiers, and on the top tier there was a slim colonnade that supported a balcony from which one could reach the niches on the upper level, confirming that they were functional. These tiers also served as seats for people attending public readings or meetings. There are drawings and game boards engraved in some of the surviving floor slabs which indicate the people also engaged in less serious pursuits here.

|

|

As we wandered through the park, we took a few other good pictures of some of the ruins that we saw. I didn't notice any signs near them or I would add more detail here. But you can use the clickable thumbnails below to wander around with us:

|

From the northeastern excedra, we left the park and walked back to the stairs along Via Sete Sale. At the top of the stairs we'd climbed up earlier, I took one more picture of Fred before we went down them again to Via Cavour and headed back to the apartment.

Rome Walking Tour Part 1:

From Our Apartment to The Spanish Steps

|

As a first stop, we headed over to the church nearby to take some pictures and go inside. Then we followed Frederico as we headed generally northwest across the center of Rome to end the first segment of our walk at The Spanish Steps.

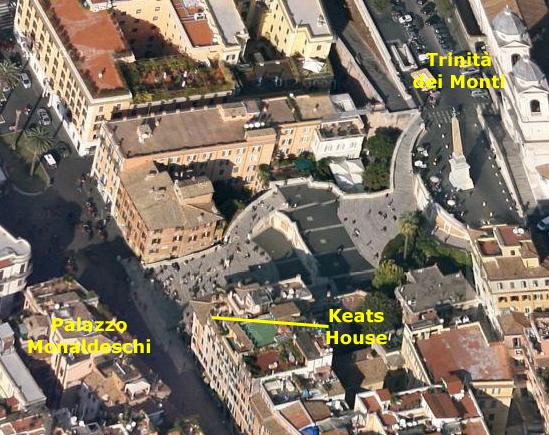

As I have done before, I have put together an aerial view of the part of Rome that we'll be traversing on our way to the Spanish Steps. This time, I have used Google's "45° view" that allows you a better look at the buildings and other features. On this view, I've marked the places we stopped and have, where informative, shown you the path we followed.

|

We left the apartment building with Frederico, turned right up Via Cavour heading towards the main train station.

Basilica Papale Santa Maria Maggiore (Papal Basilica of Saint Mary Major)

|

To be a "basilica" requires either apostolic grant or immemorial custom, and this is one of only four that today have the designation of a "major basilica" (Saint Peter's being one of the other three). The title was once used more widely, but now all churches other than these four are called "minor basilicas," a term I have used already in our travels.

History

The present church was built under Pope Sixtus III (432-440). In addition to this church on the summit of the Esquiline Hill, Pope Sixtus III commissioned extensive building projects throughout the city, which were continued by his successor Pope Leo I, the great. The church retains the core of its original structure, despite several additional construction projects and damage by the earthquake of 1348. Church building in Rome in this period was inspired by the idea of Rome being not just the center of the Empire but of the entire Christian world.

Santa Maria Maggiore, one of the first churches built in honor of the Virgin Mary, was erected in the immediate aftermath of the Council of Ephesus of 431, which proclaimed Mary as Mother of God. and commemorates that decision. This decision and the atmosphere surrounding it influenced the creation of the mosaics that adorn the interior- especially in the nave and on the triumphal arch. But the magnificence of this church and other Catholic buildings was also the result of the abundant revenue accruing to the papacy at the time from land holdings acquired by the Church during the 4th and 5th centuries.

When the popes returned to Rome after the period of the Avignon papacy, the buildings of this basilica became a temporary Palace of the Popes, due to the deteriorated state of the Lateran Palace. The papal residence was later moved to the Palace of the Vatican in what is now Vatican City. The basilica was restored, redecorated and extended by various popes; in the 1740s Benedict XIV commissioned the present façade and a broad renovation of all of the church's altars.

Architecture

The original architecture of Santa Maria Maggiore was classical and traditionally Roman, but even though it is immense in its area, it was built to plan. The design of the basilica was a typical one for the time- a tall and wide nave with an aisle on either side and a semicircular apse at the end of the nave. What set Santa Maria Maggiore apart were the beautiful mosaics found on the triumphal arch and in the nave. Also of note are the decorative elements on the outside of the building. A series of sculptures of religious figures, placed in niches, surround the building at the second level.

|

|

The Marian column in the Piazza was erected in 1614, and has been the model for numerous Marian columns erected in Catholic countries. It celebrates the famous icon of the Virgin Mary now enshrined in the Borghese Chapel of the Basilica. It is known as Salus Populi Romani, or Health of the Roman People or Salvation of the Roman People, due to a miracle in which the icon helped keep plague from the city. The icon is at least a thousand years old, and according to a tradition was painted from life by St Luke the Evangelist using the wooden table of the Holy Family in Nazareth. At the base of the column, the fountain by Maderno combines the armorial eagles and dragons of Paul V.

Of course we wanted to enter the basilica, so from the Piazza we walked up the broad steps to the portico towards the broad doors. To the right upon entering the portico stands a statue of King Phillip IV of Spain, one of the Basilica's benefactors.

Interior

In 1995, a new, rose window in stained glass was created for the main façade, reaffirming the declaration of the Second Vatican Council that Mary is the link that unites the Church to the Old Testament. To symbolize the Old Testament, the artist used the seven-branched candlestick, for the New Testament, the chalice of the Eucharist. Fred got an excellent close-up of the window, and you can see it here.

|

Statuary is an important part of the interior decoration of the basilica; some of the subjects were religious figures and some was found on the various memorials and crypts. Below are clickable thumbnails for some of these sculptures:

|

I made two good movies here in Santa Maria Maggiore. One is a general view looking around the inside of the main chapel- the nave and its side aisles. Even if you haven't looked at many of the pictures above, you should definitely watch this movie, as it will show all the main features talked about above. The other is a movie that I made inside the Sistine Chapel (described below), and it, too, will give you a very good feel for what both of the major side chapels are like. Players for these movies are below:

|

The Interior of Santa Maria Maggiore |

The Sistine Chapel in Santa Maria Maggiore |

Under the high altar of the basilica is the Crypt of the Nativity or Bethlehem Crypt, with a crystal reliquary designed by Giuseppe Valadier said to contain wood from the Holy Crib of the nativity of Jesus Christ. This is the burial place of Saint Jerome, the 4th-century Doctor of the Church who translated the Bible into the Latin language. Fragments of the sculpture of the Nativity believed to be by 13th-century Arnolfo di Cambio were transferred to beneath the altar of the large Sistine Chapel off the right transept of the church. (This chapel is named after Pope Sixtus V; the Sistine Chapel of the Vatican is named after Pope Sixtus IV.) The main altar in the chapel has four gilded bronze angels holding up the ciborium, which is a model of the chapel itself.

Beneath this altar is the Oratory or Chapel of the Nativity, on whose altar, at that time situated in the Crypt of the Nativity below the main altar of the church itself, Saint Ignatius of Loyola celebrated his first Mass as a priest on 25 December 1538. Just outside the Sistine Chapel is the tomb of Gianlorenzo Bernini and his family.

I want to include here some of the other good pictures we took here in Santa Maria Maggiore; they are of individual artworks, small chapels and memorials. You can use the clickable thumbnails below to have a look at them:

|

After a half hour here in Santa Maria Maggiore, the three of us left, and went around the north side of the basilica to begin to head westward across the city. Behind the basilica, between it and Via Cavour, is the Piazza del Esquilino. The piazza is named for, and is on the crest of, one of the Seven Hills, and the 50-foot obelisk in the center of it stands out. Two obelisks were found in the 16th century; Sixtus V had one erected here and the other in Piazza Quirinale. This one comes from the entrance to the Mausoleum of Augustus. From this square only the back of the Basilica Santa Maria Maggiore can be seen.

Piazza della Repubblica

|

The fountain in this square was originally the fountain of the Acqua Pia (connected to the aqua Marcia aqueduct), commissioned by Pope Pius IX in 1870. Completed in 1888, it originally had four chalk lions designed by Alessandro Guerrieri. These were then replaced in 1901 with sculptures of Naiads. The naiads represented are the Nymph of the Lakes (recognisable by the swan she holds), the Nymph of the Rivers (stretched out on a monster of the rivers), the Nymph of the Oceans (riding a horse symbolizing of the sea), and the Nymph of the Underground Waters (leaning over a mysterious dragon). In the centre is a sculpture symbolizing the dominion of the man over natural force.

|

In Piazza della Repubblica |

It is the southwestern side of the piazza whose dimensions generally follow those of the excedra of the baths. The original porticos have been incorporated into the two curved buildings that were added more recently. These buildings blend in well to the piazza, and both of them have a great deal of beautiful ornamentation on their facades and cornices.

We walked around the piazza and across the street to visit the basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri. It was interesting for a number of different reasons, not the least of which was the name of its architect- Michelangelo- who used the original frigidarium of the baths as the basis for the wings of its spacious Greek cross plan.

|

Once in the basilica, we started taking pictures of some of the alcove chapels and spaces; there are clickable thumbnails below for a few of these:

|

|

Inside Santa Maria degli Angeli |

The inside of the basilica was beautiful and, because it was a Greek cross, unusual without the standard long, rectangular nave. I suppose that masses are held in the various wings; there were pews in all of them.

We took lots of pictures inside the basilica, and I've pared down that large number to just six, and there are clickable thumbnails for them below:

|

The most unusual aspect of this basilica, and something we haven't encountered before, was its concentration on science- in particular, astronomy and time.

|

This church was chosen for several reasons: (1) Like other baths in Rome, Diocletian's was already naturally southerly oriented, so as to receive unobstructed exposure to the sun; (2) the height of the walls allowed for a long line to measure the sun's progress through the year more precisely; and (3) the ancient walls had long since stopped settling into the ground, ensuring that carefully calibrated observational instruments set in them would not move out of place. (The fact that it was constructed in a "pagan" building would also symbolically represent a victory of the Christian calendar over the earlier pagan one.)

Bianchini's sundial was built along the meridian that crosses Rome. At solar noon, the sun shines through a small hole in the wall to cast its light on this line each day. At the summer solstice, the sun appears highest, and its ray hits the meridian line at the point closest to the wall. At the winter solstice, the ray crosses the line at the point furthest from the wall. At either equinox, the sun touches the line between the these two extremes. The longer the meridian line, the more accurately the observer can calculate the length of the year. The bronze meridian line built here is 45 meters long and embedded in yellow-white marble.

In addition to using the line to measure the sun's meridian crossing, Bianchini also added holes in the ceiling to mark the passage of stars. Inside the interior, darkened by covering the windows, Polaris, Arcturus and Sirius were observed through these holes with the aid of a telescope to determine their right ascensions and declinations. The meridian line was restored in 2002 for the tricentenary of its construction, and it is still operational today.

The basilica was an interesting place, but there was much more to see and do, so we headed outside, hung a right and continued to walk northwest along Via Quirinale in the general direction of The Spanish Steps.

About two blocks up the street, we came to a small plaza where Via XX Settembre crossed the street we were walking. As we came to the plaza, we saw the facade of Santa Susanna church across the plaza to our left. This church is unusual as is was founded by an American order- the Paullist Fathers.

|

To the Paulists, the church seemed perfectly located. It was near the American embassy, many government ministries and a number of apartment buildings where Americans lived. Returning to America, Burke appointed Father Thomas O'Neill as the first Procurator General of the Paulists. O'Neill and his assisnt returned to Rome that same year. Thomas Burke discussed the church with his brother, John Burke, also a Paulist Father. He, in turn spoke with President Harding about acquiring the church. When the Apostolic Nuncio paid a visit to the White House in June, he was surprised to hear President Harding express a desire for an American church in Rome- and specifically Santa Susanna. The Nuncio wrote the Vatican Secretary of State and recommended that the Americans be given the church as a gesture that would bring about much good will. By the end of the year Pope Benedict XV had authorized the Paulists to use the Church of Santa Susanna to create a national church for American Catholics in Rome.

Father O'Neill took possession of the church on January 1, 1922, receiving the keys to the front door from the Cistercian sisters. The new rector set out to find a carpenter in Rome who could build pews, an American tradition that made the church quite an oddity during the 1920s. He built a "winter wall," a second set of doors inside the main doorway to keep out the weather; this was also odd as the tradition had been to use a heavy leather curtain. Finally, he added an electric light system, the first of its kind in Rome. As Roman churches were lit only by candlelight, this caused quite a controversy. (That system remained in use until 2012, when a new system was mandated by code.

The first public Mass for the American community was postponed twice- first because of the death of Pope Benedict XV, an event that brought everything in Rome to a halt. The Mass was delayed a second time after Il Messagero reported that the church had been "given" to the American community and that another Italian treasure had been lost. It took two weeks for the Vatican to straighten everything out. The first Sunday Mass for the American community was finally celebrated on February 26, 1922. American Cardinal O'Connell, still in Rome after the papal conclave, presided, and American Ambassador Childs attended together with much of the English-speaking community. The church remained open throughout the day for the first time in many years. Thousands of Italians, among whom were many of the noble families of Rome, came by to visit the church and to see the frescoes. American Cardinals regularly celebrated and preached at the church when they were in Rome. In 1946, an American Cardinal became the titular Cardinal of the church- the first time an American Cardinal became the "owner" of a European church. Santa Susanna had become the American National Church in Rome.

|

The three-arched Fontana dell'Acqua marked the entry of the new water source into Rome, with the conventional "mostra" or showy terminus. But no one liked the structure. One critic said that it was scarcely conceivable that such mediocrity was possible only two decades after the death of Michelangelo. Its disproportionately large attic, a billboard for the triumphant inscription, has an unbalanced stagey flatness; its proportions were unfavorably compared to all the other such structures.

It featured, as ancient Roman fountains did, an inscription honoring its builder, Pope Sixtus. beneath angels holding the papal coat of arms. Within each of the three arches were sculptures on Old Testament subjects. The central arch featured a large statue of Moses, made in 1588 by Leonardo Sormani and Prospero da Brescia. To the left is Aaron, sculpted by Giovanni Battista della Porta and to the right is Joshua sculpted by Flaminio Vacca and Pietro Paolo Olivieri. Water flows from the statues into basins, where four lions are spouting water.

The statue of Moses was criticized at the time for its large size, not in proportion with the other statuary (you can see all three here), but the fountain achieved its political purpose; it was a statement of how the Catholic Church, unlike the Protestant Reformation, was serving the needs of the people of Rome. It also achieved its social purpose of reviving the Quirinal neighborhood; what had been a rustic area of villas was turned into a thriving urban neighborhood by the arrival of a good drinking water supply.

We continued walking through plaza, past an interesting monument (the purpose of which I did not record) and then followed the curve of the boulevard around to our left. The street headed west for a while until we came out into another small plaza- actually the intersection of a few streets. At the west end of the plaza, we came across an interesting fountain- this one of a male figure refreshing himself by pouring water from an amphora over his head. I believe he was sitting in or on a large shell.

|

|

The Spanish Steps and Piazza di Spagna

In front of the church stands the Obelisco Sallustiano, one of the many obelisks in Rome, moved here in 1789. It is a Roman obelisk in imitation of Egyptian ones, originally constructed in the early years of the Roman Empire for the Gardens of Sallust near the Porta Salaria. The hieroglyphic inscription was copied from that on the obelisk in the Piazza del Popolo (which we'll visit on another walk). At the top of the obelisk is ornamentation in the French style, based on the fleur-de-lis. And on the base of the obelisk is a dedication to Pope Pius VI.

The obelisk and church form a handsome pair, although the church is not nearly so ornate as many we have visited. The view from below is the best way to experience the two structures.

|

|

Following a competition in 1717 the steps were designed by the little-known Francesco de Sanctis, though Alessandro Specchi was long thought to have produced the winning entry.

|

Between the obelisk and the stairs there is a broad terrace that offers a beautiful view looking down the stairs to Piazza di Spagna and out across Rome to the west and the dome of St. Peter's in the distance.

|

|

You can use the player at right to watch the movie I made as we were heading down the Spanish Steps; it will give you the "feel" of what that was like. And, on the way down to the piazza, we took some good pictures looking around the stairs and down to the piazza; you can use the clickable thumbnails below to have a look at them:

|

This was another situation, like the Colosseum, where we finally got a chance to actually visit a place that we'd read about, seen pictures of, or seen in movies or television shows. It was interesting to be able to experience it.

|

Located at the base of the steps is the main feature of Piazza di Spagna- is the Early Baroque fountain called Fontana della Barcaccia ("Fountain of the Ugly Boat"), built in 1627-29 and often credited to Pietro Bernini, who had been the pope's architect, since 1623 (and the creator of some of the most important masterpieces of Baroque art in the city, including the renowned baldachino of St. Peter's Basilica). With its characteristic form of a sinking ship, the fountain recalls the historic flood of the River Tiber in 1598 and refers to a folk legend whereby a fishing boat carried away by the flood of the river was found at this exact spot. In reality, the sinking boat was ably invented by Bernini to overcome a technical problem due to low water pressure. The sun and bee ornamentation is a symbol of the Barberini family and a reference to Pope Urban VIII who commissioned the work.

The fountain is a very, very popular place for tourists and children.

|

|

In the southeast part of the square stands the Colonna dell'Immacolata (column of the immaculate conception). It is actually located in Piazza Mignanelli, placed aptly in front of the offices of the Palazzo di Propaganda Fide (offices for promulgating the faith). The monument was designed by the architect Luigi Poletti and commissioned by Ferdinand II, King of the Two Sicilies.

The column was dedicated on December 8, 1857 to celebrate the recently adopted (1854) doctrine of the Immaculate Conception. The doctrine had been proclaimed ex cathedra in the papal bull Ineffabilis Deus of Pope Pius IX. The structure is a square marble base with statues of biblical figures at the corners that uphold a column of Cipollino marble 40 feet tall. Atop the column is a bronze statue of the Virgin Mary. The Corinthian column itself was sculpted in ancient Rome, and was discovered in 1777 during the construction of the monastery of Santa Maria della Concezione located nearby. At the base are four statues of Hebrew figures that gave portent of the virgin birth, each accompanied by a quote of a biblical verse in Latin. The figures are Moses(L) and Isaiah(R), (by Ignazio Jacometti and Salvatore Revelli, respectively), David, (by Adam Tadolini), and Ezekiel, (by Carlo Chelli).

From here, we began the second section of our walk that would end at The Pantheon, so if you still have the aerial view of the first part of our walk open, you can close it now.

Rome Walking Tour Part 2:

From the Spanish Steps to The Pantheon

|

From the Spanish Steps we walked down the street towards Piazza Mignanelli and past Column of the Immaculate Conception. Then we turned west to head down Via Fratina; we were going to follow a zig-zag route down towards the Pantheon, just going down the side streets as we chose. Just a short way down the street, I happened to take a picture of the street ahead of us; notice the building at right in the picture- the one with the name of the street on it. When I was preparing the aerial view of our route, I happened to notice that same building, and just for interest I have marked it for you. As we wound our way through the streets, we passed one store where I just had to get a picture of Fred and Frederico.

|

The convent attached to the church was used first as the Ministry of Public Works, then the Post Office building. One part is still used by the Pallottini fathers, who are in charge of the church. In the square are also the palaces of Acqua Pia Antica Marcia and Marignoli.

Making a few more turns through the streets, we passed another small church. As I was walking along the street in front of it, I happened to glance down and saw what we would call a manhole cover. Most times, when you see them, the city name or the name of the electric or water company is stamped on it. This one was different; you can look at it here. In case you haven't studied Latin or Ancient History, or seen "Cleopatra" or some other more notable movie set in the time of the Roman Empire, you might not know that "S.P.Q.R." stands for "The Senate and People of Rome." Since the classical Roman Senate no longer exists, I found the inscription anachronistic.

Continuing our walk, we eventually came out in the northeast corner of Piazza Colonna.

|

The original dedicatory inscription no longer exists, so it is not known whether it was built during the emperor’s reign (on the occasion of the triumph over the Marcomanni, Quadi and Sarmatians in the year 176) or after his death in 180; however, an inscription found in the vicinity attests that the column was completed by 193. It originally stood on the north part of the Campus Martius, in the centre of a square. This square was probably next to the temple of Marcus Aurelius, but nothing remains of that structure.

The column’s shaft is about 100 feet high, on a 30-foot-high base, which in turn originally stood on a 10-foot-high platform. The platform is gone, and about 10 feet of the base is below ground level (as a result of the restoration of 1589). The column consists of 27 or 28 blocks of Carrara marble, 10 feet in diameter, hollowed out whilst still at the quarry for a stairway of 190-200 steps within the column up to a platform at the top. This stairway is illuminated through narrow slits into the relief.

In 1589 Pope Sixtus V ordered the whole column restored and adapted to the ground level of that time. Also, the bronze statue of the apostle St. Paul was placed on the top platform, to go with that of St. Peter on Trajan’s Column. (Originally the top platform probably had a statue of Marcus Aurelius, but it had been already lost by the 16th century.) That adaptation also removed the damaged or destroyed original reliefs on the base of garland-carrying victories and representations of subjected barbarians, replacing them an inscription describing the restoration.

In the Middle Ages, climbing the column was so popular that the right to charge an entrance fee was annually auctioned off, with the proceeds going into city coffers. This practice was halted over two centuries ago, and in the twentieth century climbing itself was stopped.

|

One particular episode portrayed is historically attested in Roman propaganda– the so-called "rain miracle in the territory of the Quadi", in which a god, answering a prayer from the emperor, rescues Roman troops by a terrible storm, a miracle later claimed by the Christians for the Christian God.

In spite of many similarities to Trajan’s column, the style is entirely different, a forerunner of the dramatic style of the 3rd century and closely related to the triumphal arch of Septimius Severus, erected soon after. The figures’ heads are disproportionately large so that the viewer can better interpret their facial expressions. The images are carved less finely than at Trajan’s Column, through drilling holes more deeply into the stone, so that they stand out better in a contrast of light and dark. As villages are burned down, women and children are captured and displaced,and men are killed, the emotion, despair, and suffering of the "barbarians" is represented acutely in single scenes and in the figures’ facial expressions and gestures. All the while, the Emperor is represented as a protagonist, in control of his environment.

The symbolic language is altogether clearer and more expressive, if clumsier at first sight, and leaves a wholly different impression on the viewer than does the style of Trajan’s column. There, cool and sober balance; here, drama and empathy. The pictorial language is unambiguous- imperial dominance and authority is emphasized, and its leadership is justified. Overall, it is an anticipation of the development of artistic style into late antiquity, and a first artistic expression of the crisis of the Roman empire that would worsen in the 3rd century.

|

|

The piazza is rectangular. Its north side is taken up by Palazzo Chigi, formerly the Austro-Hungarian empire's embassy, but now a seat of the Italian government. The east side is taken up by the 19th century public shopping arcade Galleria Colonna.

On the south side of the plaza (where the movie begins) there is the Palazzo Ferraioli, formerly the Papal post office, and the little Church of Santi Bartolomeo ed Alessandro dei Bergamaschi (1731-35). On the west side, which doesn't appear in the movie, is the Palazzo Wedekind, built in 1838 using a colonnade of Roman columns taken from Veii. It is on the current site of this Palazzo that the temple of Marcus Aurelius once stood. Even then, the piazza had been a monumental open space.

The fountain in the Piazza, built in 1577, was commissioned by Pope Gregory XIII. It was restored in 1830, and had two sets of dolphins, with tails entwined, sculpted by Achille Stocchi, set at either end of the long basin. The original central sculpture was then substituted with a smaller sculpture and spray.

From where I was standing, at the northwest corner of the Piazza, we went around the north end of Palazzo Wedekind to come into Piazza di Monte Citorio.

|

Between the 9th and 11th centuries, due to fire, earthquake or war, the obelisk collapsed and then, progressively, became buried. Pope Sixtus V (1520–1590) made some attempts to repair and raise the obelisk, reassembling some pieces that had been found in 1502 in a cellar. These failed, but more and more pieces of the original obelisk and horologium were discovered. But there was never enough of it to make a restoration possible. Finally, from 1789 to 1792, Pope Pius VI carried out intensive works to repair the obelisk, including a restoration of the hieroglyphs on the shaft; it was eventually re-raised in approximately its current position and restored as a solar clock. Continued urban renovations kept interfering with the obelisk being used as a solar clock, however. When the Piazza was last modified in 1998, a new meridian was traced on the pavement in honor of Augustus's meridian, pointing towards the main entrance of the palazzo. Unfortunately, the shadow of the obelisk does not point precisely in that direction, and its gnomonic function is definitively lost.

|

In 1696 the Curia apostolica (papal law courts) were installed there; it has also been a city administration building and a police headquarters. As a result of Italian Unification, the capital was moved to Rome in 1870, and Montecitorio was chosen as the seat of the Chamber of Deputies. Only the facade was left intact when the structure was rebuilt in the early 1900s.

When we first entered the piazza, Greg stopped by the palazzo to read the descriptive sign (shown at right). If you would like to read the sign as well, just click on it. When you do, a window will pop up with an enlarged version of the text, and you can learn all about Palazza Montecitorio.

From Piazza di Monte Citorio, we again headed southwest through the picturesque streets of Rome towards the Pantheon. On the way, Fred photographed a public water fountain, and I stuck my head into a corner clock shop. Presently, we came out into Piazza della Rotonda.

|

In the center of the piazza is a fountain, the Fontana del Pantheon, surmounted by an Egyptian obelisk. You can see both the fountain and the obelisk here. The fountain was constructed in 1575 under Pope Gregory XIII; it was one of eighteen new public fountains commissioned by Pope Gregory XIII and supplied by one of the eleven original aqueducts that supplied ancient Rome with drinking water. That aqueduct was reconstructed under Pope Nicholas V in 1453 as the Acqua Vergine. The fountain in the Piazza della Rotonda is of a chalice-type design, about ten feet tall. Due to the slope of the piazza, the fountain is approached by five steps on the south side, and only two on the north.

In 1711, Pope Clement XI had the fountain topped with a 20-foot red marble Egyptian obelisk. The obelisk, originally constructed by Pharaoh Ramses II for the Temple of Ra in Heliopolis, had been brought to Rome to be used in a shrine to the Egyptian god Isis that stood to the southeast of the Pantheon. It was rediscovered in 1374 underneath the apse of the nearby Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, and first erected in the small Piazza di San Macuto east of this square. It is still called the Obelisco Macutèo after its previous location.

|

|

| "The visitor will find himself surrounded by all that is most revolting to the senses, distracted by incessant uproar, pestered with a crowd of clamorous beggars, and stuck fast in the congregated filth of every description that covers the slippery pavement. Nothing resembling such a hole as this could exist in England; nor is it possible that an English imagination can conceive a combination of such disgusting dirt, such filthy odours and foul puddles, such as that which fills the vegetable market in the Piazza della Rotonda at Rome." |

But someone took note, for improvements were made as a result of the urban plan of 1873 and at the direction of Popes Pius VII and Pius IX. The plaza is certainly a lot nicer now, as the movie I made looking around it will reveal. You can watch this movie with the player at right.

The main attraction of the piazza is not the fountain, though, it's the Pantheon which occupies the south side of it.

|

The form of the original Pantheon is debated. Late 19th century excavations indicated that Agrippa's Pantheon faced south, in contrast with its current North-facing layout, and that it had a shortened T-shaped plan with the entrance at the base of the "T". More recent archaeological diggings suggest that the building might have been circular with a triangular porch, and it might have also faced North, much like the later rebuildings.

The Augustan Pantheon was destroyed along with other buildings in a huge fire in 80. Domitian rebuilt the Pantheon, which burned again in 110. Not long after the second fire, construction started again; it was finished by Hadrian but not claimed as one of his works. The original inscription was transferred to the new façade (a common practice in Hadrian's rebuilding projects all over Rome). It was in Cassius Dio's "History of Rome," writing approximately 75 years after the Pantheon's reconstruction, that mistakenly attributed the domed building to Agrippa rather than Hadrian. He did not discuss the purpose of the structure.

|

Since the Renaissance the Pantheon has been used as a tomb, with many notables buried there. Brunelleschi used the Pantheon as help when designing the dome of Florence's Duomo. It was Pope Urban VIII (1623 to 1644) who melted down the bronze ceiling of the portico and used the bronze to make bombards for the fortification of Castel Sant'Angelo.

Two kings of Italy are buried in the Pantheon: Vittorio Emanuele II and Umberto I. Although Italy has been a republic since 1946, volunteer members of Italian monarchist organisations maintain a vigil over the royal tombs in the Pantheon. The Pantheon is still used as a church. Masses are celebrated there, in particular on important Catholic days of obligation and weddings.

We expected to be able to go into the Pantheon, but when we went over to read the sign outside the doors, we found that Saturday was the one day the Pantheon wasn't open. So we had to content ourselves (today at least) with a look around the outside of the building.

|

|

The Pantheon is circular with a portico of large granite Corinthian columns (eight in the first rank and two groups of four behind) under a pediment. A rectangular vestibule links the porch to the rotunda, which is under a coffered concrete dome, with a central opening (oculus) to the sky. Almost two thousand years after it was built, the Pantheon's dome is still the world's largest unreinforced concrete dome. The height to the oculus and the diameter of the interior circle are the same- 142 ft. This is one of the best-preserved of all Roman buildings. It has been in continuous use throughout its history; since the 7th century it has been used as a Roman Catholic church.

It took 732 construction workers over three years to build; 50-foot high columns were planned, but they would have raised the portico so high that it would have closed off the windows that you can see here at the front of the cella, so 40-foot columns were actually used, requiring a number of adjustments to the plan. The grey granite columns were quarried in Egypt's eastern mountains; each weighed 60 tons. They had to be dragged 60 miles from the quarry to the Nile, then floated down the Nile (only during the spring floods was this possible). They were then transferred to vessels to cross the Mediterranean Sea to the Roman port of Ostia. There, they were transferred back onto barges and pulled up the Tiber River to Rome. They were unloaded near the Mausoleum of Augustus, and moved (probably on rollers) the last half-mile to the construction site.

|

We intend to return to the Pantheon either tomorrow or Monday for a look inside, but for now, we'll continue with the third section of our walk through Rome. (If you still have open the aerial view of our path from the Spanish Steps, you can close it now.)

Rome Walking Tour Part 3:

From The Pantheon to the Tiber River to Castel Sant' Angelo

|

From the Pantheon, we took the narrow street to the west; this led us by one of the buildings where some of the original Pantheon columns had been used, and we could look back at the Pantheon Portico from there. At the next street, we headed north to pass by the Church of St. Louis of the French.

|

When the Saracens burned the Abbey of Farfa in 898, a group of refugees settled in Rome; these monks remained in Rome even after their abbey was rebuilt. By the end of the tenth century, the Abbey of Farfa actually owned quite a bit of property in and around Rome, including churches, houses, windmills and vineyards. A bull of Holy Roman Emperor Otto III in 998 confirmed as the abbey's property, three churches- Santa Maria, San Benedetto and the oratorio of San Salvatore.

The abbey eventually ceded much of their property to the Medici family in 1480, and when they did, the church of Santa Maria became the church of Saint Louis of the French. Cardinal Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici commissioned the construction of a new church for the French community in 1518. Building was halted when Rome was sacked in 1527, but the church was finally completed in 1589. A major restoration was carried out 1749 and 1756.

Giacomo della Porta made the façade as a piece of decorative work entirely independent of the body of the structure, a method much copied later. The French character is evident from the façade itself, which has several statues recalling national history: these include Charlemagne, St. Louis, St. Clothilde and St. Jeanne of Valois. The interior also has frescoes by Charles-Joseph Natoire recounting stories of Saint Louis IX, Saint Denis and Clovis.

We made a couple more turns in the side streets heading northwest, went past the Italian Senate, and then negotiated a narrow passageway that brought us into the northern end of Piazza Navona.

Piazza Navona

|

It features important sculptural and architectural creations; at the north end is the Fountain of Neptune:

The Fountain of Neptune |

The statue of Neptune in the northern fountain was added in 1878 to make it more symmetrical with La Fontana del Moro in the south.

|

You can see the other three figures if you use the clickable thumbnails below to see some pictures we took around the fountain:

|

The Nile's head is draped with a loose piece of cloth, meaning that no one at that time knew exactly where the Nile's source was. The Danube touches the Pope's personal coat of arms, since it is the large river closest to Rome. And the Río de la Plata is sitting on a pile of coins, a symbol of the riches America could offer to Europe. Also, the Río de la Plata looks scared by a snake, showing rich men's fear that their money could be stolen. Each river god is semi-prostrate, in awe of the central tower- the slender obelisk- which symbolized Papal power surmounted by the Pamphili symbol (dove). In addition, the fountain is a theater in the round, a spectacle of action, that can be strolled around. Water flows and splashes from a jagged and pierced mountainous disorder of travertine marble.

|

Fountain of the Four Rivers and Piazza Navone |

Standing near the Fountain of the Four Rivers, I made a movie of the fountain, the church of Saint Agnes and some of the piazza; you can watch that movie with the player at right.

Piazza Navona has a third fountain at the southern end; this is the Fontana del Moro with a basin and four Tritons sculpted by Giacomo della Porta (1575) to which, in 1673, Bernini added a statue of a Moor, or African, wrestling with a dolphin.

The Piazza Navone was quite beautiful, surrounded as it was by classic Italian architecture. And the central fountain and obelisk was certainly spectacular.

Heading south from Piazza Navone, we walked down a narrow street to come through a much smaller plaza- Piazza di San Pantoleo. In the center of this plaza, we found a monument to Marco Minghetti (1818-1886), an Italian economist and statesman. As we crossed Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, heading south, we could look down the avenue to the Church of Sant' Andrea della Valle. This basilica church is the general seat for the religious order of the Theatines. We continued south and a couple of blocks later, down some very picturesque streets, we came to Campo di Fiori.

Campo di Fiori

|

Campo di Fiori has never been architecturally formalized; it has always been a focus for commercial and street culture. The surrounding streets are named for trades— Via dei Balestrari (crossbow-makers), Via dei Baullari (coffer-makers), Via dei Cappellari (hat-makers), Via dei Chiavari (key-makers) and Via dei Giubbonari (tailors). Eventually, the square became a part of the Via papale ("Pope's road"), and this brought wealth to the area. A flourishing horse market took place twice a week and a lot of inns, hotels and shops were built. The most famous of them, the "Taverna della Vacca" ("cow's Inn") still stands at the south west corner of the square (it belonged to Vannozza dei Cattanei, the most famous lover of Alexander VI Borgia).

The square also had a "dark side." Public executions used to be held in the square; on 17 February 1600, the philosopher Giordano Bruno was burnt alive for heresy, and all of his works were placed on the Index of Forbidden Books by the Holy Office. In 1887 Ettore Ferrari dedicated a monument to him on the exact spot of his death; the monument has him standing defiantly facing the Vatican. The monument took on new meaning in the first days of a reunited Italy; it became a focal point for freedom of thought.

The demolition of a block of housing in 1858 enlarged Campo de' Fiori, and since 1869 a daily vegetable and fish market has been held there. The ancient fountain known as la Terrina (the "soupbowl") that once watered cattle, was resited in 1889, and replaced with a copy, which is now used to keep flowers fresh. Its inscription ("Do the good and let them talk") suits the gossipy nature of the marketplace. In the afternoons, local games of football give way to set-ups for outdoor cafés. At night, Campo de' Fiori is a meeting place for tourists and young people coming from the whole city. Sadly, in recent years it has become very dangerous at night; there are numerous assaults and confrontations with drunkards and soccer supporters (I understand the redundancy).

The Palazzo and Piazza Farnese

|

The palazzo was commissioned by Alessandro Farnese, who had been appointed as a cardinal in 1493 at age 25, and construction began in 1515. Interrupted by the Sack of Rome in 1527, the size of the palace was increased significantly when, in January 1534, Cardinal Alessandro became Pope Paul III. He also thought a more prominent builder should work on the palazzo, so he employed Michelangelo. The building was to express the power of the Farnese family, and it dominates the Piazza Farnese.

The most important feature of the facade was the balcony Michaelangelo designed; above it is the largest papal stemma, or coat-of-arms with papal tiara, Rome had ever seen. When Paul appeared on the balcony, the entire facade became a setting for his person. On the garden side of the palace, which faced the River Tiber, Michelangelo proposed the innovatory design of a bridge which, if completed, would have linked the palace with the gardens of the Vigna Farnese, Alessandro's holding on the opposite bank. The bridge was never built, although modesty was probably not the reason.

The Farnese had a couple of granite tubs lugged to the Piazza Farnese from the Baths of Caracalla in the 16th century. They commissioned their favorite architect to fashion them into two fountains. Tourists subject to panic attacks upon being reminded of leaving the water in their bathtubs running while they are on vacation should avoid these fountains. Otherwise, they are the only two decorative elements in the wide open Piazza Farnese.

The palazzo was further modified Paul's nephew, who lived in it until his death in 1626, after which it stood virtually uninhabited for twenty years. At the conclusion of the War of Castro with the papacy, Duke Odoardo was able to regain his family properties, which had been sequestered. After his death, Pope Alexander VII allowed Queen Christina of Sweden to lodge in the palace for several months. He must have learned what being a landlord entails, for she proved to be a tenant from hell. After her departure for Paris, the papal authorities discovered that her unruly servants not only had stolen the silver, tapestries, and paintings, but also had smashed up doors for firewood and removed sections of copper roofing.

Palazzo Spada

|

In the Courtyard of Palazzo Spada |

The sculptural decor of the palazzo's front and its courtyard façades feature sculptures crowded into niches and fruit and flower swags, grotesches and vignettes of symbolic devices (impresi) in bas-relief among the small framed windows of a mezzanine; it is one of the richest façades in Rome.

Fred took a good movie in the courtyard, looking around at all the sculpture and other elements; you can watch this movie with the player at left.

In addition, Fred took a number of other excellent pictures of the individual sculptures and decorative elements, and you can use the clickable thumbnails below to have a look at them:

|

Another block southeast and we turned towards the Tiber River, just at the corner where the Chiesa della Santissima Trinita di Pellegrini was located. Around 1540, Pope Paul III recognized a group called the Fraternity of the Holy Trinity of Pilgrims and Convalescents. Over the years, the group hosted pilgrims and cared for the convalescent poor, discharged from city hospitals. In 1558, Pope Paul IV assigned them the perpetual use of the church of San Benedetto in Arenula, and the fraternity bought a house near the church to be used as a hospital-hospice. The church was in bad shape, so the fraternity decided to build a new one. The first stone was laid in 1587 and the church consecrated in 1616. In subsequent centuries the parish and adjacent buildings continued to serve as a hospice for pilgrims, or as a hospital. The facade of the church has remained unchanged for over four centuries.

A couple of blocks further southwest on Via dei Pettinari and we crossed one of the avenues that parallel the Tiber (this one is Via Giulia, and this view looks north) to arrive at the eastern end of Ponte Sisto.

Ponte Sisto

|

The standout architectural feature of the bridge is the big, perfectly circular, hole in the central pylon that allows water to flow through when the river is high. This opening, nicknamed the "big eyeglass" by the Romans, has always been taken as the reference point for flood alarms, which come into effect as soon as the waters of the river in flood start flowing through it. (There is now an automated sensor to take the place of eyewitness reports.)

The bridge has been restored several times, most recently for the 2000 Jubilee. This restoration removed the iron and cast-iron superstructure built in 1877, giving it back its original appearance. The bridge is built of tuff faced with travertine; it is 300 feet long and 35 feet wide.

As we crossed the bridge, we got some nice views looking up and down the Tiber; you can use the clickable thumbnails below to see some of them:

|

On the far side of Ponte Sisto, there was a fountain where we were supposed to wait for Gaspar, but as we had a good deal of time until he was supposed to arrive, we decided to see if we could find some lunch in one of the little side streets south of the bridge. So we wandered down a few of them and eventually found a little cafe where we stopped for a snack. We went inside, got a table and had a little something to eat and drink while Frederico telephoned Gaspar. Then we walked back through the little streets to the monument to wait. On our little walk, Fred took some interesting photos that you might want to use the clickable thumbails below to have a look at:

|

When we got back to the fountain, Gaspar was still twenty minutes away, so I had time to wander around, take a few pictures, and read about the fountain.

The Fountain at Ponte Sisto

|

The city of Rome understood the needs and agreed to help the pontiff in his design of the Trajan aqueduct reopening. The work was completed in 1610, after much work was done outside of Rome to not only funnel water to the aqueduct but also to improve the supply of water in the rural areas.

The Ponte Sisto's fountain was originally located some distance further west, but this became inconvenient, and so in 1898 it was moved and positioned in the place where we see it today. The Latin inscription placed in the upper part of the facade commemorates this shift and "praises" the great work performed by Paul V, who brought water to the area. The fountain was designed by Giovanni Vasanzio, the fountain architect of the Borghese family.

The fountain consists of a series of roundabouts, which frame the large niche. The water falls from multiple levels, and then gathers in a large tank. On each of the columns, dragons projected two water jets. This representation is very symbolic, because the Dragon is one of the ancient Borghese's heraldic symbols. Today almost all jets are out of use, some are closed and others emit only a small stream of water. But of course modern water systems now supply the buildings in Rome.

The little square between the fountain and the Ponte Sisto was a very pleasant place to wait the few minutes it took for Gaspar to arrive. We just sat and chatted and watched people go back and forth on Ponte Sisto.

A Walk Along the Tiber River

The next bridge we came to was the Ponte Mazzini, and here, as was true with a good many of the bridges, there was a stairway down to the river.

|

The Florentine Pope Leo X de Medici initiated the architectural competition for a new church in 1518; luminaries no less than the painter and architect, Raphael, entered designs. A centralised church arrangement won, but various difficulties resulted in a change in the plan to a more traditional Latin cross plan. Work proceeded slowly. Leo died in 1523, and construction ground to a halt by the time of the Sack of Rome in 1527.

In 1559, Michelangelo was asked by Cosimo I de Medici, Duke of Tuscany, to prepare another design for the church, and construction began again in 1583, with the church completed (except for the facade) by 1620. The main façade, based on a design by Alessandro Galilei was not finished until 1734. And we think it takes a long time to get things done?

We kept following the avenue around past Ponte Milvio, a modern-looking, relatively unornamented bridge just before the river curved around eastward.

Ponte Vittorio Emanuele II

|

|

We took some additional pictures of this famous bridge, just south of Castel Sant' Angelo, and you can use the clickable thumbnails below to have a look:

|

|

|

Just before we crossed the bridge to end our walk (and visit Castel Sant' Angelo and The Vatican), I stopped on the north side of the bridge to survey the scene across the Tiber. I took four pictures that covered the area from Ponte Vittorio Emanuele II, around past Castel Sant' Angelo and ending with the Ponte Sant' Angelo. That panorama is below:

|

We have spent most of the day on an extremely enjoyable walk through Rome, and have seen many of the iconic places that to this time we've only seen in pictures, movies or TV shows. Now it's time to see two more.

Touring Castel Sant' Angelo

|

|

Once on the west side of the Tiber, we walked along the river towards the building that was actually the Mausoleum of Hadrian- Castel Sant' Angelo.

The towering cylindrical building known as Castel Sant' Angelo was initially commissioned by the Roman Emperor Hadrian as a mausoleum for himself and his family, and was once the tallest building in Rome. The mausoleum was erected between 130 and 139 as a decorated cylinder with a garden on top. Hadrian's ashes were placed here in 139, a year after his death, along with those of his wife Sabina, and his first adopted son, Lucius Aelius, who also died in 138. The remains of succeeding emperors were also placed here, the last recorded deposition being Caracalla in 217. The urns containing these ashes were probably placed in what is now known as the Treasury room, deep within the building.

|

Note first the Ponte Sant' Angelo, the bridge that crosses the Tiber directly south of the Castel; this bridge leads directly into the city of Rome from here and it is where we left Greg, Frederico and Gaspar to wait while we looked around inside the Castel. I have also marked the top of the Castel- the balcony from which we had such impressive views of Rome. This isn't really the top of the structure, of course; that position is occupied by the bronze statue of Saint Michael, and I have marked that location as well.

I'll mention below that the bronze replaced an earlier marble sculpture that was eventually moved to the open courtyard inside the building; I have marked that location as well.

Finally, I'll mention below that when the Castel was converted to a fortress, a way had to be found to allow the pope to get from the Vatican to the fortress in times of danger. The solution was to build a long, fortified walkway between the Vatican complex and the Castel. I have marked the point where this walkway enters the Castel at the upper right. (I thought at the time, when we looked down on this walkway from the balcony, that it was very reminiscent of those walkways in cities like Minneapolis that connect buildings at the second level, extending across streets to do so. We saw the same thing in Albany, New York. Of course, those walkways were built to shield pedestrians from the weather- which is particularly important in the winter. This walkway was to shelter the pope and other church officials from actual harm- quite a different issue.)

|

|

Greg, Frederico and Gaspar had all been in the Castel before, so they let us go on in while they waited on the bridge. (Fred used his incredible zoom to take that picture from the top of the castle.)

Much of the tomb contents and decorations have been lost since the building's conversion to a military fortress in 401 and its subsequent inclusion in the Aurelian Walls by Flavius Augustus Honorius. At that time, inside tunnels were modified, and the battlements were upgraded. (Much later, cannon were added.) The urns and ashes from the tombs were scattered by Visigoth looters during Alaric's sacking of Rome in 410, and (according to Procopius) the original decorative bronze and stone statuary were thrown down upon the attacking Goths when they besieged Rome in 537. Below are clickable thumbnails you can use to see some of the fortress-like aspects of the Castel:

|

Only a small amount of what we saw in the Castel during our walkthrough was part of the original structure. The historian Vasari wrote that many of the elements- structural and decorative- of the fortress were used elsewhere in Rome as well as at Saint Peter's.

|

The popes converted the structure into a castle, beginning in the 14th century; Pope Nicholas III connected the castle to St Peter's Basilica by a covered fortified corridor called the Passetto di Borgo. The fortress was the refuge of Pope Clement VII from the siege of Charles V's Landsknechte during the Sack of Rome (1527), in which Benvenuto Cellini describes strolling the ramparts and shooting enemy soldiers (with arrows, of course).

|

A regal apartment with a reception room, more than ten rooms, a library, corridors and staircases was created in the central part of the building, with a loggia opening onto Ponte Sant' Angelo, the Tiber and Rome. The rooms were all lavishly decorated with tasteful frescoes and the apartment boasted two loggias, placed opposite each other, known as "the Loggias of Paul II and Julius II," which still offer one of the most charming views of the city. Along the walls of the loggia were a series of sculpted heads inset in small niches; I do not know who they were, but you can see a couple of them here and here.

|

The works carried out in the apartment of Paul III took four years, and were completed in 1548. The decoration of the Castel was created in the light of ancient Roman art; each room is linked to the figure or theme it is dedicated to, with scenes fitted in between incomparably imaginary grotesques. The organization and working methods were innovative; each major artist or architect acted independently, assisted by five or six co-workers. They were responsible for their individual rooms and carried out that work with the assistance and creative ideas of their own teams. There are tours available that visit some of the individual rooms, but we did not have the time to take them (and they had to be booked in advance in any event).

|

There is a story behind the sculpture of the Archangel Michael atop the Castel. Legend holds that the Archangel appeared atop the mausoleum, sheathing his sword as a sign of the end of the plague of 590, and that this is where the castel got its present name. A less charitable (but probably more true) version of the legend was that during a prolonged season of the plague, Pope Gregory I heard that the populace, even Christians, had begun revering a pagan idol at the church of Santa Agata. A vision urged the Pope to lead a procession to the church. Upon arriving, the idol miraculously fell apart with a clap of thunder. Returning to St Peter's by the Aelian Bridge, the Pope had another vision of an angel atop the castle, wiping the blood from his sword on his mantle, and then sheathing it. While the Pope interpreted this as a sign that God was appeased, this did not prevent Gregory from destroying more sites of pagan worship in Rome.

The Papal state also used Sant'Angelo as a prison; Giordano Bruno, for example, was imprisoned there for six years. Another prisoner was the sculptor and goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini. Executions were performed in the small inner courtyard. As a prison, it was also the setting for the third act of Giacomo Puccini's Tosca; the eponymous heroine of the opera leaps to her death from the Castel's ramparts. Decommissioned in 1901, the castle is now a museum, the Museo Nazionale di Castel Sant'Angelo.

|

|

|

The views out across Rome from the top of the Castel Sant' Angelo were really impressive, as were the views of the Vatican itself.

|

To view the slideshow, just click on the image at left and I will open the slideshow in a new window. In the slideshow, you can use the little arrows in the lower corners of each image to move from one to the next, and the index numbers in the upper left of each image will tell you where you are in the series. When you are finished looking at the pictures, just close the popup window.

Before we left the top battlement, Fred created a panorama of the view from here of the city of Rome, and I have put that panorama below:

The View of Rome from Castel Sant' Angelo |

We made our way back down through the Castel to come out again at the Ponte Sant' Angelo where Greg, Frederico and Gaspar were waiting. Then we headed off down the street to our last stop for the day- The Vatican.

A Visit to Saint Peter's and Vatican City

|

From Castel Sant' Angelo, we headed west directly towards St. Peter's Basilica following the broad avenue that connects the two- Via della Conciliazione. Fred happened to be walking a bit ahead, and got a picture of the rest of us as we left the Castel. As you can see on the aerial view, while we were walking on the street, had we been a pope, we could have been using the fortified walkway a block north of us. (Actually, I rather doubt that this walkway is much used now, what with the Popemobile and all.) But as we walked along, we could see the walkway a block north of us. Fred used his zoom to get a nice closeup of the elevated path.

When we got to within a couple of blocks of St. Peter's Square, Greg, Frederico and Gaspar decided to stop for a coffee at one of the little cafes on the north side of the street. (Actually, I believe this was Frederico's 4th coffee of the afternoon.) Just before Fred and I continued on to St. Peter's, I got a picture looking back towards the Castel along Via della Conciliaziore.

Saint Peter's Square

|

|

Bernini had to work under the constraint of existing structures. For example, the huge Vatican Palace crowded the space to the right of the basilica's façade; these structures needed to be masked without obscuring the papal apartments. There was already an obelisk in the center and a single fountain to one side of it. For symmetry, he eventually matched the fountain on the other side. The largest portion of the area is actually an ellipse, the the fountains became its foci. Between this ellipse and the Basilica itself is a trapezoidal piazza. This shape, piazza, which creates a heightened perspective for a visitor leaving the basilica and has been praised as a masterstroke of Baroque theater, but it was largely a product of site constraints.

|

I'd like to include a few more pictures we took of these amazing twin colonnades, so you can use the clickable thumbnails below to have a look at them:

|

|

It was moved to its current site in 1586 by the engineer-architect Domenico Fontana under the direction of Pope Sixtus V; the engineering feat of re-erecting its vast weight took well over a year. The Vatican Obelisk is the only obelisk in Rome that has not toppled since ancient Roman times. During the Middle Ages, the gilt ball on top of the obelisk was believed to contain the ashes of Julius Caesar. Fontana later removed the ancient metal ball, now in a Rome museum, that stood atop the obelisk and found only dust.

I must admit that the combination of the obelisk and the colonnades presents a view that is really spectacular.

The paving is varied by radiating lines in travertine, to relieve what might otherwise be a sea of cobblestones. In 1817 circular stones were set to mark the tip of the obelisk's shadow at noon as the sun entered each of the signs of the zodiac, making the obelisk a gigantic sundial's gnomon.

I found myself wishing, when I looked at these pictures, that I had constructed my own panoramic view of the square, but I realise that it would not have turned out well. This late in the day, the north colonnade was in deep shadow and the south in bright sunlight. The picture would have looked very odd (since the facade of the Basilica was also in shadow). If I had been here back towards noon, though, such a panorama might have turned out like this one:

Saint Peter's Square |

|

But this threw off the symmetry of the plaza, and so he commissioned a duplicate fountain to put at the south focus of the ellipse. I could see it across the plaza just before I went up to see the Basilica, and my route back out again brought me right by that south fountain. While I was gone, Fred took an interesting picture incorporating one of the fountains; have a look:

|

Saint Peter's Basilica

|

In Roman Catholic tradition, the basilica is the burial site of its namesake Saint Peter; tradition and some historical evidence hold that Saint Peter's tomb is directly below the altar of the basilica. For this reason, many Popes have been interred at St. Peter's since the Early Christian period. There has been a church on this site since the time of Constantine. Construction of the present basilica, replacing the Old St. Peter's Basilica of the 4th century, began on 18 April 1506 and was completed on 18 November 1626- covering the papacies of (not in this order) Julius II-III, Leo X-XI, Hadrian VI, Clement VII-VIII, Paul III-IV-V, Marcellus II, Pius IV-V, Gregory XIII-XIV, Sixtus V, Urban VII-VIII, Gregory XIV-XV and Innocent IX.