|

November 29-30, 1975: A Weekend in Los Angeles |

|

June 8-12, 1975: A Week in Toronto, Canada |

|

Return to Index for 1975 |

This fall, I thought about going on an actual vacation, and Tony had expressed interest in going somewhere as well. With the job I have, involving weekly traveling someplace as it does, I sometimes think that a vacation is being able to stay at home and not go anywhere. But really, even though we travel a lot, we don't have all that much time to see the sights, and of course we don't get to do installations or training in Yellowstone National Park or in the South Dakota Badlands.

So Tony Hirsch and I made plans to do a cross-country trip and trying to get to a goodly number of parks and points of interest as we could work in. Our furthest point would be San Francisco, where Greg had invited us to use his apartment as a pit stop along the way. Tony wanted to "camp out" on the trip, and he suggested that if we just took sleeping bags with us, we could just plop down in a park or campground; he has, apparently, done this before. He was looking for a vacation that involved few hotel nights and no air travel. My objective was to see the sights and, frankly, I thought that checking in to a motel for the night was fine.

We ended up doing some of both. When we happened to be somewhere where there was a secure, safe camping area, we took advantage of it, and when there wasn't, well, a motel wasn't an admission of failure. All in all, I think we both enjoyed the two weeks; I know I did. We had our difficulties, but we also got to see a very great deal.

We got to see so much, that to put all of it on a single album page would result in an unwieldly page that would take way too long to load. So this trip will be spread across multiple pages. At the top and bottom of each page for this "grand tour" vacation there will be a link to get to the next one (if appropriate) and to the previous one (if appropriate).

So get comfortable and come along with us on our trip from Chicago to San Francisco and back!

Chicago to the Badlands of South Dakota

|

We begin with the trip north up to Milwaukee on Interstate 94. That trip took about 90 minutes (although it would have been a good deal longer had this been a weekday). At Milwaukee, we continued on I-94, now heading west.

|

Folling I-94 west from Milwaukee took us over to Madison, Wisconsin, and there we picked up I-90. Actually, the two interstate highways become coterminus at that point, and both head northwest. About 20 miles further on, I-94 splits off and continues north to cross the country to the west through the northern tier, eventually ending up in Seattle. I-90 heads west to do the same thing, but end up in Portland, Oregon.

|

|

This is not actually the main channel of the Mississippi River here; the river at this point has a number of large and small islands in the middle of its channel, so the river doesn't have the appearance that it does at, say, St. Louis. In my picture, the bridge is actually crossing to the largest of the islands in the river, but it will be another mile before we cross the main channel and actually enter the state of Minnesota. I took another picture at this park (looking south this time) and then I took one more picture from the car as we crossed the river's main channel to enter Minnesota.

|

|

The first Europeans to see the site of La Crosse were French fur traders in the late 17th century, but the first written records are from the 1805 expedition led by Lt. Zebulon Pike. Pike called the area "Prairie La Crosse" after a game that the expedition saw being played by the Native Americans there. The first white settlement here occurred in 1841 when Nathan Myrick, a New York native, moved to the area to work in the fur trade; he established a trading post at this site, and a village soon grew up around it. In 1850, an Episcopal Church was establishd, and in 1856, the 2,000 residents incorporated La Crosse. With a railroad and vibrant lumber industry, the city grew steadily right up to the present.

|

From the Mississippi River and La Cross, we headed out into the Great Plains towards Rochester, Minnesota, and then a bit southwest from there to the town of Albert Lea. From there, we faced an almost 200-mile stretch of interstate heading just about due west, straight as the proverbial arrow, towards Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

|

|

Tony thought all we had to do was throw down our sleeping bags in any old rest area and get a free night's lodging. First off, these rest areas have absolutely no security, and I told Tony that even if we left all our valuables in the car, I would have to have the keys on me, so anyone could come along, force the keys from us, and take the car and everything. Secondly, Tony was getting over a cold and I think he knew that a night out in the cold and damp wasn't what he needed. I guess the deciding factor was that a posted sign said that no overnight camping was allowed. So we decided to press on.

|

By the time we got to Chamberlain, we'd driven about 725 miles and, counting stops, spent about twelve hours on the road. We weren't totally exhausted, but it was time to call it a day. We found a motel at the Chamberlain exit on the east side of the Missouri River and we spent the night. For dinner, we had roast beef sandwiches. (I was to reach "roast beef sandwich overload" some days hence.) In the morning, we headed off to cross the Missouri River. Before and while we did so I took a couple of pictures to record the event.

|

|

As you can see from the pictures above, the landscape has changed dramatically from what we saw in Wisconsin and eastern Minnesota. There, the landscape was forested, but now we are heading across the Great Plains, where grasslands are the norm.

|

(NOTE:

In one of life's odd coincidences, this would not be the last time I would visit Chamberlain; I would actually visit twice more. About seven years from now, I will meet a Catholic priest in Chicago, and we will become friends. While I will lose track of him for a while after I move to Dallas, Texas, in 1985, we will eventually reconnect in the mid-1990s, and talk occasionally. In 2000, his order will transfer him to San Antonio, Texas, and, by that time, I will have two very good friends living there and running a bed and breakfast. I will introduce him to that couple and, during his years in San Antonio, the three of them will become fast friends. He will eventually be transferred to Green Bay, Wisconsin, and then, some years later, to Chamberlain. I will visit him once there around 2010, and then, a couple of years later, when he is again transferred back to San Antonio, I'll come up to Chamberlain and help him move. That trip here will, I strongly suspect, be my last visit to the area.)

As we headed west, the landscape seemed to get flatter and flatter, and soon even the rolling hills around the Missouri River had disappeared. They wouldn't return until we got to the Badlands.

|

|

Badlands National Park

|

We found the turnoff onto South Dakota Highway 240 with no problem; the exit for the east entrance to the Badlands National Monument was well-marked. When we got to the Visitor Center, we found that there was a park drive we could take that would continue west and eventually bring us back to Interstate 90, so that became our plan.

|

The Badlands Wilderness, which covers about 100 sq mi of the monument, is a designated wilderness area, and is one site where the black-footed ferret, one of the most endangered mammals in the world, was reintroduced to the wild. The South Unit, or Stronghold District, includes sites of 1890s Ghost Dances, a former United States Air Force bomb and gunnery range, and Red Shirt Table, the park's highest point at 3,340 feet.

Badlands National Monument was authorized by Congress in 1929, but the monument was not established until 1939. (Badlands will be redesignated a national park in 1978.) The Ben Reifel Visitor Center was constructed for the monument in 1957–58. The park also administers the nearby Minuteman Missile National Historic Site.

For 11,000 years, Native Americans have used this area for their hunting grounds, and their descendants live today in North Dakota. Archaeological records combined with oral traditions indicate that these people camped in secluded valleys where fresh water and game were available year-round. Eroding out of the stream banks today are the rocks and charcoal of their campfires, as well as the arrowheads and tools they used to butcher bison, rabbits, and other game. Homesteaders moved into South Dakota in the late 1800s, and what happened to the Native Americans was a tragedy. Their desperation led many to follow the Indian prophet Wovoka and conduct the "Ghost Dance". The prophet's ideas led to a continuing struggle, the climax of which came in late December, 1890, near Wounded Knee Creek, when US soldiers attempted to disarm the Indians. Gunfire erupted, and when it was over, 300 Indians and 30 soldiers were dead.

|

I could take the time to compare some of the photos we took today to those I took on subseqent visits to Badlands National Park, but if you are interested in those kinds of details, and haven't already done so, you can have a look at the album pages from 2006 and 2013; we visited the Badlands in both of those years.

What I would like to do on this page, though, is supplement the narrative I wrote for the slides (from which these pictures have been created) with some general information about the landscape that you are looking at, even if I don't take the time to tell you the name of each of the formations or areas of the park that I photographed.

|

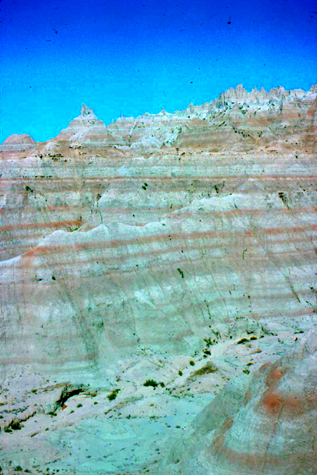

Take a look at the picture at left that I took from an overlook a mile or so east of the east Visitor Center. You can easily see that the rock formations were deposited in layers. The layers are composed of tiny grains of sediments such as sand, silt, and clay that have been cemented together into sedimentary rocks. The sedimentary rock layers of Badlands National Park were deposited during the late Cretaceous Period (67 to 75 million years ago) throughout the Late Eocene (34 to 37 million years ago) and Oligocene Epochs (26 to 34 million years ago).

Different environments— sea, tropical land, and open woodland with meandering rivers— caused different sediments to accumulate here at different times. The layers similar in character are grouped into units called formations. The oldest formations are at the bottom and the youngest are at the top, illustrating the principle of superposition.

The lighter-colored Sharps Formation was deposited from 28 to 30 million years ago by wind and water as the climate continued to dry and cool. Volcanic eruptions to the west continued to supply ash during this time. Today, the Brule and Sharps form the more rugged peaks and canyons of the Badlands. A thick layer of volcanic ash known as the Rockyford Ash was deposited 30 million years ago, forming the bottom layer of the Sharps Formation. The Rockyford Ash is a distinctive marker bed used in geologic mapping.

The tannish brown Brule Formation was deposited between 30 and 34 million years ago. As the climate began to dry and cool, the forest gave way to open savannah. Bands of sandstone interspersed among the layers were deposited in channels and mark the course of ancient rivers that flowed from the Black Hills. Red layers found within the Brule Formation are fossil soils called paleosols.

The greyish Chadron Formation was deposited between 34 and 37 million years ago by rivers across a flood plain. Each time the rivers flooded, they deposited a new layer on the plain. Alligator fossils indicate that a lush, subtropical forest covered the land. Most fossils found in this formation are from early mammals like the three-toed horse and the large titanothere. The sea drained away with the uplift of the Black Hills and Rocky Mountains, exposing the black ocean mud to air. Upper layers were weathered into a yellow soil, called Yellow Mounds. The mounds are an example of a fossil soil, or paleosol.

The black Pierre Shale was deposited between 69 and 75 million years ago when a shallow, inland sea stretched across what is now the Great Plains. Sediment filtered through the seawater, forming a black mud on the sea floor that has since hardened into shale. Fossil clams, ammonites, and sea reptiles confirm the sea environment.

|

|

Above are two more pictures we took along our drive the afternoon where you can see formations that illustrate the process of deposition, where the rocks are laid down stratum by stratum.

The other formational technique is, of course, erosion- which began in the Badlands about 500,000 years ago when the Cheyenne River captured streams and rivers flowing from the Black Hills into the Badlands region. Before 500,000 years ago, streams and rivers carried sediments from the Black Hills building the rock layers we see today. Once the Black Hills streams and rivers were captured, erosion dominated over deposition. Modern rivers cut down through the rock layers, carving fantastic shapes into what had once been a flat floodplain. The Badlands erode at the rapid rate of about one inch per year. Evidence suggests that they will erode completely away in another 500,000 years, giving them a life span of just one million years. Not a long period of time from a geologic perspective.

Here are two pictures that include formations created by both wind and water erosion:

|

|

A great many fossils are being continually unearthed in the Badlands, and many of these are sea creatures, consistent with the belief by geologists that this entire area was once under water, being part of the once great Inland Sea that covered the central part of North America. When you look out across the broad lowlands from the park road, it is easy to imagine that there was once an immense shallow sea here.

|

|

Here are the last two pictures I took in the Badlands before we reached the intersection of the park road and the highway that led north to Wall, South Dakota, and back to Interstate 90:

|

(Picture at left) This is a cliff face quite near the park road, and while they are a bit faint, you can see the large number of banded layers, indicating that these hills were laid down in successive layers over an extremely long period. You can see the dry streambed at the base of the cliff.

(Picture at right)

|

|

Mount Rushmore

|

From there, we found signs directing us to Mt. Rushmore.

Mount Rushmore National Memorial is centered around a sculpture carved into the granite face of Mount Rushmore in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Sculptor Gutzon Borglum created the sculpture's design and oversaw the project's execution from 1927 to 1941 with the help of his son Lincoln Borglum. The sculpture features the 60-foot heads of Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln. The four presidents were chosen, respectively, to represent the birth, the growth, the development, and the preservation of the United States. The memorial park covers 1,300 acres at an average elevation of about one mile above sea level.

I'm going to show you an aerial view of the National Memorial below, but remember that the aerial view is the one available to me as I am creating this page in 2019. As you might expect, the Memorial facilities have changed a great deal since our visit today.

|

But beginning in 1988, a ten-year project was undertaken to complete renovate and replace the existing visitor facilities, as the old ones had become very crowded with the 1.4 million visitors annually. This project was completed in 1998, and the next time I visited there was a new, large museum, a theatre, various shops, two restaurants, and, most importantly, a huge multi-story parking structure to handle the million or so cars that drove over from Keystone every year.

A new overlook was also constructed, and additional walking trails were developed to give visitors different views of the memorial. All in all, I recall it being like night and day. The visitor center of 1975 was almost entirely replaced, although the ranger HQ, which was in a smaller, older, redwood building near the restaurant, still exists today (now used as a maintenance and administrative building).

|

|

But probably the most famous (and most extensive) use of the Memorial was in Alfred Hitchcock's 1959 movie North By Northwest. In the climactic chase scene, Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint dangle from the faces in their attempt to escape pursuers. Of course, studio mockups were interspersed with actual footage to create the realistic illusion. But the Visitor Center facilities were also featured a bit earlier in the movie.

In the clip at right, Cary Grant and Leo G. Carroll begin a scene purportedly on the observation platform, although that part of the scene was a technical tour-de-force as actual photographs were used for the background. But, as near as I can find out, they did use external shots around the visitor center, showing the old parking area, the restaurant, and one of the other old buildings that we saw today.

Of course we took some pictures here- both inside the Memorial and also from the road we took when we left, which gave us a kind of profile view of the Memorial. I have marked that location on the aerial view above.

|

South Dakota historian Doane Robinson is credited with conceiving the idea of carving the likenesses of famous people into the Black Hills region of South Dakota in order to promote tourism in the region. In 1924, Robinson persuaded sculptor Gutzon Borglum to travel to the Black Hills region to ensure the carving could be accomplished.

The original plan was to make the carvings in granite pillars known as the Needles. However, Borglum realized that the eroded Needles were too thin to support sculpting. He chose Mount Rushmore, a grander location, partly because it faced southeast and enjoyed maximum exposure to the sun.

Borglum said upon seeing Mount Rushmore, "America will march along that skyline." Borglum had been involved in sculpting the Confederate Memorial Carving, a massive bas-relief memorial to Confederate leaders on Stone Mountain in Georgia, but was in disagreement with the officials there. Robinson wanted this sculpture to feature American West heroes such as Lewis and Clark, Red Cloud, and Buffalo Bill Cody, but Borglum decided that the sculpture should have broader appeal and chose the four presidents.

US Senator from South Dakota Peter Norbeck sponsored the project and secured federal funding; construction began in 1927, and the presidents' faces were completed between 1934 and 1939. Gutzon Borglum died in March 1941, and his son Lincoln took over as leader of the construction project. Each president was originally to be depicted from head to waist, but lack of funding forced construction to end on October 31, 1941 (with no fatalities). Sometimes referred to as the "Shrine of Democracy", Mount Rushmore attracts more than a million visitors annually.

|

|

The carving of Mount Rushmore involved the use of dynamite, followed by the process of "honeycombing", a process where workers drill holes close together, allowing small pieces to be removed by hand. In total, about 450,000 tons of rock were blasted off the mountainside. The image of Thomas Jefferson was originally intended to appear in the area at Washington's right, but after the work there was begun, the rock was found to be unsuitable, so the work on the Jefferson figure was dynamited, and a new figure was sculpted to Washington's left.

The Chief Carver of the mountain was Luigi del Bianco, artisan and headstone carver in Port Chester, NY. Del Bianco emigrated to the U.S. from Friuli in Italy, and was chosen to work on this project because of his remarkable skill at etching emotions and personality into his carved portraits. In 1933, the National Park Service took Mount Rushmore under its jurisdiction, and the faces were dedicated individually, as they were completed. The entire project cost about a million dollars.

|

|

Both Tony and I thought that Mt. Rushmore was inspiring; I'd seen pictures, of course, but there was nothing to compare to seeing it in person. Both of us used those telescopes on the observation platform to get a good look at the faces, and we also had a soda in the restaurant before we left.

|

We continued west on the Interstate to Sheridan, Wyoming, where we turned more west on US 14 and up into the Bighorn National Forest.

|

|

We pushed on, and soon began climbing steadily. At Sheridan, we turned west into the National Forest, and just inside found a secluded turnoff where we decided to spend the night. This suited me somewhat better, for we were able to pull the car into a deserted parking area and pitch our sleeping bags right next to the car, laying things out in its headlights. And it was sandwiches, chips, and sodas for dinner. In retrospect, I can see that I would have enjoyed this trip a great deal more, and would have been willing to camp out much more if we had only had a tent. As we moved West, into crowded camping areas, it was difficult for me to just pick a sleeping spot out in the open, with people walking round about, and there were times when all the campsites were full. Being novices, we soon found that it isn't allowed to just camp anywhere. I prefer a shower every day, but not having one that often is the feature, not the bug (to use a phrase from the present).

If you are ready to see what beautiful sights we'll see next, just click the button below:

|

November 29-30, 1975: A Weekend in Los Angeles |

|

June 8-12, 1975: A Week in Toronto, Canada |

|

Return to Index for 1975 |