|

October 26, 2018: Paradise Pond B&B and Our Trip Home |

|

October 24, 2018: Historic Chimayo and Ojo Caliente |

|

Return to the Index for Our Trip to New Mexico |

Today, we are going to have a full day, and we were gratified that when we awoke we could see that aside from some morning fog, the weather promised to be quite good. Given the morning fog, we will first visit Los Alamos, and then explore the many attractions of the Jemez Mountains, including Bandelier National Monument, Valle Grande, Las Conchas, and Tsankawi. Fred and I have done each of these attractions before, most recently in 2009, but this will be the first time Guy has explored these interesting areas.

A Visit to Los Alamos

From the Paradise Pond B&B, we headed through Espanola to Highway 285, and then took that south to pick up the road towards Los Alamos and the Jemez Mountains. We have been on New Mexico Highway 502 numerous times on our hiking trips to this area, and were familiar with it. As we got closer to Los Alamos (and higher into the mountains), we could see that there was still some fog that needed to burn off before the sunshine would reach into the valleys.

|

The road climbs steeply to get into Los Alamos, so there was plenty of mountain scenery as we came up into town on Central Avenue:

|

Los Alamos (from the Spanish for "the cottonwoods" or "the poplars") is recognized as the birthplace of the atomic bomb— the primary objective of the Manhattan Project conducted at the Los Alamos National Laboratory during World War II. The town is located on four mesas of the Pajarito Plateau, and has a population of some 12,000. It maintains its sense of history, but has become a gentrified mountain town with many restaurants, galleries, and shops- many of which cater to the thousands of tourists that visit the town year-round.

|

Fuller Lodge was the main building of a private ranch school for teen boys from 1917 until 1943. In late 1942, the building and surrounding area was purchased by the US Army for the Manhattan Project, and eventually turned into Los Alamos National Laboratory and the county of Los Alamos. Today, the Lodge is home to the Fuller Lodge Art Center, with many additional areas available for special events or just visiting. Fuller Lodge is also one of the stops on the Historic Walking Tour of Los Alamos.

We found a parking place in the small lot on the west side of the building, walked through it and around to the small museum that is attached to the historic building. From the parking area, we went into the lodge and found ourselves in what looked like a rustic ballroom with huge timber beams and a large fireplace at one end. It was a beautiful room; indeed, the entire structure, which looked like a very large, very ornate log cabin, was very impressive. We walked out the other side and around to the art museum.

|

|

Los Alamos is built on the Pajarito Plateau between White Rock Canyon and the Valles Caldera. The first settlers on the plateau are thought to be Keres speaking Native Americans around the 10th century. Around 1300, Tewa settlers immigrated from the Four Corners Region and built large cities but were driven out within 50 years by Navajo and Apache raids and by drought. Both the Keres and Tewa towns can be seen today in the ruins of Bandelier National Monument and Tsankawi (both of which we will visit today).

Homesteaders moved in in the early 1800s, building simple log cabins that they only lived in during warm weather (moving down into the Rio Grande valley in winter). Homesteader Harold H. Brook sold part of his land and buildings to Detroit businessman Ashley Pond II in 1917 which began the Los Alamos Ranch School, named after the aspen trees that blossomed in the spring. Los Alamos ambled slowly into the mid-20th century.

In 1942, during World War II, the Department of War began looking for a remote location for the Manhattan Project. The school was closed when the government used its power of eminent domain to take over the Ranch School and all the remaining homestead that same year. All information about the town was highly classified until the bombing of Hiroshima. Incoming material for the Project was intentionally mislabeled as common items to conceal the true nature of their contents, and any outbound correspondence by those working and living in Los Alamos was censored by military officials. At the time, it was referred to as "The Hill" by many in Santa Fe, and as "Site Y" by military personnel. The mailing address for all of Los Alamos was PO Box 1663, Santa Fe, NM. After the Manhattan Project was completed, White Rock was abandoned until 1963 when people began to re-inhabit and rebuild new homes and buildings. Today, the town is a haven for people who want to live in the mountains yet be near facilities and culture.

We spent a half hour or so inside the small art museum- which, as it turned out, had a lot of very nice stuff, representing both arts and crafts:

|

|

After spending some time in Los Alamos (and scoping out a few places we might keep in mind for dinner at the end of the day), the fog had pretty much disappeared, and so we headed off to Bandelier National Monument.

Bandelier National Monument

We spent quite a bit of time at Bandelier today; it, to us, is one of the gems of the American Southwest, and we wanted Guy to be able to appreciate it for as long as he wished.

Getting to Bandelier National Monument

|

First, it goes by the town of White Rock; just outside that town is the Tsankawi Trail (which we will do later on today) that takes the visitor up onto a mesa that was occupied for many centuries. Next, the road goes by the entrance to Bandelier NM (where we will stop first). It then climbs through beautiful forest to come out on the south side of Valle Grande- one of the largest calderas on earth.

The road then goes through the Jemez Mountains, passing numerous trails, waterfalls, and hot springs. It then turns south into a more arid landscape and passes through three or four very old pueblo settlements and a couple of much more modern wineries before coming to an end at Interstate 25 just north of Albuquerque. It is a highway that we have traveled numerous times in both directions, and I think that Fred and I have stopped, either by ourselves or with Greg, Ron, and/or Prudence, at just about every attraction along it.

Today, the trip to the entrance to Bandelier took about thirty minutes, and we arrived in bright sunshine- certainly the best day we could have wished for.

Getting to the Bandelier National Monument Visitor Center

|

At the entrance station (which was unmanned with a sign requesting visitors to pay their entrance fees at the Visitor Center or the Campground), we stopped to take a few pictures. Here are some of them:

|

The Visitor Center is actually about three miles from the park entry off Highway 4, so after we'd taken our pictures we got back into the car and headed off down that road.

|

|

Bandelier was designated by President Woodrow Wilson as a National Monument on February 11, 1916, and named for Adolph Bandelier, a Swiss-American anthropologist who researched the cultures of the area and supported preservation of the sites. The National Park Service co-operates with surrounding pueblos, other federal agencies, and state agencies to manage the park. The monument has around a hundred thousand visitors each year.

|

In October 1976, roughly seventy percent of the monument was included within the National Wilderness Preservation System, and the Valles Caldera National Preserve (which will be our next destination today) adjoins the monument on the north and west, extending into the Jemez Mountains.

Much of this area was covered with volcanic ash (the Bandelier tuff) from an eruption of the Valles Caldera volcano 1.14 million years ago. The tuff overlays shales and sandstones deposited during the Permian Period and limestone of Pennsylvanian age. The volcanic outflow varied in hardness; the Ancestral Pueblo People broke up the firmer materials to use as bricks, while they carved out dwellings from the softer material.

This must have been a good place to live, as the valley looks green and fertile and the cliffs provide shelter for the people living there; indeed, humans have lived in this area for at least 10,000 years, although permanent settlements date to only the 12th century. By the mid-16th century, the area was largely abandoned as people moved closer to the Rio Grande. The distribution of basalt and obsidian artifacts from the area, along with other traded goods, rock markings, and construction techniques, indicate that its inhabitants were part of a regional trade network that included what is now Mexico. Spanish colonial settlers arrived in the 1700s, and a local pueblo brought Adolph Bandelier to visit the area in 1880. Looking over the cliff dwellings, Bandelier said, "It is the grandest thing I ever saw."

We will be doing all the trails on the valley floor here at Bandelier today. We won't be doing any of the backcountry trails, nor will we be doing the falls trail down to the Rio Grande. The three trails that we will be doing are shown on this aerial view of the Bandelier valley floor:

I think that another resource you might find informative to follow us along on our walks today would be the official park map from the brochure that we picked up in the Visitor Center.

|

As I've said, Fred and I have been here twice before- once with our friend Greg in 1992, and once with our friends Ron and Prudence in 1998. Each time has been very, very enjoyable, and we have never tired of exploring the ruins. I doubt that today will be any different. (I might also recall that of all the place we've been multiple times, we have always had perfect weather here at Bandelier.)

Inside the Visitor Center, we not only picked up the park map, but we also had a quick look at the many exhibits about the site's inhabitants, including Ancestral Pueblo pottery, tools and artifacts of daily life. Two life-size dioramas demonstrated Pueblo life in the past and today. Also featured were contemporary Pueblo pottery pieces, 14 pastel artworks by Works Progress Administration artist Helmut Naumer Sr, and wood furniture and tinwork pieces created by the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Depression.

To complete a short history of Bandelier, we can note that after his first visit in 1880, Adolph Bandelier performed a great deal of research on the area, and based on that research and his documentation, there was support for preserving the area and President Woodrow Wilson signed the legislation creating the monument in 1916. Supporting infrastructure, including a lodge, was built during the 1920s and 1930s. The structures at the monument built during the Great Depression by the Civilian Conservation Corps constitute the largest assembly of CCC-built structures in a National Park area. The group of 31 buildings illustrates the guiding principles of National Park Service- rustic architecture based on local materials and styles. In recognition, Bandelier has also been designated as a National Landmark District.

During World War II the monument area was closed to the public for several years, not because tourist visitation dropped off sharply, but because the lodge and the other buildings were being used to house personnel working on the Manhattan Project at nearby Los Alamos to develop the atomic bomb.

The Main Loop Trail

|

We began by walking from the Visitor Center to the actual trailhead for the Main Loop Trail as we read from the trail guide.

|

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

As Ancestral Pueblo people traveled across the Pajarito (pa-ha-REE-toe, “little bird” in Spanish) Plateau they must have moved in and out of Frijoles Canyon. As we walked along this trail we could imagine standing on the rim of the canyon. The quiet air would bring the gentle murmur of the creek to our ears. In spring the freshly sprouted green of the trees and shrubs near the water is in marked contrast to the darker green of the piñon-juniper woodlands on the mesatops. Undoubtedly the plentiful and diverse natural resources made this an ideal place to settle.

|

|

Frijoles Canyon lies in an area where numerous volcanic eruptions have shaped the landscape. Other local volcanic activity provided harder stones such as obsidian and basalt. The Ancestral Pueblo people used these materials for tools and as trade items.

|

The path was skirting the cottonwoods along the watercourse, but the views to our right of the cliff face along which the trail would eventually take us were unobstructed:

|

|

|

|

Native plants played an important role in Ancestral Pueblo life. Even with the transition to agriculture, extensive use of native plants continued. Ponderosa pines, growing tall and straight, provided the ceiling beams, also called vigas, for homes. Yucca, with its broad stiff leaves and large white flowers, offered fibers for sandals, baskets, and rope. The Ancestral Pueblo people made an all-purpose soap from yucca roots and ate the tasty yucca flowers. Knowledge of plant uses was passed down through the generations through oral traditions, which continue today.

The next stop along the Main Loop Trail came as the trail curved over towards the cliffs and began to traverse the open valley away from Frijoles Creek; that stop was at "the Big Kiva".

|

|

When in use, this kiva would have been covered by a roof made of wood and earth. Six wooden pillars supported the roof. The short upright logs on the kiva floor show the relative positions of these pillars. You would have entered the kiva using a ladder through an opening in the roof. The roof would have been hard plastered with mud to support people walking on it. Imagine climbing down the ladder into a darkened room, flickering torches offering the only light, people sitting on the floor and along the walls. This was a special place where important decisions and knowledge were communicated. The kiva was the community’s heart and center.

|

There is no evidence revealing the purpose of the rectangular holes in the floor. Thin pieces of wood covered similar features excavated in other kivas, suggesting possible use as foot drums. Other possible uses include storage or for the sprouting of seedlings in the early spring.

Notice the two different layers in the stone wall. The inner layer may have been a complete wall. It exhibits much finer stonework than the coarse outer wall. This suggests the kiva may have been rebuilt after its initial construction.

As we crossed the open area between the Big Kiva and Tyuonyi, we read about how the Puebloan people probably used this open area, which was conveniently near the watercourse of Frijoles Creek.

|

|

By 1200 AD Ancestral Pueblo people began to practice agriculture on the Pajarito Plateau and in Frijoles Canyon. Small fields, some in the canyon and many on the surrounding mesas, were planted with corn, beans, and squash. The Ancestral Pueblo people used numerous techniques to take advantage of available moisture. These included planting seeds deep into the ground where moisture is stored by the soil, grouping of plants to provide shade and support to each other, and mulching plants with water-retaining pumice and rocks. Check dams, terracing,and waffle gardens provided methods for controlling water flow. (Waffle gardens are constructed by forming small depressions surrounded by a low earthen wall. Seeds are planted within the cavity.)

Since summer rainfall is often localized, the people scattered their fields across the landscape in the hopes that some would receive the necessary rainfall to produce a good harvest. Moving on, we came to the largest settlement here at Bandelier.

|

|

One to two stories high, Tyuonyi contained about four hundred rooms and housed approximately 100 people. A central plaza contained three kivas; you can have a look at my picture of one of the largest. Access to the village was through a single ground-level opening.

The pathway went right through the ruins of the village, and here are more views of it (one of which was taken from the cliff face a bit later on):

|

|

|

Some people say that Frijoles Canyon was the dividing line between two language groups. Today Tewa (TAY-wah) speakers live to the north of the canyon and Keres (CARE-ace) speakers to the south. Some Keres speakers say the name Tyuonyi means "a place of meeting" or "treaty".

|

I would like to include here a picture of Tyuonyi that was constructed by combining three images that Guy took from up on the cliff face; in the panorama, you can see the entirety of the village:

Tree-ring dating shows the construction of Tyuonyi began more than six hundred years ago; the caves were occupied at the same time. The choice to live in the caves or on the canyon bottom may have been based on family, clan custom, or maybe simply preference.

|

|

From here, we took the fork in the path over to the cliff face. Notice that the cave and cliff dwellings are located along the south-facing canyon wall. In the winter, that side gets the afternoon sun and is much warmer than the north-facing wall on the other side of Frijoles Creek. As we leave the flat bottom of the valley, here's a panoramic view of the walkway over to the cliff face:

|

|

|

|

Once we got up here to the cliff face, we were treated to expansive views to the south- down the valley towards the Rio Grande. There were also nice views across the valley to the southwest and the Frijoles River, and Guy asked me to use that backdrop and his phone to take a portrait of Guy at Bandelier. The trail continued around the rocks to the right where we got more nice views looking up and down the valley:

|

|

There were many holes in the tuff that we could see as we walked along. I am sure that not all of them were ancient; and I was pretty sure that not all of them were man-made. Weathering certainly played a role.

|

|

|

|

|

A short distance further on, the trail turned the corner of the rock face and we were looking down a long row of reconstructed buildings, many of them with ladders so we could go investigate.

|

|

|

The earliest evidence of a collection of dense settlements within Frijoles Canyon dates to the mid-1200s. However, it was not until the mid-1300s that large-scale construction of villages like Tyuonyi took place.

|

The views all along the cliff face, before we got to Talus House and Cave Kiva, were just spectacular. Here are some of them:

|

When you look at Talus House and the number of cavates it is easy to imagine a whole row of houses lining the canyon walls looking down on a cleared canyon floor. The voices of people coming and going from Tyuonyi and the hum of the bustle of daily life filled the densely populated canyon.

|

|

Climbing down out of the cliff dwelling, there were more great views of the cliff face and the Frijoles Creek valley. Here is a view looking back the way we've come, and here are two more great views looking out from the cliffside:

|

|

From the last dwelling, we are heading further along the cliff face and across a particularly treacherous part of the area- as a large number of boulders have either fallen or have always been where they are. Fortunately, a stairway with handrails has been installed (and here you can see Guy at the bottom of that stairway. Actually, there were two sections to this stairway, and behind Fred on those stairs is the entrance to Cave Kiva.

|

|

It was a lot of fun to climb the ladder into this cave, which, as you can see, was big enough to stand up in. There was a skylight in the ceiling but no windows. Here are some of the other pictures we took in this dwelling:

|

|

|

|

|

Walking along the face of the cliff, there were simply beautiful views in all directions.

|

|

|

|

|

Trade items were brought to Frijoles Canyon from distant places such as Mexico. These items included shells, special stones, live parrots as depicted in petroglyphs and feather remains, and worked goods such as copper bells. The exchange of ideas, as a by-product of trade and travel, is also evident in Bandelier. Rock markings may indicate that there was interaction between the Ancestral Pueblo people and people in Mexico. Construction techniques, such as those used in the Big Kiva, mirror those found in Colorado Plateau sites such as Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde.

|

|

There was a very long row of these dwellings up against the cliffs. Here are some really good views, of these dwellings, and some closeups of the viga holes:

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Ancestral Pueblo people were drawn to Frijoles Canyon by the abundance of resources found here. They led daily lives of hard work and family activities. Homes were built from the available stone, and children were raised generation after generation. For more than 400 years these places were filled with the sound of laughter, grief, and worship. What caused the people of Frijoles Canyon to leave a place they called home? Were the resources that had seemed so plentiful depleted? Did the game animals leave as the land was cleared for homes and fields? Did a major multi-year drought and repetitive crop failures empty the food storage rooms? Undoubtedly, the people left in response to a concurrence of events. When they left, the people of Frijoles Canyon moved south and east toward the Rio Grande and the modern pueblos where their descendents still live today.

|

|

Alcove House

|

Formerly known as Ceremonial Cave, this dwelling is located 140 feet above the floor of Frijoles Canyon. Once home to approximately 25 Ancestral Pueblo people, the elevated site is now reached by 4 wooden ladders and a number of stone stairs. In Alcove House, there is a reconstructed kiva and the viga holes and niches of former homes. Imagine climbing these ladders, carrying whatever supplies were needed, to this lofty home. If you look closely at the picture at left, you'll see a red-shirted person on one of the ladders; this should give the picture some scale.

Walking through the forest, we heard a good many animal sounds- not unusual since wildlife here is locally abundant. Deer and Abert's squirrels are frequently encountered in Frijoles Canyon. Black bear and mountain lions inhabit the monument and may be encountered by the backcountry hiker. A substantial herd of elk are present during the winter months, when snowpack forces them down from their summer range in the Jemez Mountains.

Notable among the smaller mammals of the monument are large numbers of bats that seasonally inhabit shelter caves in the canyon walls, sometimes including those of Frijoles Canyon near the loop trail. Wild turkeys, vultures, ravens, several species of birds of prey, and a number of hummingbird species are common. Rattlesnakes, tarantulas, and "horned toads" (a species of lizard) are occasionally seen along the trails.

About a half mile walk through the forest brought us to the base of the trail up to Alcove House. To get into Alcove House, one has to climb three sections of very steep ladders; we remembered this from our visit in 1992. At that time, Greg decided not to go to the top, so Fred and I went on our own.

Alcove House Trail |

First Staircase |

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

Before we headed up some stone stairs to the next ladder, Guy and Fred decided that they wouldn't make the trip all the way to the top, but would go back down to the valley floor and wait if I wanted to go ahead and climb to the top. I did want to repeat the visit from a quarter-century before (if only to see if Alcove House had changed much), so I asked if they might wait twenty minutes or so for me so I could go to the top. That was fine, and they headed back down. By the time they got to the bottom, I had first traversed the trail worn into the rock and then a long set of stone steps that brought me to the base of the next ladder; you can see Fred's zoom picture of me that he took from the valley floor here.

|

Here are some other pictures taken from this second landing:

|

Finally, to get to Alcove House itself, I climbed the last ladder (just before some other folks were on their way down).

|

|

Before we have a quick look around Alcove House itself, I want to insert here two pictures that Fred took from the valley floor as I was coming up on my own. They will give you a better idea of how high up Alcove House and what it looks like as a whole. In the second picture, you can see me at the landing before the last ladder.

|

|

In Alcove House itself, I found it to pretty much match my memory of what it was like. I had recalled it being smaller, actually, but that's neither here nor there.

|

The whole area looks as if it was hollowed out by the inhabitants, although there might have been a natural shelf here to start with. I wondered about that, because the rock here seemed much tougher than the easily-worked tuff that we saw earlier.

The one difference I can really point out is that when I was here before, the kiva was open, and it had a ladder you could climb down to get inside the kiva itself (and we did that last time). Today, and I suspect permanently, the kiva has a cover on it, and that cover is locked. The Bandelier National Monument website indicated that this is just temporary while the "ceiling" of the kiva is being maintained, but for some reason I think that isn't actually the case. I'd bet that at some point in the past, someone got hurt climbing into or out of the kiva, and so for safety's sake that is no longer allowed.

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

I also took a few still pictures, including a good one of the closed kiva, and you can see those below:

|

That ended my visit to Alcove House, so I went back down the various ladders and stairways to rejoin Guy and Fred on the valley floor, and then we began the mile-plus walk back to the Visitor Center.

The Nature Walk: Alcove House to the Visitor Center

|

|

That slideshow is at left. You will see that some of the slides actually have two pictures; Guy, particularly, took lots of vertical shots, perhaps influenced by the fact that we were walking through an area of mostly tall trees. So I've often doubled up to reduce the number of individual slides.

To move from one slide show to the next, use the little "forward" and "backward" arrows in the lower corners of each slide. There are thirty-one slides in the show, and you can track your progress by referring to the index numbers in the upper left of each slide.

I hope you find the pictures to be a good representation of what we saw, although I can certainly point out the obvious: there is no substitute for being there.

Actually, about the only reasonable substitute for "being there" that I can offer are a couple of movies. I hope you will have a look at two of the best ones I made:

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

About the only disconcerting thing, considering that at a few spots along the walk I just sat down on a log to appreciate the serenity and beauty of the scenery around me, was that Guy came across another hiker on the trail. When we got back to the Visitor Center, we sat down to have a snack before heading off to Valle Grande:

|

|

The Valle Grande Caldera

A while ago, Guy painted a picture of Valle Grande for Fred and I as a gift; he did it from a photograph we had taken on our last trip through here. So we wanted to take Guy to see the actual caldera for himself.

|

Along the way, we were treated to many more of the bright yellow cottonwoods and to a variety of landscapes, including snow-covered mountains, cultivated hillsides and valleys, and forested mountains. Here are just a few examples of the scenery along Highway 4:

|

After about thirty minutes of driving from Bandelier, the highway came down out of the forested Jemez Mountains to come alongside a huge open area that looked like a huge, fairly regular, depression in the landscape- the Valles Caldera (locally, "Valle Grande").

|

The caldera and surrounding volcanic structures are one of the most thoroughly studied caldera complexes in the United States. Research studies have concerned the fundamental processes of magmatism, hydrothermal systems, and ore deposition. Nearly 40 deep cores have been examined, resulting in extensive subsurface data.

The human use of the Valles Caldera dates back to the prehistoric times: spear points dating to 11,000 years ago have been discovered. Several Native American tribes frequented the caldera, often seasonally for hunting and for obsidian, used for spear and arrow points. Obsidian from the caldera was traded by tribes across much of the Southwest. Eventually, Spanish and later Mexican settlers as well as the Navajo and other tribes came to the caldera seasonally for grazing with periodic clashes and raids. Later as the United States acquired New Mexico as part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, the caldera became the backdrop for the Indian wars with the U.S. Army. Around the same time, the commercial use of the caldera for ranching, and its forest for logging began.

|

The caldera became part of the Baca Ranch in 1876. The Bacas were a wealthy family given the land as compensation for the termination of a grant given to their family near Las Vegas, in northeastern New Mexico. This area, 100,000 acres, has since been through a string of exchanges between private owners and business enterprises. Most notably, it was owned by Frank Bond in the 1930s. Mr. Bond, a businessman based in nearby Española, ran up to 30,000 sheep in the calderas, significantly overgrazing the land and causing damage from which the watersheds of the property are still recovering.

|

Guy took two really good pictures of the caldera (in addition to the one at right). These are below:

|

The Valles Caldera Preservation Act of 2000 signed by President Clinton created the Valles Caldera National Preserve. The legislation provided for the federal purchase of this historical ranch nestled inside a volcanic caldera, with funds coming from the Land and Water Conservation Fund derived from royalties the US government receives from offshore petroleum and natural gas drilling.

|

The Dunigan family sold the entire surface estate of 95,000 acres and most of the geothermal mineral estate to the federal government for $101 million. As some sites of the Baca Ranch are sacred and of cultural significance to the Native Americans, 5,000 acres of the purchase were obtained by the Santa Clara Pueblo, which borders the property to the northeast. This include the headwaters of Santa Clara Creek that is sacred to the pueblo. On the southwest corner of the land 300 acres were to be ceded to Bandelier National Monument.

|

|

Valles Caldera is a resurgent dome caldera. After the initial caldera forming eruption here, the Redondo Peak resurgent dome was uplifted, a process that began around 1 million years ago. Smaller eruptions occurred from then to the most recent- about 60,000 years ago. The caldera and surrounding area continue to be shaped by ongoing volcanic activity.

|

This caldera and associated volcanic structures lie within the larger Jemez Volcanic Field. This volcanic field lies at the intersection of the Rio Grande Rift, which runs north-south through New Mexico, and the Jemez Lineament, which extends from southeastern Arizona northeast to western Oklahoma. The volcanic activity here is related to the tectonic movements of this intersection.

|

In the pictures you've seen so far, it may look as if the grass valleys have been mowed, and the trees on the hillsides may have also looked as if they'd been trimmed (there are few saplings and mature trees lack lower branches). All of this is due to heavy browsing by elk and cattle and because of frequent grass fires of human and natural origin which kill the lower branches on the Engelmann spruce, Douglas-fir and Ponderosa pine that populate the uplands around the grasslands dominating the bottoms of the calderas. Extreme cold in winter prevents tree growth in the bottoms of the calderas. The grasslands were native perennial bunch grass maintained by frequent fire before sheep and cattle grazing. Although the grass appears abundant, it is a limited resource. Its growing season is short; various grazing programs try to maintain it, but many thousands of wild animals also graze on this low-nutritional-value grass.

Guy was very interested to see Valle Grande, and we stayed at the overlook parking area for the better part of an hour. I want to conclude our visit with two more panoramic views- the first one taken by Fred and the second a composite picture I created from two individual pictures:

|

|

A Hike on the Las Conchas Trail

From Valle Grande, we wanted to take Guy a short distance further west to a neat trail that we have hiked before- the Las Conchas Trail.

|

|

There is actually not a lot say about the Las Conchas Trail- except that is one of the most beautiful trails in New Mexico- and that's saying a lot. There are many reviews and journal entries online written by people who've hiked the trail, and none that I ever found had a bad thing to say about the trail. The trail runs along, and crisscrosses, the East Fork of the Jemez River, and there are sturdy footbridges at each crossing. When we started out, Guy was snapping away; here are some of his initial pictures:

|

Right when we started out, Fred and Guy got a bit ahead of me because I stopped to make a movie at the trailhead, and then do another as I set off on the trail (where I will talk a good bit about the trail itself and our earlier visits). I hope you watch both of these movies, as they will give you a lot of background about the trail:

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

The trail begins on the west side of the narrow river as the trail goes along the treeline on the left and the river on the right. This part of the trail, accessible by almost everyone, is by itself a reason to stop here and at least hike a short distance of the trail.

|

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

Speaking of fallen logs, there were a number of them laying across the stream, and I am pretty sure that lots of folks walk across them not because they think they are part of the trail but more because its fun and they just want to see what's on the other side. In that last picture, you can see that people have worn a short trail on the other side going to that rock outcrop. A little ways further on, I took this picture looking back towards the trailhead.

|

As I said earlier, there were a number of footbridges on the trail as it criss-crossed the stream, and we stopped to take pictures at almost all of them. Here's a selection of those pictures:

|

When we began our hike, the weather was just beautiful. It was chilly, but it was sunny. It was cold enough that I thought it best to wear my jacket, and as the hike proceeded, I was glad I had. It seemed to get a bit colder, and it certainly was getting cloudier.

|

These rock outcrops lent a really neat element to the beauty of the trail and the narrow valley through which it wound, and of course we ended up taking quite a few pictures that featured these rocky pillars. You can see one behind Guy and I in the picture at left, and some more of them are below:

|

The Las Conchas Trail is one of those trails that doesn't really have a destination; one hikes this trail to experience the beauty of the surrounding terrain. The trail actually continues a few miles through the backcountry, and eventually ends in another trailhead and parking area further west on Highway 4.

|

|

From the furthest extent of our walk, I filmed a movie that talks about the extent of the trail and shows one of the footbridges that we crossed (obviously, the last one we crossed). I think this movie is pretty good, and you can use the player below to watch it:

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

So, we turned back to return to the parking area, beginning to wonder if it was going to rain before we got back. I took two more pictures on the way back, one of the trail through the trees, and one more of a section of the Jemez River. The interesting end to the hike was that we were about a hundred feet from the parking area when it actually began to sleet! It didn't seem cold enough, and at ground level I am sure it wasn't, but it must have been much colder a few thousand feet above us. Anyway, it was kind of interesting, but soon over. As we drove back east along Highway 4 to the Tsankawi Prehistoric Sites, the sleet stopped and the sun even began to peek through the clouds.

Exploring the Tsankawi Prehistoric Sites

From the Las Conchas Trailhead, we headed back east to visit the last thing we wanted to show Guy today, and another place thet Fred and I have been, the Tsankawi Prehistoric site.

|

Tsankawi is actually a detached portion of Bandelier National Monument; if you visit Bandelier and pay an entry fee there, you can also visit the Tsankawi site (there is an honor system at Tsankawi). At the site there is a self-guided 1.5-mile loop trail providing access to numerous unexcavated ruins, caves carved into soft tuff, and petroglyphs. We picked up a trail guide, available at the entrance, and I'll be using some information from that to help describe the pictures we took.

Tsankawi (san-KAH-wee) was built by ancient Pueblo Indians sometimes known as the Ancestral Pueblo People. Archeological evidence indicates that Tsankawi may have been constructed in the 15th century and occupied until the late 16th century- toward the end of the Rio Grande Classic Period. It was occupied by Ancestral Pueblo people. Dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) indicates that a severe drought occurred in the late 16th century. Traditions at a number of nearby Tewa Pueblos, including San Ildefonso Pueblo, Santa Clara Pueblo, Pojoaque Pueblo, and Tesuque Pueblo claim ancestral ties to Tsankawi and other nearby pueblo sites.

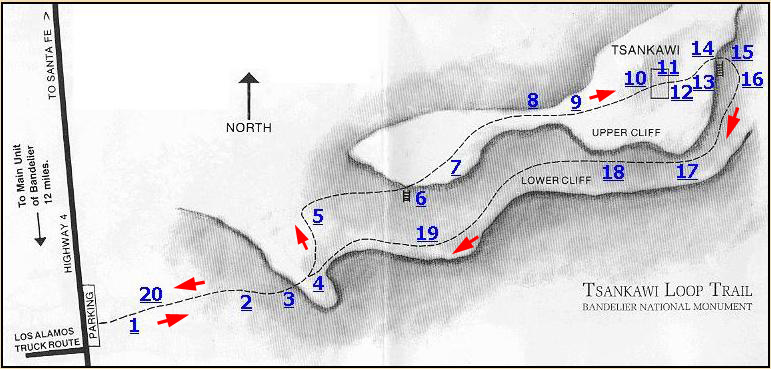

To help you follow us along on our 90-minute hike, I have put an aerial view of the Tsankawi Mesa below, left, and a copy of the trail diagram from the guide to its right. I've tried to make them both about the same scale so that you can see where the trail (marked on the aerial view) crossed the actual landscape.

|

|

The Ancestral Pueblo people built homes of volcanic rock and adobe (mud), cultivating fields in the open canyons below. Their daily lives of hard work and family left their mark on the land. Low stone walls, carved drawings in the rock faces, and fragments of utilitarian objects are important artifacts left by the Ancestral Pueblo people. For the people of San Ildefonso Pueblo these sites represent much more than interesting glimpses into the past. Although the present-day Pueblo people do not occupy Tsankawi on a daily basis, the site serves an important role in their spiritual lives and provides both tangible and intangible connections with traditions passed down through generations. Tsankawi is a timeless place where echoes of a distant past intersect the present. Parents raised children here. Together they fought the ravages of nature to survive in these now vacant rooms and along these dusty trails.

I want you to feel that you are walking along with us on this hike, so I am going to reproduce most of the trail map and guide here, to describe the pictures that we took along the way. You may not want to read all the detail, but, then again, you might have an interest in archaeology, and be curious as to the history of this place.

|

Here again is the trail map that we found in the trail guide that we carried with us. On the trail map, you can find twenty underlined numbers; these are the various marked trail stops. To follow us along the trail, just click on the numbers in any order you wish. When you do, you'll be taken to the description of that trail stop and the pictures we took near it. When you are done with that trail stop, you will find a link that will bring you back here. You can also simply scroll down the page and look at the stops in sequence.

If you have chosen the method of coming back to this map after each stop, and you are done with all the trail stops that you want to look at, you can continue with the days activities after Tsankawi by clicking here.

|

The prehistoric people of Tsankawi (sah-kah-WEE) were totally dependent on their environment. Everything they possessed- their homes, clothing and food- came directly from "Mother Earth".

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

The Ancestral Pueblo people may have found Tsankawi a congenial place to live, but after many years of occupancy they moved on. Although they respected the Earth and her gifts, they had to use some resources in order to stay alive. In this sparse, arid environment, their needs were too great to be sustained indefinitely. Archaeologists tell us that the ancestral Pueblo people left Tsankawi as a result of a decrease in rainfall, along with the depletion of important natural resources such as firewood, and soil exhaustion from centuries of farming. Many Pueblo Indian legends tell of groups moving from place to place. Moving on after several generations may have been an expected part of life.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here, or simply scroll down for our next stop.

|

Juniper, pinon, rabbitbrush, yucca, four-winged saltbush, and mountain mahogany are common along this trail. Ancestral Pueblo people depended on many of these plants for food, medicine, dyes, spices, and tools. Some of these plants are still used for the same purposes in contemporary pueblos.

The climate has changed little since the time when Indians were living here. The environment is dry, averaging about 15" of precipitation each year, and frost or freezing can occur into mid-May. Yet these people were able to develop an agricultural way of life. They made expert use of resources such as native plants, wildlife, and various types of stone.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here, or simply scroll down for our next stop.

|

The type of plants here are typical of piñon-juniper woodlands found in many areas of the Southwest where ancestral Pueblo people settled. Plants adapted to dry conditions are usually slow-growing and not very tall, thus the name "pygmy forest". Ponderosa pines, common at higher, wetter locations, are usually found only near arroyos (drainages) where more moisture is available. Along the trail are juniper, piñon, rabbitbrush, yucca, saltbrush, mountain mahogany, and other plants that the people depended on for food, medicines, dyes, spices, and tools.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here, or simply scroll down for our next stop.

|

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

I thought that in addition to the movie, I would take a panoramic picture looking east in the general direction we would be going (and from which the return part of the circular trail would be coming). You can pick out Fred and Guy in the middle of the picture. Here is that panorama:

|

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here, or simply scroll down for our next stop.

At the top of that first ladder, we were actually on the "lower cliff", and as we headed off on the trail, we were actually walking along a section where the outbound and return trails are coterminous for a while (even though the diagram above separates them a bit so that stops along the return portion can be numbered without confusion). The trail then splits as you head towards the "upper cliff".

|

The petroglyphs here are only a few of many along this section of the trail; we will see many more at another stop on the return part of the trail. There are human-like figures, bird designs, four-pointed stars, and other symbols. The large figure on this rock appears to have cornhusks or feathers on top of its head. Petroglyphs are common throughout this area and much of the American Southwest. Meanings of some are still known to present-day Indians. Because they are carved into soft tuff, even touching these petroglyphs can cause permanent damage.

Eventually we reached the point where the outbound trail did diverge to head upwards; and here I took a couple of pictures:

Fred and Guy at the Trail Branch |

Interesting Rocks at the Trail Junction |

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here, or simply scroll down for our next stop.

This wasn't so much a "stop" on the trail as a description of the trail itself that we were following. It was certainly unusual, as Fred and I remembered from our visit years ago.

|

I took another picture from essentially the same place, and you can see part of the town of White Rock and, in the distance, the Jemez Mountains, the volcanic mountain range that is part of the Valle Caldera.

A little over a million years ago this volcano erupted several times covering the surrounding area in a thick layer of volcanic ash. Once compacted, the ash formed a rock known as tuff. The thick layers of tuff created a plateau that was easily cut by streams, leaving the flat mesas and steep-walled canyons you see. The volcanic tuff provided stone blocks for the construction of homes. The tuff was soft and small rooms (known as cavates) could be carved out using harder stone tools.

This is the same material, this "tuff" that formed much of the cliffs at Bandelier itself, and which allowed the Ancestral Puebloans to literally carve out their cliff dwellings.

|

Many sections of the trail we were following were worn 8 to 12 inches into solid rock, and in the picture of me taken halfway up, we passed through a waist-deep section. What looks like a trail intentionally cut into the rock is actually a trail worn into the rock!

|

Walking barefoot or in sandals along these routes from their mesa-top homes to the fields and springs in the canyons below wore even deeper impressions into the soft stone. Present-day visitors with hard-soled shoes cut the trails even deeper. Erosion adjacent to these early trails became a major problem as people avoided walking in the waist-deep trenches. A project in the late 1990s used fill material to repair the badly worn trail.

|

|

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here, or simply scroll down for our next stop.

|

Imagine living in this dry, open land. In the winter, an icy wind blowing from the mountains above could pelt you with bits of frozen snow forcing you to seek shelter in the protection of the cavates, such as in the small man-made caves carved into the soft tuff that are found at Stop #15. In spring, the lengthening rays of the sun would herald the beginning of the time to plant. In summer, you might closely watch the western mountains as towering clouds form and build hoping they bring the necessary rainfall to make your carefully tended crops grow. In autumn, the slopes of the Jemez Mountains would be colored with the gold of turning aspens, a sure sign the cold days of winter would soon return. You would want to make certain you had plenty of food in the storage rooms to supply your needs through the long winter.

Why did the people choose this and other similar mesa-top locations for their homes? The lack of soil here may be due to heavy livestock grazing in the 1800s. In the 1400s the mesa-tops may have been more likely places for farming than they are now. Some of the fields of corn, beans, and squash could also have been located in the canyons below to take advantage of runoff.

Today, there is no permanent source of water here. Prior to the development of the modern community of Los Alamos, there may have been a permanent stream to the north in Los Alamos Canyon. Mesa-top dwellers would have had to use pottery jars to carry drinking water from the stream, or store rainwater in structures like the ones you will see at marker 14. Mesa-top locations may have been chosen for defensive reasons, but there is no evidence of warfare or strife. Perhaps there were other reasons for which we have no evidence.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here, or simply scroll down for our next stop.

|

Here is a good view looking along the the edge of the mesa. and below is a panoramic view looking north from the upper cliff:

|

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here, or simply scroll down for our next stop.

|

From this vantage you can see the remains of those buildings (picture at left) in the valley to the northeast. (There are no trails down to this area.) Pueblo pottery is still a very successful art form, both as a commercial industry and as the continuation of an important daily activity of Ancestral Pueblo life. Today the revival of the pottery tradition is seen in the common black-on-black polychrome and red pottery of San Ildefonso Pueblo.

The people who lived at Tsankawi were not isolated. Many other villages were located on nearby mesas and in canyon bottoms. People of various settlements probably traded tools, pottery, blankets, agricultural products, feathers, turquoise, and seashells and joined together for social and religious activities. They were all competing for the resources of the area, especially game and firewood.

An enterprising hunter who tried to find more deer and rabbits by travelling far from his village would soon be approaching another. A trip to the mountains might be more successful, but the meat would have to be brought back- a long carry in a time when horses were not available. We spent some time at this spot looking around, and here are a couple of other pictures that we took:

|

|

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here, or simply scroll down for our next stop.

As you can see on the trail diagram above, these five stops on the trail are all clustered together, and that's because they all have to do with the ruins that we found next on the trail. So let me deal with all of them together.

|

The large settlement had about 350 rooms. Like Tyuonyi in Frijoles Canyon, the structures here were one to two stories high. Unlike Tyuonyi, there has been minimal excavation in this village. After the Ancestral Pueblo people moved from here the elements took their toll on the stone masonry of the pueblo. With passing time, roofs caved in and winds covered the walls with dirt. Plants, such as four-wing saltbush and snakeweed, which prefer disturbed soil, followed further obscuring the pueblo. The layers of soil, roots, and rock actually protect the buried site. Actually, were it not for the identifying signage, one would hardly know a pueblo had been here.

The settlement was roughly rectangular in shape and enclosed a large central courtyard or plaza. Everyday living activities occurred in the plaza along with various dances and ceremonies. The architectural plan of room blocks surrounding a central plaza is still used in the villages of present-day Pueblo Indians. The rooms were constructed of tuff blocks, shaped using harder stones and then laid-up with mud mortar. Walls were then plastered inside and out. Roofs were made of wood and mud. Archaeological evidence indicates Tsankawi was probably built during the 1400s and inhabited until the late 1500s. Archaeologists refer to this time as the Rio Grande Classic Period. Local people left the many small villages throughout the area and moved together to build large pueblos such as Tsankawi.

|

|

We were standing near the central plaza of the village of Tsankawi. Here within the protective walls of the pueblo much of the daily work of the Ancestral Pueblo people would have occurred. Imagine this plaza filled with the sight and sounds of people working and playing. Along with hunting and farming, flint knapping was a man’s job. Using a tool made of deer antler, obsidian was flaked to form arrowheads and knives. Women cooked, maintained the living quarters and made pottery. Similar pottery is still being made in the San Ildefonso Pueblo today.

|

The people of Tsankawi were not isolated from the rest of the world. You probably arrived here in a motorized vehicle. Ancestral Pueblo people traveled by foot. Trade brought items such as live parrots, copper bells, and seashells from distant places like the coastal US. Turquoise, salt and cotton were traded within New Mexico. There were no wheeled vehicles or beasts of burden to assist in the movement of these items. Imagine the life of a trader walking miles and miles in your woven yucca sandals, entering little-known villages, carrying the currency of your trade upon your back. Stand here and envision walking to the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the long mountain range you see about 20 miles to the east (to your right). Traders undoubtedly walked distances much greater than that.

|

Today there is no permanent source of water at Tsankawi. Prior to the development of the modern community of Los Alamos, there may have been a permanent stream in the canyon to the north. Having a reliable source of water nearby would have been very important to the people living at Tsankawi. Although there is no evidence of warfare or strife here, mesa-top locations may have been chosen for defensive purposes and for enhanced communications with nearby villages.

|

In today’s real estate market there is a saying that the three most important things when buying a home are “location, location and location”. Although like us the Ancestral Pueblo people may have enjoyed the panoramic views from this mesatop setting, this site was probably chosen for more than just its aesthetics. Outcroppings of volcanic tuff provided materials for home construction. The soft tuff also allowed the creation of small carved rooms (cavates). Small fields in the valley below yielded crops of beans, corn, and squash.

Why did the village have so many rooms? Being farmers, the people would have needed plenty of space for storage of dried corn, beans, and squash. The food they stored had to provide for their needs not only for the present year, but also for times when there were crop failures. Other rooms would have been used for cooking and sleeping, and special chambers (know by the Hopi term kiva) were used for gatherings for religious and other purposes.

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

Beyond the ruins, the trail continued a short distance across the upper cliff to arrive at the top of a 12-foot ladder that led back down to the lower cliff. After we left the ruins, I made a short movie as we traversed the upper cliff to get to the ladder, and you can use the player at right to watch that film.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here, or simply scroll down for our next stop.

After our trek across the mesa, we arrived (along with some other folks who'd been on the trail) at the top of the ladder leading down to the lower cliff. We had to wait for the other folks to go down the ladder.

|

|

I did get one picture of Guy descending the ladder, although it's not very flattering since I'd already descended the ladder and was looking up at him. You can imagine what part of his anatomy featured most prominently in the picture. It appeared that the trail went in both directions from the base of the ladder. However, the guide said that the trail to unsafe cliffs and a dead-end, and so hikers should take the trail to the right which would go along the lower cliff shelf for a ways and then eventually descend down off the mesa entirely and back to the parking area.

|

|

Most of the caves carved into the soft tuff cliff had small masonry buildings, known as talus pueblos (talus is the loose stone at the base of a cliff), constructed in front of them. These buildings have long since collapsed. Often the only remaining evidence of them are the socket holes where roof timbers were anchored. (This last picture was taken a short distance further along the trail, and you can see that the setting sun has finally gotten below the clouds; this will help us when we look for petroglyphs.)

Try to imagine what it might have been like to be cooped up inside these small rooms during long, cold, snowy winter nights with a smoky fire for light and heat- summer must have been welcome! All the nearby mesas have cave rooms on the south-facing side- a real advantage in winter. The afternoon sun would warm the cliffs, melt the snow, and allow the people to spend at least a few hours outside on sunny days. By contrast, the north-facing slopes often retain their snow cover throughout the winter.

Here are a couple more views of some of the cliffside caves:

|

|

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here, or simply scroll down for our next stop.

Movement from the area where the cliffside caves were up to the mesatop pueblo would have been constant. Stairways or hand and toehold trails were cut into the stone in places. They provided safer and easier access from the cliffs to the mesa. Imagine carrying a small child or a vessel filled with water up and down the steep cliff. This soft, fragile rock is very dangerous to travel on today and is easily damaged by our footwear. These stairways have suffered unnecessary damage from use by present-day visitors.

Now that the sun has come out for a while before it sets, the pictures of our travel through this area and more of the worn trails we saw earlier are much prettier as the rocks are lit up by the setting sun. We took quite a few pictures, and I've put the best of them into a slideshow for you to look at. That slideshow is below, left. As always, go from one picture to another by clicking on the little arrows in the lower corners of each one.

|

|

|

(Mouseover Image Above for Video Controls) |

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here, or simply scroll down for our next stop.

At this point in the trail we came to a large collection of petroglyphs, and the stroke of luck was that the setting sun was directly illuminating them.

|

One panel we saw contained carvings of arrows that were not of Ancestral Pueblo origin. For a time Spanish sheepherders kept their stock in small pens built under rock outcroppings here at Tsankawi. These historic additions probably date from Spanish-Colonial times- the late 1800s. Here are some other good pictures of these petroglyphs:

|

Standing here surrounded by the caves, canyons and mesas, imagine how different the area was when inhabited. Most caves would have had one or more small, square, smoothly plastered rooms in front. Most of the nearby trees would have been cut for roof beams, tools, or firewood. The canyon bottoms would have been covered with agricultural fields. Around you would be all kinds of activities- women cooking, sewing, grinding corn; men tending the farms or making tools; children playing. The sounds of people singing and children, dogs, and turkeys chasing each other would have filled the air, along with smoke from household fires and the smells of cooking, meat drying and many people living in close quarters. It would have been a lively busy scene, far different from today's atmosphere of quiet and solitude. Fred is very interested in petroglyphs and pictographs; we have taken numerous pictures of them all over the American Southwest, and here we spent a fair amount of time looking up at them before continuing on along the trail.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here, or simply scroll down for our next stop.

Below us, when the Pajarito Plateau was occupied by the Ancestral Puebloans, the canyon bottoms would have been covered with agricultural fields.

|

|

Men and women would have planted seeds using a digging stick made from Apache Plume or Mountain Mahogany. First the ground would have been softened using a hoe, a smooth flat stone attached to a long, straight limb. Corn was planted deep into the soil where residual moisture increased the chances it would sprout. Corn, bean, and squash seeds were intermingled; growing seedlings could use each other for support and shade. Even so, a good harvest was completely dependent upon sufficient moisture from summer rainfall. Most occurs during afternoon thunderstorms in July and August.

The trail guide cautioned us to be careful not to be caught in one of these fast moving storms in the open landscape at Tsankawi. No chance of that this afternoon, but plenty of opportunity to take a beautiful panorama of the area:

|

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here, or simply scroll down for our next stop.

The remainder of the trail was a navigation of more of the worn trail through the rock, and then a walk along the lower ledge and back to the first ladder.

|

After we hand gotten to the bottom of the worn trails, we found ourselves on a rock ledge that led entirely around and back to the bare rock area that we'd found at the top of the first ladder. Just before we got there, we passed the trail that we had taken up originally.

|

On a summer day, colorful lizards sun themselves on the warm rocks. Looking closely, the guidebook said, we might spot the bright blue belly of a male fence lizard (too late in the season for them now). A shame, for when they are approached too closely, they try to intimidate you by doing what appear to be pushups. Too late for the lizards and too early for the ravens that frequent the mesas in the winter.

Return to the Tsankawi Trail map by clicking here, or simply scroll down for our next stop.

Let me just complete the trail by including here the final guidebook entry:

| For countless generations people lived here raising families and surviving on the land. The land provided for their needs and the people were thankful. A time came when circumstances (drought, depletion of resources, and other factors unknown) forced the people to move on. With them they took traditions and beliefs built in a time when people lived in balance with the spirit of the land, giving back for all that was taken. Today the Pueblo people continue those traditions and beliefs. In a time when children eat sugared cereal, play video games, and watch endless hours of television the Pueblo elders strive to keep the old ways relevant to a new generation. Traditional pottery making, feast day dances, and singing are time-honored activities that can often be witnessed at San Ildefonso and other nearby pueblos. Today being a Pueblo resident often means finding a balance, keeping one foot in today’s world and one foot in the world of Pueblo tradition. |

Dinner in Los Alamos

It was getting pretty late when we got back into the car, so we drove back into Los Alamos for dinner. Fred had scoped out a few restaurants online before we left on the trip, and we settled on a casual place called The Blue Window right on Central Avenue just down from the Fuller Museum where we'd begun our day. The meal was quite good, even though we had to wait the better part of a half hour to get seated.

After dinner, we drove back to Chimayo for our last night at the Paradise Pond B&B.

|

October 26, 2018: Paradise Pond B&B and Our Trip Home |

|

October 24, 2018: Historic Chimayo and Ojo Caliente |

|

Return to the Index for Our Trip to New Mexico |