|

Return to November 22, 2014: A Museum Tour of Lima |

You have arrived at this page from the page for November 22, 2014- our last day in Lima. This page will take you through the amazing Larco Museum of Pre-Columbian Art. At the top and bottom of this page there will be a link to return you to the page for November 22.

Introduction to the Larco Museum of Pre-Columbian Art

|

During that same year, Larco Hoyle received some advice from his uncle, Victor Larco Herrera, a founder of the first museum in Lima. He urged Larco Hoyle to form a new museum in Lima, one that could guard all the archaeological relics that were continually being extracted by clandestine excavators.

Larco Hoyle agreed with his uncle and proceeded to create a museum that would carry on his father's legacy. Larco Hoyle purchased two large collections- 14,000 pieces altogether. He also purchased several small collections from persons and towns elsewhere in Peru. Within a year, the collection had grown significantly and display cases were installed in a small house on the Chiclín estate. On July 28, 1926, Independence Day, the museum opened its doors to the public.

The Larco Museum now lends some of its collection to its daughter museum, the Museo de Arte Precolombino (Pre-Columbian Art Museum), located in Cusco, Peru.

Entering the museum proper, we found ourselves in an open courtyard, with entrances to the facilities and the main galleries. This completely enclosed courtyard was really neat, and I have stitched a series of pictures together to give you almost a 360° view of it:

|

To work our way through the museum's galleries, we generally followed what seemed to be a general timeline- from the earliest, crudest artifacts to the later, exquisitely-created decorative objects. Due to the way the galleries were laid out, though, we sometimes had breaks in the timeline as we went from one wall to another or one room to another. So while the items we saw and the pictures we took of them follow the general timeline, that timeline isn't strictly linear.

The other thing to mention is that I tried to take pictures of as many of the description plaques as I could, because there was not nearly time enough to read everything, and I wanted to have a chance to do it later, at my leisure. Where these descriptions are short, I'll just transcribe them into this narrative. Where they are more extensive, I will include the picture of the plaque itself, enlarging it enough so you can read it for yourself- usually in a scrollable window.

With those things in mind, let's start our tour.

At the beginning of the exhibit, we found some information on Rafael Larco Hoyle and some general information on Peruvian Archaeology.

|

Next, here is some information on the geography of Peru:

The last part of the introductory sequence involved the process of stratigraphy- cataloguing artifacts in the context of the rock and soil strata in which they are found, and the other artifacts found in the same strata:

|

Generally, the exhibits followed a timeline, through seven "epochs" that Larco defined; these were based on changes in the formation or the subject matter of the art, and the epochs varied somewhat according to where in Peru the peoples were. The seven general epochs that Larco laid out were:

|

Pre-Ceramic Epoch (8000 BC - 2000 BC) Early Ceramic Epoch (2000 BC - 1250 BC) Formative Epoch (1250 BC - 1 AD) Apogee Epoch (1 AD - 800 AD) Fusion Epoch (800 AD - 1300 AD) Imperial Epoch (1300 AD - 1532 AD) |

With these epochs in mind as a general guide, we began to work our way through the exhibits. These were divided generally into areas, such as ceramics, textiles and the decorative arts. We will work our way through area by area, keeping in mind that each separate area referenced the "epochs" that are listed above.

Ceramics and Pottery

Pre-Ceramic Epoch (8000 BC - 2000 BC)

Ten thousand years ago the hunter-gatherers who had begun to inhabit the coast learned to exploit the resources of Peru's seas. The fished and hunted using stone spearheads. The also made cotton nets for fishing. These people built the first coastal settlements, some of which are almost 5000 years old. Archaeological sites like Paijan, Huaca Prieta and Caral date from this period.

Early Ceramic Epoch (2000 BC - 1250 BC)

|

These societies began to produce open-fired pottery. The first designs of vessels resembled the fruits and animals of the surrounding environment.

From the beginning of the ceramic phase to the perfecting of this technology during the Formative Epoch, around 800 years elapsed, and archaeological sites like Queneto, Curayacu and Kotosh date from this period.

Formative Epoch (1250 BC - 1 AD)

As implied by the name that Larco chose for this epoch, this was a time during which styles were formulated and accepted. It was a time when artisans reflected their natural world, concentrating on those aspects of it which they believed were involved with the direction of the human race.

|

|

They produced sculptured vessels shaped like animals, fruits, human heads and houses. The most characteristic element is the stirrup handle.

Near the displays we had seen thus far, there were two interesting informational plaques that talked about aspects of the ancient Peruvian culture that impacted their art, and you might want to read them, so I have put each one into a popup window for you. To read either or both of these interesting displays, just click on its title below:

|

|

Continuing with the items on exhibit, you will find three kinds of entries. One will be something you can read, and I'll show you those as I did the two above. Sometimes, there will be a single picture with a description of the item (no clicking involved). And third there may be a series of thumbnails (usually the items in a single exhibit) with the description next to them. In this case, click on any of the thumbnail images to see a full-size picture of the item(s):

|

They also represented the owl, a nocturnal bird, and the condor in stylized designs which featured the fangs of felines and serpents. Birds represented the power of the skies, while the feline and the serpent represented the power of the earth and the subterranean world, respectively.

CUPISNIQUE ANTHROPOMORPHIC FELINE The religions of the Formative Epoch created gods in human form but with the supernatural powers of the feline. On Earth, the supreme leaders assumed the power of the feline. The great religious, political and economic power they accumulated enabled the development of more efficient production methods. The faces of these figures are a combination of human features and those of the feline, such as teeth, whiskers an dalmond-shaped eyes. |

PACOPAMPA STELE Representing a female anthropomorphic deity with feline, bird and serpent features. Between the figure's legs one can distinguish the vaginadentata, a feature which appears in several representations of the goddesses of ancient religions. |

SALINAR This culture was discovered by Rafael Larco Hoyle in 1941 in the Chicama valley in the department of La Libertad. The ceramics were fired in kilns in which the oxygen oxidized the clay giving them a brick-red color. They were then painted with white lines. This "white on red" decorative technique endured until the end of the Formative Epoch. Among the sculptural pieces we see again the feline, the serpent and the owl. the cult of the dead was very important, as can be seen in this sculptural scene depicting a body prior to burial. |

VICUS The Vicus culture deeloped in the department of Piura in the far north of Peru. This region functioned as a cultural frontier between the areas now occupied by Ecuador and Peru, and the artistic characteristics of both regions can be seen in Vicus art. Ceramics were decorated using both the negative and positive painting techniques. The individuals represented have so-called "coffee bean eyes". This double chambered sculptural vessel decorated with the negative painting technique represents a nude male with a painted body. He is wearing a metal crown with flaps like the one that can be seen in the Gold Room of the Larco Museum. He is also wearing very large ear plugs- an indication of high rank- and a necklace made from beads shaped like human faces. |

|

PARACAS CAVERNS

FORMATIVE EPOCH (1250 BC - 1 AD)

The Paracas culture inhabited the valleys of Chincha, Pisco and Ica. They were known for their elaborate burials, clearly illustrating the great importance of the cult of the dead. The piece at right is covered with the incised decoration characteristic of the Formative Epoch.

The paint was applied in thick layers after firing. The main colors employed are greenish-brown, red, black, pastel, blue, white and yellow.

The way in which the feline is represented is reminiscent of the art of the Cupisnique culture; it appears anthropomorphized and highly-stylized.

VIRU This culture was discovered by Rafael Larco Hoyle in 1933 in the Viru Valley, in the department of La Libertad. In their ceramics the negative decoration technique dominated. The red designs were covered with very fine clay, while the parts that were left uncovered darkened during firing. The covered parts did not darken, and this created the negative painting effect. Here we see a serpent with two feline heads and a bird perched on it, the feline with the face of an owl on its breast, and a four-legged bird. All of these hybrid creatures are a combination of the bird, the feline and the serpent. These hybrid creatures represent the union of the powers of the sky, earth and underworld. This union reflects the growing power of the rulers. You can click on the thumbnails below to see a couple of these items up close:

|

|

This is probably a good time to talk about pottery technology, and there just happened to be an exhibit on that very subject.

|

The primary material for the making of Moche ceramics consisted of red and cream-colored clays, as well as kaolin or white clay.

The pigments used to give color to the slip and paints were mostly mineral-based, particularly ferrous oxides.

Bone tools were used to decorate the ceramic after modeling. Molds and stamps were also used to apply some designs.

Some ceramic objects were flawed, but they were still conserved by ancient Peruvians.

The Apogee Epoch (1 AD - 800 AD)

MOCHE SCULPTURAL CERAMICS Moche potters achieved a high level of quality and sophistication in their sculpture. They modeled very expressive scenes which represented natural movements. Animal mythology combines the feline, the bird and the serpent. In the left-hand picture, the turquoise eye belongs to the feline and the bird, the beak of which points backwards. The tail and fur of the feline are stretched out behind the creature like serpents. In the right-hand picture, a high-ranking male is seated at the top of a stepped pyramid with an access ramp. He is wearing a highly-decorated tunic and a headress like the one worn by the god.

|

Moche rulers were the earthly personification of the gods. Their attire and adornments evoked the bird, the feline and the serpent. You can read more in the scrollable window below:

MOCHE FINE LINE POTTERY Like all agricultural societies, ancient Peruvians were fundamentally concerned with the acquiring of knowledge regarding the cycles of nature- such as those marked by the returning of the seasons. They believed that in the sam eway we humans are born, live, die and pass on to th esubterranean world, from where all life is reborn. The world is animated by opposing forces which at the same time are also complementary. At the center of the Andean world view is the concept of duality- similar to the concepts of yin and yang in eastern philosophy. The forces which animate the world are in constant movement, and this is represented by the spiral symbol. The Andean world was divided into three planes- the world above, the earthly world and the underworld. These are represented by the stepped symbol, and a scroll in the upper part symbolizes the dynamic between these worlds. Using the artistic technique known as "fine line", the Moche embodied these concepts in their pottery. |

The works of art that we see in museums were not usually objects intended for daily use. Although some of their apparently utilitarian forms may suggest such usages, their real function was to serve as spiritual rather than earthly objects. You can read more about these concepts in the scrollable window below:

|

The piece at left is an anthropomorphic owl dressed as a warrior and standing under an arch formed by a serpent with two feline heads. This is one of the principal got left ds of Moche culture, and it is associated with the night, the occult and death.

In contrast with contemporary art, which is freely produced by individual artists, in the past artistic production was controlled by the elite. Under the supervision of priests and great lords, Moche pottery makers achieved a high degree of artistic development. They produced naturalistic sculptures and drew scenes on the surfaces of their pottery using the so-called "fine line" technique. You can read more in the scollable window below:

|

The item at right is a Moche cup featuring a mythological narrative. The protagonist is one of the culture's principal deities, named Ai Apaec by Rafael Larco. He has a feline's fangs, a headdress representing the head of a feline and incorporating bird feathers and a belt tipped with serpent's heads. The events depicted are his arrival in the world of the dead and his struggles against other gods and demons.

|

MOCHE PHASES

|

The evolution of the shape of the handle and spout, the rim of the spout, the relationship between the main body of the vessel and the stirrup spout, the type of paint used and the details of the sculpture are some of the variables which contribute to the defining of the sequence of five phases proposed by Rafael larco. This sequence is supported by the stratigraphic position of the tombs in which they were found.

The Moche culture flourished and then quickly declined. This decline of the Moche state was the result of the weakening of the political-religious power of the rulers. Subsequently, on the north coast of Peru, the states of Lambayeque and Chimu emerged.

Most of the pictures so far have been mine (in my effort to document everything, but Fred has also been photographing items that I missed. Here are clickable thumbnails for some of his pictures:

|

Out in the center of the room we were in was one of the largest figures in the exhibit- a standing figure. I did not notice an identifying placard nearby, but it was an interesting figure nevertheless.

|

Moche was one of the few ancient civilizations which produced true portraits. These works accurately represent anatomical features in great detail. There is particular emphasis on the representation of the details of headdresses, hairstyles, body adornment and face painting.

The individuals portrayed were members of the ruling elite, priests, warriors and even distinguished artisans. The faces of gods were also depicted. To date, no portraits of women have been found. Below are clickable thumbnails for more of these portrait vessels:

|

Larco categorized his finds, as we have seen, not only by the epoch it was from, but also by the culture that produced it. The Moche culture, one of the northern cultures, was extensively represented.

|

|

You can learn more about the cultures of southern Peru (the most familiar of which was the Nazca culture, due to the widespread interest in the "Nazca lines", those huge geometric and linear shapes etched into the landscape that some say can only be viewed in their entirety or even be understood to be particular shapes if viewed from the air, something the Nazca people would not have been aware of) by reading the information provided here in the exhibit about them. You can use the scrollable window at right to do so.

As I said above, Fred had been photographing other pieces that I missed, and there are clickable thumbnails below for some of his pictures so far:

|

|

Nazca A or Monumental pottery is naturalistic and colorful. The paint covers the entire surface of the vessels. the predominant forms are the small double spout and bridge designs. Sculpture was less developed. In their pottery, Nazca artists represented the fauna dnd flora of their environment. They depicted the detailed features of animals and fruits with great skill and delicacy.

They depicted fishermen and famers as well as hunting scenes and combat between warriors. The "decapitator deities" were also represnted. Another frequently occurring motif is the trophy head. The anthropomorphic feline deity appears on a large number of drinking vessels and it is depicted as a combination of the features of the feline, bird and serpent.

|

NAZCA DRUM

APOGEE EPOCH (1 AD - 800 AD)

This piece is a Nazca drum representing a mythical ancestor who is wearing a headdress with the head of the feline god. In the middle of the ancestor's chest there is a mythical feline. Two serpents with feline faces emerge from the mouth to envelop the body of the main figure.

Among Nazca ceramics, it is the drums which bear the richest iconography. They are loaded with religious symbolism. In Nazca culture, drums and panpipes were used in the ritual processions and dances associated with agricultural fertility and the cult of the dead. You can learn more by reading the wall plaque in the scrollable window below:

|

NAZCA B

APOGEE EPOCH (1 AD - 800 AD)

In Nazca B or Proliferative Nazca, the decorative motifs of ceramics multiplied, reflecting a "harror vacui" (fear of empty space). They feature complex representations of humans, animals and supernatural beings. Natural representations were rare. The feline continued to be worshipped as a god and was represented in a stylized form- a flying feline with a large nose ornament. Some of the rays are tipped with the heads of serpents. Once again we see the combination of feline, bird and serpent features. Another frequently seen motif is the trophy head. These are so stylized that they appear as small triangles with three markings.

|

|

Larco talked much about the cultures of the north and south, but thought the cultures of the central coast (where today's Lima is) were also important. The central coast of the country was a meeting place for the cultural traditions of the north and south. You can read more about this cultural amalgam below:

|

Lima-Nieveria pottery, produced on the central coast, displays features from the cultural traditions of both northern and southern Peru. It incorporates sculptural scenes from the northern tradition, while its southern influence is characterized by the double spout and bridge design and polychrome decoration. The dominant color is bright orange.

You can see a close-up of the left-hand item in the picture at left here. In an adjacent display there was an interesting spotted feline.

|

SANTA

APOGEE EPOCH (1 AD - 800 AD)

Also known as Recuay, this culture developed in the highlands and coast of north-central Peru.

Its pottery is sculptural and scenographic. In the painted designs a stylized feline dominates. Appendages emerge from the head and face of what is known as the "rampant feline" or "lunar animal". This creature is frequently seen in the art of the Moche culture, which was a contemporary and neighbor of the Santa on the northern coast of Peru.

|

The Tiahuanaco culture developed in the highlands around Lake Titicaca (between present-day Peru and Bolivia). This culture is known for its monumental sculpture and stone architecture.

Its red ceramics differ from the cups known as keros. They are mostly decorated with geometric motifs and stylized feline and condor heads.

|

CAJAMARCA

APOGEE EPOCH (1 AD - 800 AD)

Cajamarca ceramics, from th ehighlands of northern Peru, are characterized by their geometric motifs and stylized zoomorphic designs. The cursive painting differs from the other pictorial styles of ancient Peru. The decoration was applied both on the interior and exterior of the piece.

The principal forms of this pottery were tripod vessels, cups with bases, and plates. The predominant colors were cream and orange.

The Fusion Epoch (800 AD - 1300 AD) and the Imperial Epoch (1300 AD - 1532 AD)

The Chimu Empire of the north coast and the great Inca Empire which expanded from the southern highlands represent a synthesis of the two major cultural traditions of ancient Peru. Read more below:

The Huari culture was important, and had a presence in northern, central and southern Peru.

|

CENTRAL HUARI

FUSION EPOCH (800 AD - 1300 AD)

The Humaya style originated on the central coast and displays the influence of the Huari style and the Lima-Nieveria style. It inherited the orange color employed in Lima culture ceramics and the pictorial motifs of the Huari culture.

The pottery of the Fusion Epoch from the central coast displays elements of Huari art but it lacks the sheen and fineness of that culture's ceramics. Initially, colorful pottery dominated, but gradually the tendency disappeared and the quality of the workmanship declined.

Elements of the ceramic art of the Chancay culture can also be seen in these styles: the human face is represented as a triangular form and the surface of the pottery was left unpolished.

|

The influence of Huari art from southern Peru introduced new traits into the pottery of the north, such as the presence of more colors and double spout and bridge vessels.

Huari art is characterized by geometric motifs outlined in black. It is common to find representations of humans and religious motifs. The feline deity is represented wearing a belt in the form of a two-headed serpent, serpent ear plugs, and wings.

There are clickable thumbnails below for more examples of Huari pottery from this period:

|

Here are clickable thumbnails for more of the items that Fred has been photographing independent of my own movement through the exhibits:

|

|

PACHACAMAC

FUSION EPOCH (8 AD00 - 1300 AD)

Pachacamac, located in the Lurin Valley, was the most important ceremonial center on the central coast. Very high quality pottery from the Fusion Epoch has been found at this site. This pottery is predominantly red, black and cream in color and was clearly influenced by Huari culture.

The most characteristic representation is that of a zoomorphic figure known as the "Pachacamac gryphon", a fantastic animal which is a cross between an eagle and a feline, with a three-pointed crest, often represented holding a knife. You can see another piece of pottery decorated with this animal here.

LAMBAYEQUE FUSION EPOCH (800 AD - 1300 AD) In Lambayeque pottery there is a continuation of the sculptural tradition of the north. The double spout and bridge handle forms of the vessels come from the southern pottery tradition. These ceramics feature a figure with wing-shaped eyes, pointed ears with large ear plugs and a half-moon headdress. this individual would have been conceived as a representation of the mythical heroic founder of the ruling dynasty, known as Naylamp, who was deified. He appears accompanied by other lesser figures.

The great lords of the kingdom of Lambayeque were buried wearing metal masts in the likeness of this deity. There are clickable thumbnails at left for two more examples of this art. Fred took a picture of the showcase of Lambayeque pottery, and I zeroed in on the feline in the lower left of the display.

|

|

INCA

IMPERIAL EPOCH (1300 AD - 1532 AD)

One of the characteristic forms of Inca pottery is the urpu, or aryballos. This vessel has a spherical or globular body and side handles. The spouts of these vessels end in an elongated and flattened lip. Another typical element is the application of a small feline head on the front of the vessel (see picture at right).

In Inca art, the majority of the ceramics produced were pacchas- ceremonial vessels associated with the worship of water. A lo tof color was employed in the decoration, in keeping with the style of the southern tradition. The vessel at right was in a case with two other examples, and you can see the whole showcase here.

Again, I want to include some of the additional pictures Fred has been taking, and there are four clickable thumbnails below for some of them:

|

|

In Chimu ceramics, we can detect a revival of the northern tradition after a 300-year period of southern artistic influence. Stirrup-spout vessels once again became the dominant form. In the area between the spout and the handle of these pieces, there is a small representation of a monkey. In common with the traditions of Moche art, sculptural ceramics once again assumed a major role.

The Chimu elite chose black ceramics over markedly southern forms such as polychrome designs and the use of the double-spout bridge-handled vessel. Chimu ceramics wee made using molds and pieces were mass produced.

While two thousand years earlier the feline had been represented as a powerful figure, vanquishing the deer, in Chimu art a human was represented carrying a deer on his shoulders, thereby transmitting a message related to the humanizing of power.

|

CHIMU-INCA

IMPERIAL EPOCH (1300 AD - 1532 AD)

At the time of the Spaniards arrivval on Peru's northern coast this type of pottery ws produced by the Chimu under Inca rule. You can see the items in this particular display here.

In this pottery we can see features of the cultural traditions of the north and south. The sculptural element of the north is maintained, togethe with the design in the space between the spout and the handle, in keeping with the tradition of Chimu ceramics. The typically southern use of polychrome designs and the flattened spouts of Inca ceramics are retained.

The double chamber and double spout linked by a bridge are characteristics of Chimu-Inca art. The feline continued to be frequently represented as the principal deity. The rightmost piece in the display you saw above was particularly interesting, with the bird figure atop the vessel. You can have a closer look at it here.

|

Chancay pottery, with its unpolished surface, was usually white with geometric designs in black or brown.

The sculptures of men and women in a standing position with raised arms are known as "cuchimilcos". These large figures were dressed with textiles and were usually placed in pairs in tombs.

This culture achieved a very high level of quality in its production of textiles. Gauzes and tapestries were used to wrap the dead laid to rest in Chancay tombs. Potters reproduced ritual scenes which accompanied the dead into the afterlife.

|

CHINCHA

IMPERIAL EPOCH (1300 AD - 1532 AD)

The Chincha chiefdom emerged in the southern valleys. The Chincha were mariners and traders and skilled weavers. Their most characteristic pottery form was the bowl. With their beautiful combinations of geometric motifs, these bowls give the impression of being bordered by woven sashes.

CHINCHA-INCA

IMPERIAL EPOCH (1300 AD - 1532 AD)

The Incas conquered the Chincha chiefdom, and after this conquest the styles, colors and designs of these cultures were combined. The aryballo form denotes the presence of the Incas. The handle joined to the neck of the vessel is an inheritance from Chincha ceramics. There were three examples on display; click on the thumbnails below to have a look at them:

|

|

Imperial Inca ceramics are characterized by the "urpu" or "aryballo" form. A small zoomorphic head, usually that of a feline, was applied to the upper front part of the main body of the vessel.

Another characteristic feature is the addition of ribbon-like handles on cups, pitchers and bowls.

The use of several colors, as well as geometric decoration, is evidently an example of the southern cultural tradition.

|

INCA ARYBALLOS

IMPERIAL EPOCH (1300 AD - 1532 AD)

One of the typical forms of the pottery of the Inca Imperial phase was the "urpu", also known as an "aryballo" because of its similarity to Greek vessels. Huge aryballos wee produced. They were used to make, store and transport "chicha", the ritual drink made from fermented corn, and other edible products which were shared during the festival of redistribution organized by the Inca. The base of the aryballo ended in a point so that it could be inserted in the ground.

The other typical Inca pottery form was the "kero", or ceremonial cup. This form was inherited from the art of the Tiahuanaco culture. The keros were usually made from carved wood and decorated with incisions. These ceremonial drinking vessels continued to be made during the colonial period and they were decoratedd with colorful carved and painted scenes. Keros are still made by Andean communities.

The Conquest (1532 AD -)

The dramatic encounter between the world of Europe and the indigenous societies of the Americas that started in the 16th century placed in opposition two distinct ways of understanding and organizing the world. Read more in the scrollable window below:

|

With the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores, elements from European culture were introduced into Andean Art.

At first the ceramics produced echoed the Inca designs of double‑chamber, double‑spout and bridge vessels. European influence in these pieces can be seen in the yellow, brown or green glaze which was produced with a lead varnish and higher temperature kilns. Ceramics that imitated the metal pans of Europe were also produced.

One of the subjects represented in pre-Columbian art is the feline attacking a deer or a man carrying a subdued deer. After the Spanish conquest, a variation on this theme appeared: a powerful man carrying a feline (see the object at left). For the first time in Andean art, the feline god appears overpowered and defeated as if it were a deer, thereby reflecting the effect upon indigenous religious beliefs of the process known as the "Extirpation of Idolatries".

Let me conclude this section on ceramics with clickable thumbnails for the last of the pictures Fred took of items that I missed:

|

The area of the museum devoted to ceramics was certainly interesting but you are probably ready for something different.

Textiles

TEXTILE TECHNOLOGY

In ancient Peru, the principal materials used for spinning weaving were cotton and alpaca and llama wool. They were employed in a number of natural colors, from white to brown, and they were also dyed using mineral, vegetable or animal pigments.

|

Backstrap or fixed horizontal looms were used. With the help of a shuttle, the threads were passed through the warp to form the weft. Using a batten, the weaver pressed down on the thread, tightening it firmly. the combs helped the weaver to organize the threads during the weaving process. Fine needles were used to join the panels and embroider designs on the cloth. In many parts of present-day Peru, particularly on the northern coast and in the highlands, women continue to use these ancestral weaving techniques.

Baskets which contained materials and tools that would have been used by the spiners and weavers of ancient Peru have been found in pre-Colombian tombs.

Larco organized and categorized the textiles by culture and by epoch. Here are some of the examples that were on display:

|

This textile has rhombuses which frame a figure seen in profile and holding batons.

The technique was a simple plain weave decorated with the brocade or supplementary weft.

As far as the material, for the plain cloth white cotton thread was used, and for the decoration camelid fibers dyed in different colors were employed.

Fred got a closer view of this textile, and you can see that view here.

|

CHIMU

IMPERIAL EPOCH (1300 AD - 1532 AD)

This textile composed of six elements of equal size, each of which frames an anthropomorphic figure wearing a half-moon shaped headdress.

Fred also got a closer view of this textile, and you can see that view here.

|

This is a small, sleveless shirt (or "uncu") representing a tree with branches that end in leaves and zoomorphic heads. Two condors are perched on the upper branches. In the center of each tree a figure can be seen.

The technique employed is called "kelim" or slit tapestry. As for the material, a warp cotton thread was used, while in the weft both cotton fiber and camelid wool thread were used.

I took a closer picture of this textile to show more of the detail, and you can see that view here. Fred also got a good picture of it, an you can see his picture here.

|

PARACAS

FORMATIVE EPOCH (1250 BC - 1 AD)

This textile has a representation of supernatural figures carrying batons and trophy heads.

The technique is an embroidered fine plain weave and the material is a cemelid fiber thread.

Fred's closeup is a bit fuzzy, but you can see it here.

|

This textile is "mantle" decorated with geometric birds facing in different directions. The technique involved simple plain cloth with discontinued warp and weft. The decorative bands were achieved using the lacework tapestry weave technique. (You can see the bands if you look at the full-size textile. The material was a camelid fiber thread. I got an extreme closeup of the fabric, and you can see it here.

A mantle was part of the cult of the dead. Paracas mantles were used to srap funerary bundles and they contained important religious information which accompanied the dead into the afterlife. There was more information on this aspect of the culture posted near these textiles; you can read it in the scrollable window below:

There was also another mantle was hanging nearby.

|

NAZCA-HUARI

FUSION EPOCH (800 AD - 1300 AD)

This textile is decorated with stepped motifs and concentric, interlaced rhombuses.

The technique is a patchwork decoration with patches made from tie-dyed simple plain cloth. The material is a camelid fiber thread.

Looking at this fabric, I am reminded of two things. One is a quilt, or quilt-like shirt that looks like it is made from leftover fabric scraps. The other thing is a bit more odd- I am reminded of the old computer game Tetris.

|

This is a sleeveless shirt, or "uncu", decorated with a circle, squares and rectangles. The undecorated vertical band is set at the shoulder line. The central, horizontal opening is for the head.

The technique used here is a simple plain weave decorated with multicolored feathers sewn onto it. The material was plain cloth with a cotton thread.

|

WORLD RECORD THREADS

HUARI

FUSION EPOCH (800 AD - 1300 AD)

This is a fragment of a textile representing anthropomorphic heads with stepped appendages tipped with the heads of birds. This fragment is a second world record in terms of teh fineness of the thread.

The technique used here is that of a lacework tapestry weave; as for the material, cotton fiber was used for the warp, while the weft employed camelid wool.

The final textile wasn't really a textile at all, but rather a small, rectangular rug-like affair divided into four sections- two yellow and two black- in a checkerboard pattern. But it wasn't cotton or wool thread that was used; instead, small dyed feathers were affixed to a backing. You can see a closeup of this piece here.

QUIPUS

Quipus were the main system employed by the Incas to record information.

|

You can read more about this record system technique in the scrollable window below:

Syncretism

|

Above, left, and below you can see some of the artwork produced in Peru after the Conquest; it all looks very European, but on close inspection one finds Peruvian modifications.

|

|

|

Combat and Sacrifice

There were a number of items on display that pertained to the ceremonies involved with ritual combat, and four of them plus their descriptions are below:

|

WARRIORS MOCHE APOGEE EPOCH (1 AD - 800 AD) Warriors prepared for ritual combat. To show their high social position they dressed themselves with headdresses, feather ornaments, ear plugs, breastplates, necklaces, bracelets, decorated shirts, backflaps, rattles and face paint. They carried shields and weapons such as clubs, lances and spear-throwers.

************************************

CLUBS

Wooden clubs used in ritual combat. Their provenance is Huancaco, a Moche site in the Viru valley.

|

|

|

THE RITUAL COMBAT MOCHE [APOGEE EPOCH (1 AD - 800 AD)] A stone box inlaid with turquoise. The scene represents a ritual combat and the procession of defeated warriors.

END OF COMBAT / PROCESSION OF DEFEATED WARRIORS

Moche warriors faced each other with clubs and shields. Hand-to-hand combat took place in open areas. When a warrior removed another's helmet or grabbed his hair the combat was over. The defeated warrior was stripped and his weapons and clothes were wrapped in a bundle. The victors led the defeated warriors by ropes tied around their necks to the place of sacrifice.

|

|

While it isn't pleasant to contemplate, the practice of human sacrifice was common to many ancient cultures. Death, the shedding of blood and physical mutilation ritually transformed the victim. The life being offered to the gods gave the transformed individual sacred status (sacrum facere).

|

Scene illustrating the Sacrifice Ceremony and Presentation of the Cup containing the blood of the defeated warriors, which was offered to the major Moche gods.

The Sacrifice Ceremony was central to Moche religion. The offering of the blood of the vanquished to the principal gods was the climax of the ritual combat.

At several archaeological sites on Peru's northern coast the tombs of Moche lords and ladies have been excavated, and the adornments and other funerary objects discovered have enabled researchers to identify them as the individuals who participated in this ceremony. Below, left, is an enlarged view of the vessell above, enabling you to see the figures more clearly. At right, below, is an explanation of those figures. You cannot see the entire vessel, but you can relate the two together.

Below are some of the figures that are mentioned in the ritual done in ceramic from the Moche Apogee period:

|

|

The importance of sacrifices was quite high, and as a consequence not only ceramics were made depicting them, but metalworking skills (discussed a bit later) were also used to create items used in the ceremonies. Here are two such:

|

MOCHE DECAPITATOR GODS APOGEE EPOCH (1 AD - 800 AD) In Moche art the gods were represented fighting among themselves, or against other supernatural beings or humans. These battles ended with the decapitation of the defeated opponent. The gods are represented holding a half-moon shaped knife known as a "tumi".

MOCHE SACRIFICIAL CUP AND KNIFE

The warriors' throats were cut and their blood collected in ceremonial cups to be offered to the priests, the representatives of the gods. In the tombs of individuals who in life must have taken part in this ceremony, similar knives and cups have been found.

|

|

Sacrifices took different forms and were performed at different locations, and one display showed how this was reflected in the Moche ceramics:

|

Moche art illustrates other ways in which defeated warriors were sacrificed. Some ceremonies occurred on islands, with the warriors transported on rafts.

Another type of sacrifice took place in the mountains, and the warriors were thrown off a precipice.

In the art of ancient Peru, we can see how warriors fought wearing clothing and jewelry made from precious metals. This tells us that such combat had a ceremonial significance. Read more in the scrollable window below:

There were a number of displays of clothing and ornamentation that warriors would have worn or that participants in the sacrifice ceremonies would have used. Here are some of them:

|

CLUB HEADS (NORTHERN COAST) (1250 BC - 800 AD) Clubs were the most commonly used offensive weapons of ancient Peru and they were employed during warfare and in ceremonies. The handles of these clubs were made from wood, and the heads could be fashioned from wood, stone or metal. They were often shaped like discs,stars or rosettes, while others might be shaped like a cactus or a zoomorphic head.

MOCHE BACKFLAPS OR COCCYX PROTECTORS

As part of their clothing, Moche warriors wore an adornment on the lower part of their backs. In Moche illustrations of their customs we can see how this item covered the coccyx of the warriors, and that is why we call it a coccyx protector, or "backflap". It was shaped like a ceremonial knife and the blade was sharpened and appears to have been used, indicating that it may have been used for cutting. A rattle is incorporated into the uper part of this adornment. Here we find depictions of ulluchus, a fruit associated with sacrificial and fertility rituals. Coccyx protectors made from gilded copper, silver-plated copper and copper had gilded copper rattles.

|

|

|

CEREMONIAL TRUMPET AND WHISTLES (NORTHERN COAST) (1 AD - 1532 AD) The tropical mollusk Strombus was used in the Andes as a ceremonial trumpet, and this type of instrument was known as a pututo. The Strombus is a warm water seashell associated with the cycle of water. Water originates in the sea and then returns to the earth as rainfall and via rivers and canals it irrigates the land and causes plants to flourish. Pututos, which produce a strong, deep sound, were played by trumpeters in ceremonies associated with water. Strombus shells were also important offerings to the gods, who had to be thanked for the blessings they bestowed. That is why they are found in groups of offerings placed in important temples, beginning during the Formative Epoch. In ancient Peru, cerami trumpets were also made, and their designs recreated the shape of these seashells. Here we see a Moche trumpeter, Moche Strombus seashell pututo, Moche ceramic pututo, a miniature gilded copper Strombus and a Chimu whistle.

|

|

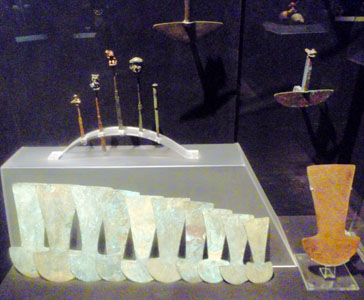

CEREMONIAL KNIVES OR TUMIS

Knives, or tumis, were represented in depictions of mythological scenes of combat as the weapons used by supernatural beings to decapitate their adversaries.

Ceremonial knives adopted a number of forms over time. Some were crowned by sculptural representations of animals, people or ritual activities. These pieces were made using the lost wax or casting technique.

|

|

|

|

WARRIOR CLOTHING MOCHE APOGEE EPOCH (1 AD - 800 AD) The luxurious clothing worn by warriors emphasizes the ceremonial nature of warfare. In Moche art, warrior chiefs wear conical-shaped helmets and carry clubs. In rituals some ceremonial knives also served as rattles and represented clubs. The miniature gold whistle represents a warrior with helmet and club. In this object, we can see the link between music and combat. Here we see silver helmets; copper clubs; gold-copper-silver alloy whistles; ceramics representing a warrior with a helmet, club and ceremonial attire.

|

Ceremonies

You can learn more about the importance of these vessels by reading the wall plaque entitled "Ceremonial Vessels". It is in the scrollable window below:

|

|

LIME CONTAINER MOCHE APOGEE EPOCH (1 AD - 800 AD) The container at left is the lime container; it was made from gilded copper and copper-silver alloy, using the techniques of raising, casting and soldering. The ceremonial chewing of coca leaves has been practiced in the Andes since ancient times. These recipients contained th elime with which the coca leaves were mixed. The lime was extracted with a stick which was then placed in the mouth of the person chewing the leaves, where it acted as a catalyst in the extraction of the alkaloid components of the coca leaf. The other container is, of course, the representation of the feline, and would be used for the most important purposes.

|

Music and dance were an important part of many ceremonies in ancient Peru. These artistic expressions created the proper conditions for the ritual experience. Learn more from the wall plaque that you can read in the scrollable window below:

|

(left) COPPER RATTLES (MOCHE) (1 AD - 800 AD) Musical instruments are represented in great detail in Moche art. They mostly appear in combat rituals and dances in the world of the dead. In these dance scenes, large rattles were used which would have produced deep, dull notes, thereby creating a sense of drama. rattles like these have been found in the tombs of individuals who participated in preparatory combat rituals. Originally, they would have had the reddish hue of copper, a color associated with ritual combat and sacrifices. Many instruments took animal forms.

(right) WARRIOR DANCE (MOCHE) APOGEE EPOCH (1 AD - 800 AD)

The Dance with a Rope was a ceremony in which warrior chiefs participated dressed in their finest clothing and personal adornments. Associated with ritual combat and sacrifices, it was common to many Peruvian cultures. In the dance as depicted on this vessel, the main protagonist wears the clothing of a warrior chief, with a conical helmet and coccyx protector. He also possesses the teeth of a feline, in a clear allusion to his supposedly supernatural character. This warrior appears at the center of the ceremony holding a rope, while two groups of warriors can be seen at his sides wearing their own ceremonial clothing. Some of the warriors wear shirts decorated with square plaques, while the shirts of others are adorned with metal decorations. Musicians playing a drum and flute and dancers are also part of the ritual.

|

|

Beginning at this point in our tour through the museum, metalwork took over from pottery as the main artistic form. In ancient Peru, the colors of gold and silver, associated as they were with the sun and the moon, coupled with their ethereal brightness and apparently eternal aspect, made these precious metals an expression of supernatural powers, and they were used not just for ornamentation but for the manufacture of vessels and other objects. You can learn more about the metails of ancient Peru by using the scrollable window below to read the rest of the wall plaque on the subject:

|

CEREMONIAL BOWL CHIMU IMPERIAL EPOCH (800 AD - 1300 AD) Made of silver and extensively engraved. Shown is a scene of collecting and offering of spondylus or mulla shells to a god or ancestor. Considered a food for the gods, these shells were essential items in the tombs of high ranking individuals in ancient Peru. Below are clickable thumbnails for the bottoms of two more ceremonial bowls:

|

Wandering through the gallery devoted to metalwork was interesting, and there were some beautiful items to be seen.

|

(left) CEREMONIAL CUPS CHIMU IMPERIAL EPOCH (800 AD - 1300 AD) Made of silver using a raising technique called "respousse", these cups were used by high ranking individuals in the presentation of ritual liquids or drinks.

(right) CEREMONIAL BOTTLES

These bottles were made of a copper-silver alloy, and also displayed the raising technique. Unlike the pottery vessels, metal ones were susceptible to denting, and these specimens were no exception.

|

|

|

(left) CEREMONIAL VESSELS (LAMBAYEQUE) FUSION EPOCH These vessels are made of a gold-silver-copper alloy and silver, using a "sinking" technique. On the vessels the face of a deity with feline fangs and winged eyes can clearly be seen when the piece is upside down. Here are clickable thumbnails for two more pictures of these ceremonial vessels:

(left) MUSICIAN PLAYING PANPIPES [APOGEE EPOCH (1 AD - 800 AD) The so-called Indian flute, also known as panpipes, is a typical Andean musical instrument and to this day it forms one of the most important elements of Peruvian folkloric music. In ancient Peru this instrument was played in ceremonies. In Moche depictions of the dance of the dead or scenes associated with the underworld, musicians play the panpipes before a confrontation. This instrument is played in pairs, reinforcing the sense of a search for contact between opposites.

|

|

|

|

|

Decoration and Jewelry: It's Good to be Royal

The rooms devoted to decoration, clothing and jewelry were very interesting if a bit disorganized, and I'll take you through the exhibits pretty much in the order I found them. We begin, oddly enough, at death.

|

|

|

|

|

GOLD NOSE ORNAMENTS VICUS, FORMATIVE EPOCH (1250 BD - 1 AD) Vicus nose ornaments made from gold and and gold/copper alloys were hung from the cartilage between the nostrils. Their gold color and concentric circular decoration symbolized the jaguar, which was represented often in the art of ancient Peru, especially among the cultures of the Formative Epoch. The jaguar's pelt was represented in stone sculpture and pottery with the same circular symbols. Within the world view of South American culture, the jaguar has also been linked with the sun and, therefore, with gold.

TURQUOISE AND GOLD BREASTPLATE The personal adornments of the elite were manufactured from materials which were not readily accessible to the general populace. These pieces tell us that the elite enjoyed exclusive access to prestige items. Such items included seashells from tropical seas, such as Strombus and Spondylus, and gemstones such as turquoise and chrysocolla. |

|

GOLD EAR ORNAMENTS MOCHE, APOGEE EPOCH (1 AD - 800 AD) Throughout history and in many cultures, the human body has not only been decorated, but actually transformed through tattooing, piercings and deformations. Some parts of the body, such as the lips, ears and skull, have been modified through processes which last a lifetime. Ear ornaments wee one of the most significant adornments used to distinguish those individuals in power in Andean societies. When the Spanish arrived they called the Incan nobles "orejones" (literally, "big ears"). In reference to the size of their ears, which were enlarged by the adornments they wore. Some of these ear ornaments were so heavy and large that they were held in place by bands wrapped around the wearer's head. In Moche ear ornaments we can see magnificient work in the form of mosaics inlaid with gemstones such as chrysocolla, sodalite and turquoise, as well as mother-of-pearl and Spondylus shells. The diverse nature of the materials used in these exclusively prestigious ornaments indicates participation by the ruling elites in networks of long distance trade. The designs on the discs of the ear ornaments feature rhombuses, spirals, iguanas and bird warriors. Some of the rods of these ear ornaments were also finely decorated with depictions of ceremonial combat. |

|

| |||

|

|

The political and religious leaders of the societies of ancient Peru considered their power during the Formative Epoch. The members of the elite dressed themselves with crowns, breastplates, ear ornaments and rose ornaments made from gold and copper and when they died these objects which were part of their identity, went with them into the next world. In Vicus culture funerary contents, some crowns have been found which were deliberately bent in what we might call a "sacrifice" of the piece. As important symbols of the identity of the individual who was buried with them, these objects also "died" during the burial. The crown not only accompanied the deceased as part of their funerary attire; it also accompanied them through the transformation required for their entrance into the world of the dead. | |

|

SILVER ORNAMENTS (CHIMU) IMPERIAL EPOCH (1300 AD - 1532 AD) Ear ornaments were one of the personal adornments which most clearly indicated the status of those who wore them. Their quality, size and iconography communicated the social position and identity of the wearer. Silver Chimu ear ornaments feature scenes depicting the gathering of Spondylus shells from the sea, as well as representing a ruler or deified ancestor. This individual appears surrounded by step motifs symbolizing the sacred architecture of his burial site. Below are more pictures of these nose and ear ornaments. | ||

|

|

| |

|

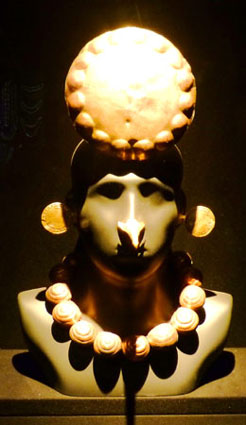

GEMSTONE AND SHELL NECKLACES NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN COAST (1250 BC - 800 AD) Necklaces made from gemstones and seashells adorned the leaders of the societies of ancient Peru and formed part of their funerary offerings. The stones used included black porphyry, blue sodalite, translucent quartz and blue chrysocolla, from different regions of Peru. They also used Spondylus shells from the warm waters of Ecuador. The use of these objects made from exotic materials differentiated the leaders from the rest of the population. To this end, the leaders controlled the trade networks, thereby ensuring their exclusive access to these materials.

|

|

|

SHELL AND BONE JEWELRY

From Peru's earliest times shells and bones were used to make beads which featured sophisticated and detailed designs. The majority of these depicted sacred animals such as birds, serpents, toads and fish. Human figures can also be seen.

These small pieces were used to make the necklaces, bracelets and breastplates that adorned the members of the elite. |

|

|

|

|

GOLD AND SILVER CROWNS AND ADORNMENTS CHIMU, IMPERIAL EPOCH (1300 AD - 1532 AD) In today's world, we consider gold a precious metal for economic reasons. However, in ancient Peru, gold and silver were acorded equal importance. Even weavings and seashells such as Spondylus enjoyed equal prestige. The attire of the leaderrs of ancient Peru was composed of a number of metal decorative elements made from gold, silver, copper and alloys. In nature, silver is not easily found in its pure metallic state, and great skill and technical knowledge are required for its processing. Silver was first worked a thousand years before Christ, but it was during the height of the Chimu Empire, from the 12th to the 15th century, that such exploitation reached its greatest level of technological sophistication. In societies like Chimu, silver was used in the attire of the nobility. Crown, diadems, breastplates, ear ornaments, nose ornaments, necklaces and bracelets formed th eofferings placed in the tombs of the elite. The iconography on their objects ws associated with the ancestor or deceased ruler, who would be surrounded by other figures with the forms or features of felines and birds. |

|

THE BIRD RUNNERS

One of the most fequently recurring themes in Moche art is the race between human beings or anthropomorphic beings with the features of animals, carrying bags with lima beans and sticks in their hands. In this race, the runners participated wearing their finest clothing and elaborate headdresses, one of the most characteristic of which was the circular frontal headdress.

At right you can see headdresses made of copper or a copper/gold/silver alloy, gold birds' beaks, breastplates with Spondylus shell beads, and a sculptural ceramic representing a bird runner. |

|

|

|

MOCHE, APOGEE EPOCH (1 AD - 800 AD)

|

|

|

|

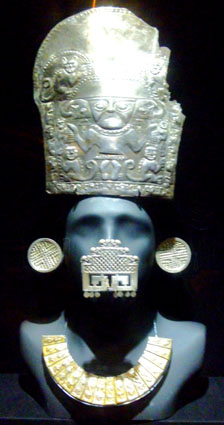

GOLD HEADDRESS/EAR ORNAMENTS CHIMU, IMPERIAL EPOCH (1300 AD - 1532 AD) This group of gold Chimu adornments includes a headdress with lateral elements which resemble the crests or wings of birds. The main design of the headdress is composed of a feline face with a bird's beak. Serpents hang from the ear ornaments. Here we see the trinity formed by a feline, bird and serpent, the three sacred animals of ancient Peru. This piece displays the supreme power enjoyed by the great lords of the past. There are clickable thumbnails below for some closeups of the faces on some of these ornaments:

|

|

GOLD FUNERARY OFFERINGS VIRU, FORMATIVE EPOCH (1250 BC - 1 AD) These adornments belonged to funerary offerings found in Viru tombs, and they are among the oldest gold objects found in southern Peru. In some tombs ingots or sheets of gold were also placed in the mouth and hands of the deceased, as part of the funerary rites. Here we see a shirt adorned with gold disks, a crown decorated with gold strips (unrolled and hung on the wall), gold plume-like headdresses, gold earrings, gold nose ornaments and gold necklaces. Click on the thumbnails below to see more of these gold items:

|

|

GOLD FUNERARY OFFERING CHIMU, IMPERIAL EPOCH (1300 AD - 1532 AD) The Chiu were the greatest metalworkers of ancient Peru. This is the only known complete set of gold Chimu clothing in the museums and private collections of the world. The little that is known about its origin indicates that it was once part of the funerary offering of a great lord who was buried in th emud brick city of Chan Chan, the capital of the Chimu kingdom. It expresses all the great splendor of th epower enjoyed by the ruler who wore it, together with his symbolic relationship with the sun. This elaborate dress includes plumes in the crown and the borders of the breastplate. These plumes represented birds, which were believed to be the only creatures able to approach the sun. The ear ornaments feature a repeated image of the face of the great lord of Chimu seen from the front; in the epaulettes he appears standing and seen from the front, holding decapitated heads in each hand. In the plumes of the crown and breastplate a procession of individuals shown in profile with feline features and wearing half-moon headdresses can be seen. |

That brought our tour through the Larco Museum of Pre-Columbian Art to a close, as we walked through the last of the exhibit rooms, crossed through the atrium you saw earlier, and back out into the bright sunlight in front of the museum. I hope you enjoyed going through the exhibits with us.

To finish with the remainder of our last day here in Lima, please click the link below to return to that page:

|

Return to November 22, 2014: A Museum Tour of Lima |