|

Artwork Aboard the Jewel of the Seas |

|

Our Stateroom on the Jewel of the Seas |

|

Return to the Caribbean Cruise Master Index |

Traveling to Chichen Itza

Taking the Tender to Playa del Carmen

|

|

I prevailed on a fellow tourist to snap a picture of Fred and myself on the tender. Then we were off. This time, the ship was moored only a mile or so away from the dock at Playa del Carmen; I suppose it all depends on the geography of the harbors and straits as to how close the ship can come. As we motored in, Fred got a good view of Playa del Carmen. The tender dropped us at the Playa del Carmen dock where we walked just a short distance to enter Playa del Carmen.

Walking to Our Tour Buses

When everyone was present, we started off in our two-abreast line. The dock area at Playa del Carmen is way too crowded for the tour operators to bring lots of big buses in, so we walked about eight blocks along the beach and then a couple of blocks inland to a parking area were our buses awaited. Along the way, Fred took some interesting pictures of the main walking street along Playa del Carmen's beachfront, and I have put thumbnails for four of the best of these below. To view the full-size picture, just click on its thumbnail. Don't forget to close each picture window when you are done.

|

On the Bus to Chichen Itza

|

Our route was going to take us down the coast a ways on what turned out to be a relatively new express highway to the town of Tulum. There, we turned inland on a two-lane highway to the town of Coba, where we had a rest stop.

From there, we headed generally west, and I think the route above is pretty accurate. We bypassed the large town of Valladolid (on a bypass, no less) and eventually saw the signs for Pista and Chichen Itza.

When our bus pulled out from Playa del Carmen, we first had to navigate some fairly narrow streets to get to one of the main streets that would lead us out to the main highway. While we were navigating through town, our tour guide, took some time to get to know us by entertaining us at the outset with a bit of schtik- obviously something he'd had to do many, many times before.

|

|

But, after all, we had almost a three-hour ride ahead of us, so his explanations and entertainment were welcome- particularly since we'd brought nothing to read during the trip.

After a short time, we got away from the beach and out to the main expressway. I was surprised (although I guess I shouldn't have been) to see all the familiar franchises out near the main highway- including McDonald's, Wendy's, Sam's Club and Costco. But we reached the expressway south and headed off. The expressway was pretty normal, except for one oddity. At each of the exits (which looked pretty much like ours do) the through traffic still had to slow down to go over a pair (or sometimes more) of speed bumps. Why they had built them on the expressway I couldn't say. We found the same thing when two-lane highways went through towns, but I could see more justification for them there. (Although I did wonder why simple speed-limit signs wouldn't have worked just as well.)

At the town of Coba, the bus pulled into the local equivalent of a Stuckey's, and most everyone got off the bus to get a snack or use the facilities. There were a lot of souvenirs for sale, some of them rather odd. I'm not sure what all the tourists thought.

Back on the bus, we went through a number of small towns and farms, until we began seeing signs for Chichen Itza and some other destinations that I knew Fred was wondering if we could visit.

It was another hour before we pulled into the parking area and our group formed up at the entrance to Chichen Itza.

Exploring Chichen Itza

Introduction to Chichen Itza

History

Itza rule brought about drastic changes in the internal structure of Yucatecan communities. At the same time, the introduction of an innovative view of the world marked the establishment of an order characterized by changing commercial values, production and distribution systems, and residential and religious architecture of the groups in power.

It is calculated that during the age of grandeur approximately 50,000 inhabitants were spread out over an area of 15 square miles, including such distant groups as those of Balamkanche, Iki, Cumtun, Poxil and Halakai, among others. All of them were connected to the ceremonial center by means of roads known as sacbeob.

Chichen Itza has been widely studied, and excavated and restored more than any of the other Mayan cities. Yet its history is still clouded in mystery and there are many contradicting theories and legends.

When Chichen-Itza was first settled it was largely agricultural. Because of the many cenotes in the area, it would have been a good place to settle. During the Central Phase of the Classic Period, referred to as Florescence, (625-800 A.D.) arts and sciences flourished here. It was at this time that Chichen-Itza became a religious center of increasing importance, evidenced by the buildings erected: the Red House, the House of the Deer, the Nunnery and its Annex, the Church, the Akab Dzib, the Temple of the Three Lintels and the House of Phalli.

Toward the end of the Classic Period, from 800 to 925 A.D., the foundations of this magnificent civilization weakened, and the Maya abandoned their religions centers and the rural land around them. New, smaller centers were built and the great cities like Chichen-Itza were visited only to perform religious rites or bury the dead. The Itza people abandoned their city by the end of the 7th century A.D. and lived on the west coast of the peninsula for about 250 years. However, by the 10th century A.D. they returned to Chichen-Itza.

The Mayas who lived in Chichén-Itzá built many palaces, temples, and monuments. They not only were powerful warriors but also wise men who studied the stars and left a written record of their history in the form of carved glyphs. Many kings governed the city and gave orders to construct higher and higher buildings. As the Mayas were great artists, they painted them with many colors and decorated them with beautiful sculptures. In many of them you can see a feathered snake. It was its main god named Kukulcán.

Around 1000 A.D. the Itza allied themselves with two powerful tribes, Xio and Cocom, both claiming to be descendants of the Mexicans. This alliance was favorable to the Itza for about two centuries. During this time, the people of Chichen-Itza added to the site by constructing magnificent buildings bearing the touch of Toltec art: porches, galleries, colonnades and carvings depicting serpents, birds and Mexican gods.

The Toltecs originated from Central Mexico, and one respected theory suggests that the Toltecs invaded Chichen Itza and imposed their architectural style on new constructions. Alternatively, we know that the Maya traded extensively and it is possible that they were influenced by the Toltecs in their own architecture. Another more recent theory claims that Tula, capital of the Toltecs, was actually under the domination of the Maya, resulting in a transfer of style from one city to another. There are fragments of evidence to support each line of thought, but no conclusive evidence for any single theory.

The priests had an observatory built in the shape of a shell to study the stars and foretell the future. They also had their own ball games. To practice it they built a great ball court with walls and stands. They played with rubber balls that they should pass through rings of stone. Only the kings, the priests, and the most important warriors lived in the great palaces. The common people lived in huts made of straw located near the pyramids.

The Toltec influenced the Itza in more ways than just architecture. They also imposed their religion on the Itza, which meant human sacrifice on a large scale. They expanded their dominions in northern Yucatan with an alliance with Mayapan and Uxmal. As the political base of Chichen-Itza expanded, the city added even more spectacular buildings: the Observatory, Kukulcan's Pyramid, the Temple of the Warriors, The Ball Court, and The Group of the Thousand Columns.

In 1194, Mayapan broke the alliance and subdued Chichen and Uxmal. Suddenly, and in the space of only a few years, the Mayas of Chichén-Itzá decided to leave their city. Archaeologists do not know why but they left and the city remained silent in the middle of the Yucatan jungle.

The Ruins

The ruins are divided into two groups. One group belongs to the classic Maya Period and was built between the 7th and 10th centuries A.D., at which time the city became a prominent ceremonial center. The other group corresponds to the Maya-Toltec Period, from the later part of the 10th century to the beginning of the 13th century A.D. This area includes the Sacred Well and most of the outstanding ruins.

The ruins of Chichen Itza are federal property, and the site’s stewardship is maintained by Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, INAH). Oddly enough, however, the land under the monuments is privately-owned by the Barbachano family.

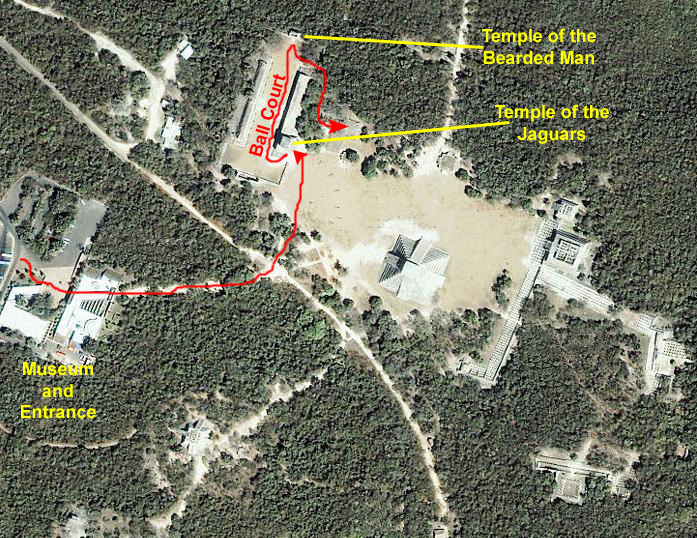

Entering the Site

|

|

The Temple of the Jaguars

|

|

|

Having just said that I wouldn't try to stick to a time sequence for the pictures, I should say that sometimes I found it was easier to go ahead and show some of the pictures at the time they were taken, rather than group them with others of the same thing. I'll be showing you our route through the site as we go, and I don't want to confuse you by dropping in some pictures that were obviously taken earlier or later. As an example, as we were gathering in front of the Temple of the Jaguars, we had an excellent view of the iconic Pyramid to Kukulkar, and so we each used it as a backdrop for a picture of the other. Here is my picture of Fred and here is Fred's picture of me.

|

Located next to the ball court, this temple owes its name to a procession of jaguars carved on the front of the upper structure. These motifs were probably associated with the military order of the "Tiger Gentlemen" imported from Central Mexico by the Itzá. The doorway to the upper temple is marked by two large serpentine columns and opens to a series of chambers. These are now closed to the public to protect the colored paintings which cover the walls. These paintings show military scenes from Chichén Itzá's history.

The lower building, or annex, is a small enclosure which is entered through a doorway of carved columns. The columns are decorated with military chiefs who carry lances and dart throwers plus several carvings of the god Kukulcan. The statue of the jaguar at the entrance is believed to be a ceremonial throne, a seat of honor for the lord of Chichén Itzá. Many believe that the governor sat on this throne and presided over public and religious ceremonies and met with diplomatic couriers from other parts of the Yucatan. At it height Chichén Itzá was a powerful commercial and political force in the region. Here is another view, showing the jaguar statue and myself.

The back wall of the annex has a colored fresco which shows a dignitary seated on his throne with rows of warriors carrying the common weapon of Central Mexcio, the dart thrower. Some researchers believe that this fresco illustrates the conquest of the city by the Itzáe. At the corners of the upper part of the structure are the omnipresent serpent heads, the serpent being a very common motif throughout the site.

Fred was very interested in the intricate carvings here and throughout the site, and periodically I will include a group of the pictures he took of them. This first set of thumbnails is for the carvings on the Temple of the Jaguars. Click on the thumbnails to view the full-size pictures:

|

Our guide has finished his explanation of the Temple of the Jaguars and we are moving off in this direction, around the end of the temple building and into the Ball Court.

The Ball Court

|

|

|

Upon entering the ball court, visitors are struck by the excellent accoustics of the stadium and its surrounding temples. The panels along the side walls are decorated with scenes from the ball game and its players. One of the scenes, the beheading of a player in center field witnessed by the players of both teams, is one of the most dramatic examples of Maya art. The scene not only illustrates the horror faced by the players but also the sacred importance of the game. At one time it was believed that the losers were destined to die but new theories have been proposed by researchers. Some think that the captain of the winning team was sacrificed since his team's triumph made him a fitting offering to the gods.

An essential part of the Juego de Pelota are the two stone scoring rings decorated with serpents which are found on opposite walls of the ball field. The serpent is a repeating theme throughout the Chichen Itza site. For example, when you come around the side of the Temple of the Jaguars, you can see, at the corner of the temple adjacent to the Ball Court, a large serpent head sticking out from the building. As you come around it into the Ball Court itself, you can see the body of the serpent resting atop the slanted carvings that line the field. Finally, if you step back and look up, you can see the part of the Temple of the Jaguars known as the Upper Temple.

Nobody knows exactly how the game was played but is believed that for a team to score, the players of that team had to pass a hard rubber ball through the openings of the rings; a team member could only hit the ball with elbows, wrists or hips (thus making the game different from either football or soccer). Although played for sport and for wagers the ball game had a definite religious significance. In the Maya creation story, the Popol Vuh (divine twin heroes) play this same game for their lives against the lords of the underworld.

Although ball courts are found in many Maya cities in the Yucatán, none are as large or well reconstructed as the one at Chichén Itzá. Indeed, there are eight other much smaller ball courts at Chichen Itza, but this one was deliberately built on a much grander scale than any others. The length of the playing field here is 400 feet, and two 25-foot-high walls run alongside the field.

|

|

Some people think the captain of the losing side was executed by the winner; others suggest that the winners earned an honorable sacrifice. No one knows for sure. It is said that the game was used either as a method of settling disputes, or as an offering to the gods, perhaps in times of drought. Only the best were selected to play, and to be sacrificed in this way was a great honor.

Imagine, then, the significance of this giant court, where the goals are 20 feet high and the court is longer than a football field. The acoustics here are superb; a low voice at one end of the court can be heard clearly at the other end and the atmosphere during a game must have been electrifying. It is said that only the noblest could attend the court itself, the general population having to listen from outside.

During our guide's explanation, he indicated that some researchers connect the activities in the Ball Court to a place we will be stopping at shortly- the Platform of the Skulls- believing that the platform was used for the sacrifices resulting from the game. But, again, this is just speculation.

There were lots more carvings here, of course, and I've put a set of thumbnails for the pictures Fred and I took of them below. Click on the thumbnails to view the full-size pictures:

|

The Temple of the Bearded Man

|

The Temple of the Bearded Man forms the north boundary of the Ball Court, and it has a platform 14 meters long and 8 meters wide. On top of this is a base with inclining walls and a central staircase. The staircase panels are decorated with trees, butterflies and birds topped by a square panel with figure of Kukulcán representing the man-bird serpent.

The temple itself is 10 meters long and 6 meters wide and consists of a single room with a vaulted roof. The front of the temple has a sloping wall face and a vertical wall. These architectural elements are common in other parts of Central Mexico and may bave been introduced by the Itzá. The back wall of the temple is decorated with a variety of religious scenes showing a bearded lord and the serpant god Kukulcán. There are also warriors with arrows and several seated dignitaries in the guise of eagles.

The Platform of Skulls

|

|

The central panel of the the platform is carved with three horizontal rows of skulls. There are also representations of eagles and warriors carrying human heads in their hands. The function of the platform was to exhibit the skulls of enemies and sacrificed prisoners, and so the carved decoration served as a reminder of the aggression of the military chiefs and as a terrifying warning to anyone who might attack the city. Unlike the racks in the Central High Plains, this platform displays the skulls inserted in a vertical fashion, one above the other. This impressive custom resulted in the creation of lasting monuments to significant acts of war and sacrifice, and reflected the obvious intention of frightening neighbors and potentially rebellious subjects.

Our guide told us that no two of the carved skulls are exactly alike, and this is all the more amazing when you figure that there must be more than 1500 different skulls along all four sides of the platform. He also mentioned that during the excavation of the platform several actual human skulls as well as a statue of the mysterious Chac-Mool (the purpose and meaning of whose image has still not been identified) were discovered.

From our position at the Platform of Skulls, there was a really good view of the Temple of the Jaguars, so Fred had me pose using it as a backdrop.

The Platform of Eagles and Jaguars

|

The figures of eagles and jaguars devouring hearts are said to represent the warriors who were responsible for obtaining victims for sacrifice to the gods. The "Eagle Knights" were archers who attacked the enemy before other soldiers fought hand to hand. The aggressive sculpted eagles found on the walls of the platform are the symbol of these elite group of archers who stood out on the battlefield because they wore clothing of feathers from the bird for which they were named.

The "Jaguar Knights" were believed to be the most fierce members of the army, modeled after those found elsewhere in Central Mexico, and there are many carvings of them on the sides of the platform. They fought hand to hand, with wooden clubs tipped with knives of obsidian. They covered themselves with armor made of jaguar skins and helmets of jaguar heads. The figures of jaguars represented the soldiers who were often charged with obtaining prisoners for sacrifice to the city's gods. These sacrifices took place on the platform itself and, like the other platforms, there were multiple stairways leading to the top.

The Sacred Cenote

|

Just east of the Platform of Eagles and Jaguars there was a pathway heading north. I had missed any sign (if there was one) and it looked as if this was just an area of vendors. But I stopped and asked some returning visitors what was at the end of the path. It turned out to be the Sacred Cenote. The path is actually the route of an ancient sacbe (road), and leads to the cenote- a sinkhole in the limestone bed that is partially filled by water coming from an underground river. These cenotes were very important to the Mayans as their main source of water and had great religious significance. Here, we found a deep almost circular hole with steep sides and murky green water beneath. We discovered that this cenote was not one of those used as a water supply.

The legendary Sacred Cenote of Chichén ltzá was special to the people for its religious and social significance. On occasion, the sacrifice of human life was part of the offerings made to the god of water. Nevertheless, such sacrifices were not as common as had earlier been imagined. There are stories of sacrificial victims being thrown into the cenote, along with offerings of treasure. In 1901, an American, Edward Thompson, bought the land around the site and proceeded to dredge the cenote. He found jewelry, pottery, figurines and the bones of many humans, mostly children. An international dispute arose when he shipped the findings to the Peabody Museum at Harvard, where some still remain (the remainder have since been returned to the Mexicans). The evidence, however, was inconclusive as it was feasible that children were at least as likely to fall into the cenote during play rather than as a deliberate act of sacrifice. He concluded that the 16th Century Spanish priest, Diego de Landa, had been wrong in his writings about the site.

According to Diego de Landa, "Into this well the Mayas were and still are accustomed to throw men alive as a sacrifice to the gods in times of drought; they held that they did not die, even though they were not seen again. They also threw in many other offerings of precious stones and things they valued greatly; so if there were gold in this country, this well would have received most of it, so devout were the indians in this." Quoted by Roman Chan in his book The City of the Wise Men of the Water, de Landa also described the cenote by saying that "this well is seven long fathoms deep to the surface of the water, more than a hundred feet wide, round, of natural rock marvellously smooth down to the water. At the top near the mouth, is a small building where I found idols made in honour of all the principal buildings in the land, like the Pantheon in Rome. I found sculptured lions, vases and other things, so that I do not understand how anyone can asay that these people had no tools."

According to historical Mayan sources, this natural well as an important ceremonial center and pilgrimage destination between the 5th and 16th centuries. Rituals were conducted here and offerings were made of gold, copper, tombar (a kind of brass), obsidian, quartz, shell, wood, copal, rubber, textiles and skeletal remains, mainly of children and adult males. There is no mention in these sources of live sacrifices, however.

The nearly circular pool is 190 feet in diameter, and the water level is 65 feet below the rim of the cliffs. The depth of the water varies between 20 and 40 feet. So, although no one knows for sure, it seems that the early inhabitants preferred to offer semi-precious stones, metal and clay objects to the gods of water, rather than human sacrifices. All of the offerings which were found were either broken or damaged as a part of the sacrificial ceremony. The objects (and perhaps the occasional human victim) were thrown to the cenote from the platform next to the altar, which is still in partial existence, and which you can see in my movie below of the Sacred Cenote. Part of this temple was adopted as a ritual bath, where the participants were purified.

|

|

As we came back out of the pathway to the Sacred Cenote, I noticed what looked like a a cord of stone logs, piled up just as wood logs would be. I have no idea what they were or what they might have represented or been used for. Near to these stone logs, we found also a a reclining stone figure that had been enclosed inside a metal fence. Also in this enclosed area were two serpent heads. We were not sure why this figure was here but, since it was adjacent to the Platform of Venus, it may well have been a representation of that celestial object. I found it interesting that the facing the Kukulkar pyramid, but I don't know what significance, if any, that might have.

The Platform of Venus

|

This is a square-shaped platform with steps on all four sides, each with balustrades ending in serpents heads and whose bodies are represented in the upper section as being plumed and sinuous in form. These serpents are found in combination with fish figures. Mythical creatures, (a combination of jaguar, eagle, serpent and human forms) adorn the center of the side panels. In each corner there are glyphs associated with the planet Venus. It is closely related to the Castle and Sacbe.

To the Maya, the planet Venus was both a heavenly body in their astronomical measurements and a mystical element in their mythology. Its importance can be seen in the care with which the sunrise is represented in this monument. The cycle of the planet was one of the basic elements used to establish a calendar for both public and ritual functions. This platform, more than 25 metres on each side, is also known as the Tomb of Chac-Mool, a name given to it by the archeologist who uncovered the first statue of this god in Chichen ltza in the late 19th century. Chac-Mool, whose real name and meaning is still unknown, probably came from Toltec imagery, since similar idols have been found in Tula and other cities of central Mexico.

The Pyramid of Kukulkan: North and East Sides

|

The Legends of Kukulkan

In that same year, Mayan stories recorded the arrival of a king named Kukulkan, the Serpent God, whose return had been expected. Kukulkan defeated the Mayan city tribes, and made Chichén Itzá his capital. The large heads of Kukulcán can be found in the newer part of Chichen Itza. These sculptures can be seen at the foot of the stairway to The Castle, as well as on many of the platforms and other buildings.

The Pyramid of Kukulkan: North Views

|

At mid-aftertoon on the days of the Equinox the shadow that covers the northeast angle of the pyramid is reflected on the stairway and forms triangles of light and shade that imitates the movement of a serpent. This effect is more impressive because it touches the large head of Kukulcán (the serpent) at the bottom of the stairway, making it seem as though the serpent was slowly and magically descending the pyramid. This effect could only be obtained by precise architectural and astronomical measurements. Stepping back, you can see that the large head merges into the low wall going up the steps giving the impression of a long serpent snaking down the pyramid.

|

|

The Castle is actually composed of two structures superimposed on one another. The later pyramid was built over an earlier structure. The newer pyramid is about 200 feet on a side, and has nine stepped sections (terraces) rising up to 80 feet. Archaeologists believe that the nine different floors symbolized the "Region of the Dead" to the ancient Maya. In the Temple of the Red Jaguar, an earlier temple over which the present Castillo was built at a later date, archeologists discovered the throne of the jaguar (which may have been a throne for the high priest). and a sculpture of the mysterious Chac-Mool figure (one of fourteen examples which are found throughout Chichén Itza).

One of the greatest experiences of visiting Chichen Itza has always been climbing the steep stairs to the top of the pyramid. Not only was it a somewhat mystical experience (as some Internet research discovered), but obviously the climber would then have an excellent view of the surrounding area of Chichén Itza. Climbing up also afforded visitors with the opportunity to visit the upper temple with its many images of Chaac, the Maya rain god. Years ago, the Mexican government excavated a tunnel from the base of the north staircase, up the earlier pyramid’s stairway to the hidden temple, and opened it to tourists, but in 2006, this access was closed and the only way to get to the throne room was by climbing the outside stairs. In 2006, however, a woman fell to her death while (or after) climbing the stairs, and as a result even the outside stairs were closed to access. So has ended one of Chichen Itza's best experiences, that is, unless one of the two access paths is reopened.

At the foot of the northern stairway are found the giant serpent heads representing Kukulcán, the god of the Maya-Toltec conquerors. At the top of the northern face, the upper temple has three openings, and these three openings are duplicated on the southern face. The eastern and western faces have only a single opening. These doorways have lintels of sapote wood covered with elaborate carvings and and ornamented with sculptured figures. All of these are much worn away, but a headdress, ornamented with a plume of feathers and portions of the rich attire still remain.

After viewing the pyramid from the northwest, we started to move around to the eastern side, and I caught a different view of the pyramid from the northeast corner.

The Pyramid of Kukulkan: East Views

|

Below are thumbnails for four more views of the Pyramid of Kukulkan taken from the northeast corner. You can click on those thumbnails to view the full-size pictures.

|

The Temple of the Large Tables

The Temple of the Warriors

|

Situated next to the Temple of the Large Tables, the Temple of the Warriors owes its name to the rows of pillars displaying relief carvings of warriors. It was erected over an ancient structure known as the Temple of Chac Mool, upon whose walls and interior pillars there are richly-colored carvings of plumed serpents, warriors, and priests. The upper building only partially reflects its true grandeur. There are three sculpted masks with extremely long noses on the outer walls and at the corners. On the inner walls of the vaults there were murals with scenes of war and daily life. The altar tables and benches may have served as seats and thrones for dignitaries.

The Temple of the Warriors complex consists of a large stepped pyramid fronted and flanked by rows of carved columns depicting warriors. This complex is analogous to Temple B at the Toltec capital of Tula, and indicates some form of cultural contact between the two regions. The one at Chichen Itza, however, was constructed on a larger scale. At the top of the stairway on the pyramid’s summit (and leading towards the entrance of the pyramid’s temple) is a Chac Mool.

The pillars here are sculptured in bas-relief, and have retained much of their original color, although the murals that once adorned its walls have faded. The temple is surrounded by numerous ruined buildings known as the Group of a Thousand Columns. On one of the walls of the Temple of the Warriors in the newer part of Chichén-Itzá you will see another example of a stone carving of Kukulcán. The temple's facade is composed of a sloping elevation and a large wall which contain this example of a representation of Kukulcán--the feathered serpent.

|

The upper temple has two enclosures whose entrance is an impressive opening guarded by a statue of Chac-Mool . It is believed that offerings were placed on the stomach of the reclining figure who would act as messenger to the gods. At the main entrance there are two serpentine columns sculpted in the form of the feathered serpent whose bases are the heads and whose crowns are the tails of rattlesnakes.

|

|

Fred took a number of other pictures of the ornamentation on the Temple of the Warriors, and I've put thumbnails for five of the best of those pictures below. To view any of the full-size pictures, just click on its thumbnail:

|

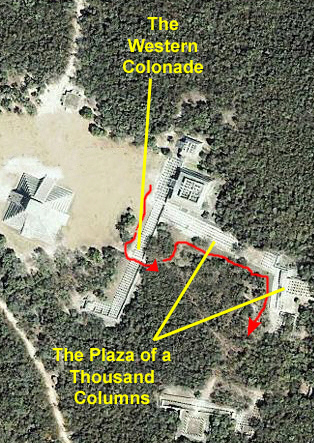

The Western Colonnade

|

|

|

|

The main facade faces the Plaza of the Castle, and a central corridor (shown in the aerial view) connects it with the Plaza of the Thousand Columns. There is a continuous bench seat running the entire length of the building along its eastern wall and, on its western side, walls in between the columns give evidence of later modifications. Its original use probably was to accommodate large gatherings during meetings, festivities and markets. It's hard for us to see, though, how much room was provided, since there are simply so many columns.

Nearing the central corridor we could look back along the front row of columns (shown here with Fred). Then, we turned to the east and started through the corridor, which is simply a wider space between two files of the columns. Passing the first rank of columns, we got a good view of the side of the Temple of the Warriors showing much more of the architectural detail of that building. Then, as we walked through the access corridor, we could look down the ranks of columns in both directions- north (towards the Temple of the Warriors) and south (towards the outlying sites). When we emerged from the corridor, we could look down the outside of the back wall and see how it was constructed and supported.

The Plaza of a Thousand Columns

|

The main characteristic of this structure is the ample valulted space held up by columns. It is probable that the function of this Plaza was civic and religious. Its construction is dated to the Late Classic/Early Post-Classic periods. It has a drainage system that gathers water and stores it in a natural depression northeast of the Plaza. Besides the main buildings, there are approximately 40 plinths (bases or foundations) which were built with stone from the buildings already in disuse in the Plaza. These are the remains of constructions built of perishable materials and must have served very diferent purposes than the original buildings since the spaces are very much reduced, perhaps as a center for humble inhabitants, living amidst the ruins of what was once a great city. This restored pillar was found lost among the aforementioned plinths.

The Northern Colonnade completely encloses the northern side of the Plaza and originally had a roof upheld by columns and pillars with basreliefs of warriors on the front. In the interior, one can observe a stone bench running along the length of the entire building and an altar with sculpted personages undertaking a ceremony with incense offerings. It has four accesses- two in front which communicate with the Plaza and two side ones which link up with the Temple of the Warriors and the Northeastern Colonnade The pedestal is decorated with basreliefs of eagles and jaguars devouring hearts.

The southern access and the juncture with other elevated columns to the north indicate that the Northeast Colonnade was used to isolate events that occurred in the plaza. At least two construction stages are evident in this sequence of buildings. In the first, there were four vaulted bays sustained by columns and stucco walls covered with multi-color painting. In the second, the two eastern bays were enclosed in order to build rooms on the second floor. The Northeast Colonade was incorporated during the period from 900-1200 A.D.

The outstanding sculpted figures make the Palace of the Sculpted Columns one of the most important on the east side of the Plaza. Its architectural characteristics denote a civic-religious function. It has a frontal gallery and a series of interior corridors. Originally, its three facades were decorated with geometric designs, carvings of dignitaries, and masks of a god with an impressive nose. Inside the palace, walls of subsequent construction stages close the space between the columns. This section of the Northeastern Colonnade upper floor of the Palace of the Sculpted Columns provides us with an example of the original decoration.

|

|

In addition to all the pictures of the plaza you've seen thus far, Fred took some very interesting detail shots of some of the carvings and other architectural details, and I've included some of those pictures here. All of them are interesting, and there are thumbnails for them below. To see the detail in the full-size image, just click on the thumbnail:

|

There was one last carving here at the Northern Colonnade whose meaning, other than the obvious one, escaped me. I couldn't find anyone to ask about it, and so I will just include this extremely interesting carving here. I can only make two observations about it. First, the games must have taken a long time to play; I am sure that carving the X and O symbols could not have been quick. The other observation is that, even though X was obviously cheating by taking more moves than he should have, he was such a terrible player that O won anyway! Click here to see this extremely interesting carving.

The Market

|

This section of the site is called "El Mercado," or "The Market," although its original use cannot be properly identified. What is obvious to researcers is that was closely-related to the Plaza in front, because the broad stairway leading up to it faced directly into the plaza itself- almost as if it had formed the southern boundary of the plaza area.

The entire area of the market site is raised up about six feet from grade, at least in the front. As you can see in this picture taken from the eastern end of the market platform, a sloping wall and stairway led from the plaza level up to the market level. I did not go all the way around the market platform, but my recollection is that when we were in the market itself, the back of it seemed to once again be at grade, so I assume that the land sloped at this point, and the builders chose to raise the front rather than lower the back to keep the market platform level.

|

This is one of the best examples of the "Gallery and Courtyard"-type structure found at Chichen Itza. Here, Mayan architects made significant construction advances, as in making wider vaultings and taller columns. It has a long frontal gallery with three accesses towards the plaza and one to the interior of the sunken courtyard. Near this access there is an altar with basrelief representations of personages. Surrounding the courtyard are very tall columns which supported the roof, made of perishable materials, and which sloped towards the sunken courtyard, which was drained by a cut stone canal. It was built in the Maya Toltec style between 900 and 1200 A.D.

|

|

The Southeastern Colonnade

|

|

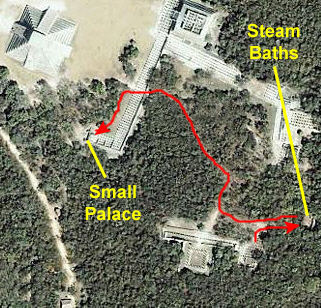

The Steam Baths

A Small Palace

|

Then, we'll come back up the path, pass back by the Southeastern Colonnade and the Market, and walk along the southwestern side of the Plaza, exiting through the same corridor in the Western Colonnade that we used to enter. We'll walk further down along the Western Colonnade and turn towards the Chichen Itza entrance to inspect a small palace or building that we saw before we came back here to the Plaza.

|

At the right is a waiting room, which was, presumably, used for dressing and undressing (such as was necessary). In the middle, you can see a raised stone platform, which was in the middle of the chamber used for bathing. The stone platform held the heated stones upon which water was thrown to produce steam. The stones were heated in the large fireplace that you can see at the left end of the building.

Here is a picture of me in the steam baths (this picture looking from the waiting area). And here is a view of Fred at the fireplace. Using him for scale, you can see how large it was. The rectangular hole in the back wall was not explained on any of the signage, but I would guess it was for ventilation or something like that.

At one time, the steam baths were covered over by a vaulted roof; you can see here how massive the supports for the roof were. Most of the roof was probably made of perishable materials, since none of it exists today and there are no piles of rock from a collapsed roof anywhere around.

|

|

|

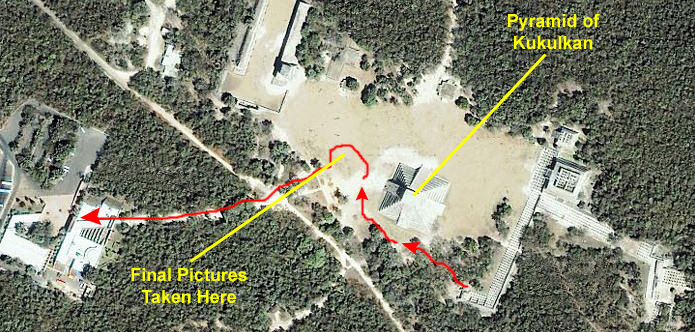

Our Final Stops at Chichen Itza

|

Then, it was back through the entry and visitor center and outside to the tour bus.

The Pyramid of Kukulkan: South Side

|

One thing that we learned was that the pyramid that we see now was actually constructed on top of a smaller pyramid of approximately the same shape. Why this was done, rather than building an entirely new structure, is unknown. Of course, we cannot see the interior structure except through the excavations that were made that resulted in the realization that there were indeed two pyramids here.

Looking at the pyramid from its southeast corner, you can see the same kind of deterioration on both of these faces. You can see the substrate of jumbled rock pieces over which the smoother blocks were fitted. You can see this construction even more clearly in this closup of the southwestern corner of the pyramid. Notice how the veneer of smoothed blocks is still in place right at the corner, but has fallen away (or been removed) further along the face. It seems as if the same thing has happened at multiple levels, all the way to the top, but why the corners have lasted longer than the faces no one seems to know.

The south stairway has deteriorated a great deal; even the stairway on the eastern side is in better shape. We did learn that climbing this face was never allowed, even when you could climb the northern face, and it is pretty obvious why. I could not get close enough to the pyramid to find out how loose the conglomerate beneath the facing stones actually is (although I would think if it were just loose earth, there would be even more destruction than there has been.

The Pyramid of Kukulkan: West Side

|

|

Some Final Views of Chichen Itza

|

|

Leaving Chichen Itza

Exiting through the services area back out to the bus parking, we paused within the breezeway of the building to take a couple of final pictures:

|

|

Then it was back on the bus for the return trip to Playa del Carmen.

Walking Around Playa Del Carmen

|

Instead, we were let off a few blocks out of the picture to the west, and our guide led us back to the main streets at the beach. From there, we pealed off and went our own way, walking along the crowded streets north, jogging down to the beach to view our ship, and then coming back south past an interesting church to the main street that leads down to the pier. There, I took a long movie of our walk from Carlos 'n Charlies down to the pier and past Senor Frog's.

The first group of pictures I want to include are the various street scenes that Fred and I took. Playa is very much a resort area- a vacation spot where most of the economic activity is directed towards tourists or the locals who are involved in running the shops and businesses that cater to those tourists. So you will see not only shops selling souvenirs and trinkets, but also street vendors selling food to the locals and adventurous tourists. You'll see some odd characters, such as "lizard guy"- a fellow sitting in a chair with his (presumably) pet lizards and a parrot while making a cell phone call, and the vendor charging tourists a fee to be photographed with his giant iguana. You'll even see a cell phone tower that someone has attempted to disguise as a palm tree.

We took other pictures along the streets as well, and you might want to look at some of them for more of a flavor of what Playa was like. Just click on the thumbnails below to view the full-size pictures:

|

At one street, we walked down the street past some beautiful tropical hibiscus to the beach where we could see the Jewel of the Seas anchored out in the harbor. This was such a pretty spot, that each of us used the beach, harbor and ship as a backdrop for a picture of the other, and you can see my picture of Fred here and Fred's picture of me here.

|

|

All too soon, it was time to go back to the pier and catch the tender back to the ship. Carlos 'n Charlies bar and restaurant is at the top of the street leading right down to the pier, and Senor Frog's is just before you get to the pier itself. I filmed a movie of our walk from the top of the street all the way to the pier.

Once onto the pier, Fred to a couple of views looking northeast along the shore at Playa del Carmen- one normal view and one closeup. He also got a picture of me with our tender in the background.

Tendering Back to the Ship

|

As we looked ahead, we could see the Jewel of the Seas riding at anchor, and my thinking about there being another tender was confirmed when we passed the other tender heading in to pick up more passengers. Because of the time the ship was supposed to sail, I assumed that would be the last run the tenders would make. The last view I took on the tender ride was one of Fred looking back at Playa del Carmen.

Today's excursion was probably the most interesting of all; I am sure it was for Fred, being as interested in Mayans as he is. It was really a once in a lifetime visit, but now I'd like to compare it to another famous ruin- perhaps Uxmal or Macchu Pichu- and I hope I'll get the chance to do that sometime.

When we got back on board, we immediately went to Greg's cabin to see why they'd missed the Chichen Itza excursion. We found that Grant had gotten sick the night before; he was still just lying in bed when we visited. So we related what we'd seen to both of them, and I'll send them a copy of this day's album page as soon as it is done.

For dinner, Greg had made reservations in Portofino- one of two specialty restaurants aboard ship. This one has an Italian theme, and the five of us (Grant was still not up to leaving their cabin) had a really good meal, after which Fred and I wandered around the ship some more before turning in.

You can use the links below to continue to another photo album page.

|

Artwork Aboard the Jewel of the Seas |

|

Our Stateroom on the Jewel of the Seas |

|

Return to the Caribbean Cruise Master Index |