|

October 27, 1992: Monument Valley and The Grand Canyon |

|

October 25, 1992: Mesa Verde and Silverton, CO |

|

Return to the Index for Our Western Trip |

The next morning we arose to a beautiful morning in a really great campground between the red cliffs east of Arches National Park to the east of us and the Colorado River on our west.

The Drinks Canyon Campground

|

There are 3 entrances to the camping area; we came in the middle one, which turned out to be close to the tent campsites and the payment station. We were fortunate, since the campsites are available on a first-come, first-served basis and since we arrived so late, that we had no problem in finding a good campsite right by the Colorado River. Perhaps this is because we were arriving on a Monday night, in the Fall, rather than a weekend night in the summer.

In the morning, which came crisp and cool, we awoke to see the scenery that we had been traveling through the night before- and it was spectacular, with the rather steep mountain cliffs east of us and the Colorado River to the west. It was a beautiful morning, and we spent a half hour taking pictures.

|

|

The campground was right at the edge of the river; you can see someone's tent along the shore in the background. The previous day's rain had disappeared entirely, and the sky was perfectly clear. It was just the kind of morning that campers love to awake to.

Of course we took a walk down to the edge of the river; knowing that this same river would, many hundreds of miles south of this point, cut the Grand Canyon, was pretty amazing.

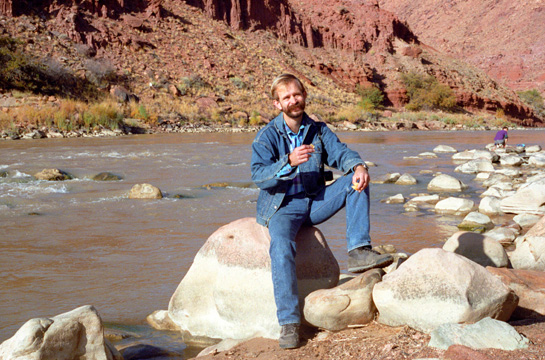

Here I am on the banks of the Colorado River at the Drinks Canyon campground. You can see more of the rock pillars on the other side of the river. |

Here's Fred having breakfast (an apple) beside the Colorado River. This picture was also taken at the campground. |

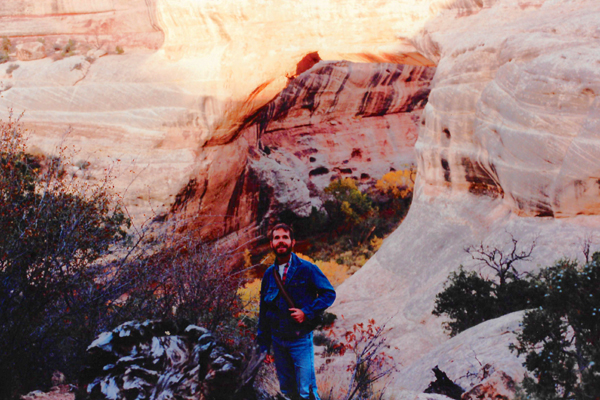

I thought the hills on the eastern side of the road were just too enticing to resist, so I asked Fred if we could take the time to scramble a ways up the hillside.

|

At this particular bend in the river, the land opened out for a bit, and that's why the campground was built here. I thought that the campground was really neat. It had a shaded area for the tent, early morning hiking and, of course, the river right beside us. It's not the river so much as the sound it makes; I found it extremely restful, and I got a great night's sleep. We would, in the future, stay in many National and State Park campgrounds. This one, simple as it was, turned out to be one of the best.

All the rocks and earth were very reddish, perhaps indicating the presence of iron, but that's not always the case. I think that the rock strata that you can see in the cliff on the far side of the river are also very interesting.

In the two pictures below, also taken from the hillside across the highway, both look upriver in the direction from which we came. You can see a good portion of the campground in each of them. The road, of course, is leading to Moab off to the left in each picture:

|

|

We returned to the campsite where the tent had been drying out in the morning sun, packed everything up, and then headed off down Highway 128 towards Moab. We stopped at a couple of places to take some pictures.

Some of the Cliffs on the Eastern Side of the Colorado As we headed South along the river, this was some of the scenery on the East. Some of the gaps in the pillars up there give a foretaste of what Arches National Park is going to be like. Even here, the action of wind is starting to carve some holes in the rock face. |

Looking Back North Along the River Here, you can get a better idea of what kind of scenery we must have been passing the night before. You can see clearly that if I had been looking out the driver's window all I would have seen is the sheer cliff on my left. |

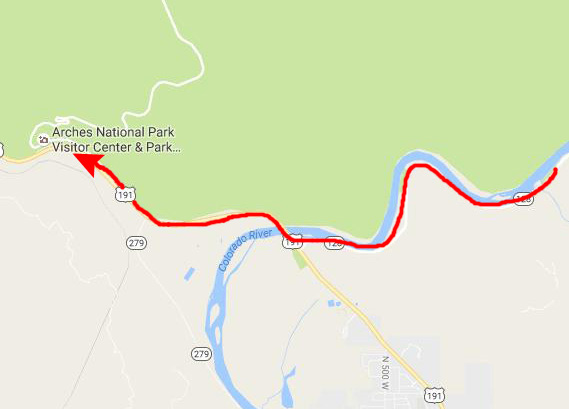

Our drive took us south to a couple of miles north of Moab, and then we turned northwest on US Highway&191 to get to the entrance to Arches National Park.

|

|

Arches National Park

Let me preface the pictures from our visit to Arches National Park with a copy of most of the park map. The map includes all the major tourist areas, although some of the backcountry areas have been cropped out. You can use this map to follow our stops through the Park and see where some of the arches that we saw were located relative to each other. That map is in the scrollable window below, with the entrance and Visitor Center at the very bottom:

|

Fred and I were of course far from the first visitors to Arches NP; plain ordinary rocks worn into fantastical shapes have attracted visitors to this area for thousands of years. The earliest visitors weren't just sight-seeing, though. Hunter-gatherers migrated into the area about 10,000 years ago at the end of an Ice Age. As they explored Courthouse Wash and the Salt Valley area, they found pockets of chert and chalcedony: two forms of microcrystalline quartz perfect for making stone tools. Chipping or knapping these rocks into dart points, knives, and scrapers, they created debris piles that are still visible to the trained eye.

We took quite a few pictures here in the Park, as we did basically two major things. First, we drove the Park Road all the way north to the Devil's Garden Trail trailhead, and second, we hiked the Devil's Garden Trail to see all the arches along it. (There was much more we could have seen, but we knew we would be back here eventually, and wanted to save something for then.)

The Drive North Along the Park Road

|

Then, roughly two thousand years ago, the nomadic hunters and gatherers began cultivating certain plants and settled the Four Corners region. These early agriculturalists, known as ancestral Puebloans, raised domesticated maize, beans, and squash, and lived in villages like those preserved at Mesa Verde National Park.

Few dwellings have been found in Arches, which was the northern edge of ancestral Puebloan territory, so it's possible they only visited seasonally - or that their dwellings have been lost to time. What does remain, though, are their drawings. Rock art panels are an invitation to wonder: Who made this? What were they thinking? Like earlier people, the ancestral Puebloans also left lithic scatters, often near waterholes where someone may have shaped tools while watching for game.

For a variety of reasons, people began leaving the region about 700 years ago. Descendents of the ancestral Puebloans include people living in modern-day pueblos like Acoma, Cochiti, Santa Clara, Taos, and the Hopi Mesas. As the ancestral Puebloan people were leaving, nomadic Shoshonean peoples such as the Ute and Paiute entered the area and were here to meet the first Europeans in 1776. The petroglyph panel near Wolfe Ranch is believed to have some Ute images since it shows people on horseback, and horses were adopted by the Utes only after they were introduced by the Spanish.

As you drive into the Park, the formations close to the entrance, which are pretty spectacular, taper off, and vast panoramic views open up; we took a couple of pictures to record these views.

Much of the landscape features isolated formations like this one, reminiscent of the type you find in areas like Monument Valley. |

In this view looking northeast from the Petrified Dunes Viewpoint, you can pick out Balanced Rock towards the left and at least two arches in the tall formations near the center of the image. |

The views here in the southern area of the park were pretty amazing, and we were closing in on the area of the Park where the more interesting formations and arches are located. In many of the views looking east, the mountains of western Colorado can be seen- along with their first snowfalls of the season. The first formations we passed were not the spectacular ones, until we got close to Balanced Rock.

The Southern Area of Arches NP From a distance, you can see many unusual vertical formations. These particular ones are somewhat unremarkable, although they are still, to a city person like me, beautiful. The scrub vegetation is typical of this high desert area. |

Approaching Balanced Rock We are closing in on some of the first really unique formations, one of which is that balanced rock that you can see in the left center of the picture. There is a stop there for it and that is where we are headed. This view looks mostly North. |

The first Europeans to explore the Southwest were Spaniards. As Spain's New World empire expanded, they searched for travel routes across the deserts to their California missions. One of these routes, called the Old Spanish Trail, linked Santa Fe and Los Angeles along the same path- right past the park visitor center- the route that today's that Highway 191 takes.

|

The first formation where Fred and I stopped was Balanced Rock where our park brochure told us there was a short trail that we could take around the formation. Before we headed out on the trail, Fred set up his tripod to get this picture.

Balanced Rock is one of the most popular features of Arches National Park, possibly because it is right next to the park's main road, about 9 miles from the park entrance.

The total height of Balanced Rock is about 128 feet, with the balancing rock rising 55 feet above the base. The big rock on top is the size of three school buses. Until recently, Balanced Rock had a companion- a similar, but much smaller balanced rock named "Chip Off The Old Block", which fell during the winter of 1975/1976.

Balanced rock was formed through a process known as weathering, and we wanted to take the trail around its base and photograph it and its companion formation from various angles. Here are some of the pictures we got of this unusual formation as we walked all the way around it and its companion spire.

Balanced Rock |

(Picture at left) I tried to catch the sun peeking over the top of the formation, which put this side in deep shadow. The top rock is balanced on the lower one, as that weak rock stratum between the two has been almost entirely eroded by the wind action in the park. There is just enough of a rock cradle left to balance the top stone (which must be made of some harder material than the lower portion). The bottom portion has many fractures, and it is just a matter of time before erosion or some earth tremor removes just enough of the support to topple the upper formation. Then, I suppose, they will have to change the name of it to "Fallen Rock."

(Picture at right)

|

Balanced Rock's Companion Formation |

The road to this area becoming a National Park began with glowing descriptions of the beauty of the red rock country put in print by Moab newspaperman Loren "Bish" Taylor, who took over the Moab newspaper in 1911 when he was just eighteen years old. Bish editorialized for years about the marvels of Moab, and loved exploring and describing the rock wonderland just north of the frontier town. Some of his journeys were with John "Doc" Williams, Moab's first physician. As Doc rode his horse north to ranches and other settlements, he often climbed out of Salt Valley to the spot now called Doc Williams Point, where views of the fabulously-colored rock fins were at their best.

Balanced Rock |

(Picture at left) Taken from around on the sunny side of the formation, this is a good view showing how the top boulder is supported by the bottom pedestal. From different angles the top boulder has different shapes; it's not round, but here it seems to resemble a big lump of bread dough. I think it is interesting how that intermediate stratum has eroded away at a faster rate than either the upper or lower portions. We in our century are catching this formation at what I am sure is the approaching end of its life. You can walk right up to the formation and look up, but that is just a bit unsettling.

(Picture at right)

|

Me Up on Balanced Rock |

Word spread. Alexander Ringhoffer, a prospector, wrote to the Rio Grande Western Railroad in 1923 in an effort to publicize the area and gain support for creating a national park. Ringhoffer led railroad executives on hikes into the formations; they were impressed and believed such wonders would certainly attract more railroad customers, so the campaign began. The government sent research teams to investigate and gather evidence. In 1929, President Herbert Hoover signed a presidential proclamation reserving 1,920 acres in the Windows and 2,600 acres in the Devils Garden for the purpose of establishing Arches National Monument. Since that time, the park's boundaries have been expanded several times. In 1971, Congress changed the status of Arches to that of a National Park, recognizing over 10,000 years of human history that flourished in this now-famous landscape of rock.

Balanced Rock was pretty neat; not only were there good views of the two formations from the trail around them, but there were also wonderful views looking out across the Park's southern section.

The View Southwest from Balanced Rock Here, we are looking back towards the entrance to the Park, generally towards the Grand Canyon area, and is typical of the wonderful vistas offered. |

Looking Southeast from Balanced Rock The road continues to end at the area where the actual arches are. We got our hiking things and set out on a circular trail that led us from one arch to another. Just after the start of the trail, this view beckoned. Almost all the erosion you see here is from wind action, since this area gets relatively little snowfall or rainfall. Those are the mountains of Colorado in the distance. |

The Arches Along the Devil's Garden Trail

|

The Devilís Garden Trail is the longest and most difficult maintained trail in Arches National ParkĖ but it was a heck of a lot of fun. Once we got past the early sections we were scrambling up and over long, narrow sandstone fins (future arches!), ducking under and crawling through existing arches, and trekking through ruggedly beautiful backcountry that few of the more casual tourists in Arches will ever get to see.

The trail began at the end of Devilís Garden Road, which is literally the end of the paved road in Arches National Park. Because this trailhead is also near the Parkís one campground, this can sometimes be the busiest section of road even though itís the farthest you can drive into the park without a 4WD vehicle. Even in the off-season, the trailhead parking can be a crowded affair, but we were lucky that we were here on a Monday in late October; we had no problem at all on the park road or at the parking area.

We'd read that the Devil's Garden Trail was a wonderful hike that allowed the hiker to see as many as six named arches, any one of which would be worth a moderately easy 4 mile hike. The main trail is well maintained, and wide. The very first spur trail took us to Tunnel Arch

|

All of the arches and formations we saw on our hike on the Devilís Garden Trail actually have been named, but by whom I have no real idea (and I don't think that at this point anyone really does). Here, the action of wind has carved a neat hole right through this rock formation. I can only assume that for some reason the rock in the center of the formation had a different constitution than the surrounding rock did for this hole to be formed. Nothing will happen to this formation for a very, very long time- save that the hole will grow steadily larger. This arch is in its infancy.

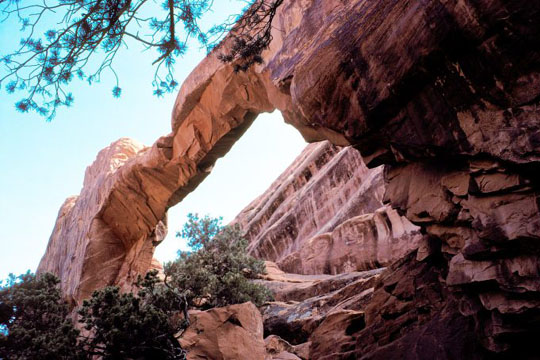

Right nearby was the second named arch on our trail- Pine Tree Arch (probably so named because there were a number of gnarled pinyon pine trees around the base of the cliff in which it has been carved.

Here is another center view of Tunnel Arch from a slightly different spot. You can see just how thick the arch actually is. |

Fred scrambled a bit off the trail to get this picture of Pine Tree Arch. It is interesting how the hole appeared at just the one place and nowhere else in the formation. |

After looking at these two arches, we returned the two-tenths of a mile back to the main trail and turned right to continue heading into the Devilís Garden. For the next half a mile, the trail maintained an easy-to-follow path heading toward the northwest. To our right the landscape was mostly flat, but to the left and straight ahead we could see the strange angular rock formations we found along the rest of the trail. From some angles, many of them look like the hoodoos I've seen pictures of at Bryce Canyon, but theyíre actually long, narrow sandstone fins. The pillar you see here was at the end of one of these formations, so there may, at one time, have been an arch here. Most of the arch formations we see in the park are birthed from these stone slabs; as the softer dirt and sand near them weathers away, the exposed sandstone is eroded by wind, sand, and water. The arches themselves are constantly growing as they continue to be eroded until they eventually collapse.

At the 1.4 mile mark, we came to the next named arch on this trail- Wall Arch- an impressive 71-foot-wide and 33-foot tall arch. We got two good pictures of Wall Arch:

|

|

As it turned out, we were fortunate to be able to see Wall Arch; in doing my Internet surfing to grab the maps and diagrams relating to our hike this afternoon, I discovered that Wall Arch collapsed (sorry, will collapse) on the evening of August 4th, 2008. Today, what hikers will see at this point in the trail us just the remains of Wall Arch. Odd that a formation like this would collapse in my lifetime. But this won't be the last time this will happen. Some years from now, just a year after Fred and I see The Old Man in the Mountain in New Hampshire, it, too, will collapse and disappear forever.

|

(Since this will be the only time in this album that I'll visit Landscape Arch, there are a few future events worth mentioning. First, in 2006, Landscape Arch will claim the title of longest arch when new measurements, done with lasers, would discover that it is actually three feet longer than Kolob Arch.

Secondly, Landscape's title will be in danger for a time in 2010, when a similar formation will be discovered in China- the Zianren Bridge- that is about 400 feet across. But fans of Landscape Arch will breathe a sign of relief when geologists categorize the Zianren Bridge as not an an arch at all, but a natural bridge.)

This arch is one of the thinnest in the world, only five feet thick at its thinnest. You can walk a short way up it, but there is a barrier to prevent you from getting out on the thinnest part of it. I think the arch is extremely graceful, the way it bulges at one side, like the beak of a hummingbird. From this vantage point, one has an excellent view of it. It is amazing to me that the wind could have carved such an intricate and fragile work of art.

Landscape Arch was really beautiful so we spent some time wandering around the area. There was a trail that took you right underneath the arch, so we followed that, and you could even go partway up the arch before being stopped by a sign forbidding hikers to go further out onto the arch because of the dual danger of falling or of rock collapse.

The Underside of Landscape Arch I though I would like to get a picture of the underside of Landscape Arch looking up at the bottom of it. I am impressed at how thin it actually is. It is amazing that it has continued to stand for so long, but I guess it will be standing for a while longer. |

Standing on One End of Landscape Arch The trail continued right across the base of Landscape Arch, and this gave me a chance to walk part way up onto the arch, to a point where there were markers indicating that you couldn't go any further. All the small formations around remind one of silent monuments or custodians for the beautiful arches in the park. |

Landscape Arch has had its own recent run-ins with erosion. Last year, a sandstone slab some 30 feet long fell from the most narrow section of the arch. If another such slab falls anytime soon, I can easily imagine the area under the arch being closed, so I am glad we have got our pictures now. From here, the trail left the level ground and climbed up one of those long, thin sandstone fins. We ascended about 250 feet in the next quarter mile to the next arch.

|

|

Nearby, we came to another sandstone fin and yet another arch- but this one was a double arch- Partition Arch (so named because there are two openings with a pillar between them.

|

Whatever it looks like to the individual hiker, it was a beautiful formation. The first thing I thought to do was to climb up and sit in the smaller opening so Fred could get a picture (and so I can give you a frame of reference for how big the openings actually are). That's the picture at left.

Evidently, the wind and the elements have bored these two holes next to each other for some reason. I suppose that as time passes, each will grow larger, and eventually coalesce into one classic arch formation. I am absolutely confident that I will not, however, be around to see it. This formation (which I thought looked like a pair of glasses) is right on top of one of the highest points in the Park. This particular view looks East out of the Park.

Partition Arch was immensely interesting and quite beautiful- especially when you look through the two windows at the landscape beyond, and so we stayed here for a little while, climbing around and taking pictures.

|

(Picture at left) Here is one of the openings in Partition Arch, seen a bit from the side as I climbed down out of the smaller of the two openings. This particular view looks somewhat north from this formation.

(Picture at right)

|

|

Me Inside an Opening in Partition Arch I had not known that Fred actually took two pictures of me sitting up in the opening. This one is in addition to the one above in which he capture both of the openings at once. |

A View Through Partition Arch This another of those views that made the trip to Arches worthwhile- a perfect framed view through an arch. This one looks back east towards Colorado. I can only guess at how far the view extends- perhaps a hundred miles or so. I think that the colors of the nearby formations, contrasted with the general blue of the far background make for a striking picture. |

That last view reminded me a great deal of the stone arch that was used as a time portal in the Star Trek TV series episode "The City on the Edge of Forever". We could have gone all the way around the Devil's Garden Trail and made a big loop, but we decided instead to head back pretty much the way we came. There were some very steep drop-offs along the trail, so we were careful.

Fred Along the Devil's Garden Trail Walking this trail makes you feel you're at the top of the world. At this height, the air was considerably cooler, and the sunlight more intense. Just a ways back from Partition Arch, Fred stretched out on a sunny rock near the formation. |

The Devil's Garden Trail As we trekked down from Partition Arch, I stopped to take a picture of the trail back to the beginning of the hike. You can see a tourist on the trail (actually a number of them) along the sides of the rock formation in the right center of the picture. |

As we were hiking back to the trailhead, I paused to get another picture of beautiful Landscape Arch. You can actually pick out one of the openings at Partition arch most of the way up the rocky cliff at the right of the picture, just under the light red rock stratum, and just above the peaked rock whose top is lit by the sun. There are also some other hikers to give scale to everything.

The Drive to Natural Bridges National Monument

Along the Park Road in Arches NP When we returned to the car, we stopped for a snack, and then began to retrace our route back to the entrance to the Park. Along the way, Fred caught this picture of what he thought were interesting rock formations and some Fall color in the trees in the foreground. |

An Impressive Rock Formation As we neared the entrance to the Park, we passed through and by a whole series of massive rock outcroppings like this one. This one reminds me of a huge hotel with a revolving restaurant on top. Notice how it appears that the entire rock has been sliced with a knife- how smooth portions of the side of the formation are. |

It was later on, when Fred saw this picture, that he told me that to him, it looked like a big ship, and I have to admit that once he said that, I couldn't imagine it as anything else.

The Park Road at Arches NP Further down the road to the entrance is this view, which looks all the way out of the Park towards the town of Moab, Utah. Ahead are more of the massive rock formations like those seen in the previous picture. |

The Three Gossips Formation in Arches NP We have already seen this formation, a picture of which Fred took on the way into the park. He took this view from a different perspective, and intentionally put the speed limit sign in the picture. The rocks seem to be standing like silent sentinels to our progress out of the Park. |

Once we reached the Park entrance, we turned South on US Highway 191 and went through Moab. We stopped there for gas and to visit what was recommended as the best local place for ice cream.

|

The scenery along Highway 95 was nothing short of spectacular:

|

We had absolutely beautiful views all along Utah Highway 95 to Natural Bridges National Monument. The scenery along this highway was just as impressive as at the campground this morning, or even in Arches, yet it was entirely different. I think that the combination of the clouds and the setting sun made for the outstanding views. After about 25 miles on Highway 95, we turned north on the park entrance road- Utah Highway 275.

|

We drove into the Park and stopped at the Visitor Center to inquire about camping and fees, paid our entrance and camping fee, and headed further into the park to the campground. There, we stopped to secure a very good campsite on the outer north edge of the campground. Then, we continued on to the Park Loop Road to go see our first Natural Bridge.

|

If we had visited this area 260 million years ago, we would be standing on the dazzling white beach of a sea which covered eastern Utah during the Permian geologic period. That line of cliffs running across the top of the aerial view is just a small segment of a much longer line that was part of the shore of this huge sea. We noticed the sweeping lines, known as crossbedding, that pattern the white sandstone. Crossbedding represents the down-current face of a sand dune, down which sand slips as the dune advances under the force of wind or water. Geologists debate whether the Cedar Mesa Sandstone formed under water or along the shore as windblown dunes. We could see ripple marks forming today in the mud left in the canyon bottoms by receding flood waters.

Although the waters of the warm Permian Sea supported abundant life, fossils are rare at Natural Bridges. If you have ever stood on the ocean shore, you may know why. A beach is classified as a high energy environment, where grains of sand continually grind back and forth with each sweep of the tide. Few organisms can survive such rough treatment; thus, few make it their home. Any plant or animal remains swept ashore soon wear away. If you examine the Cedar Mesa Sandstone with a hand lens, you may see that some of the sand grains are actually fragments of fossils. One type of fossil that is abundant in the streambeds of White and Armstrong Canyons is petrified wood. This wood washes out of the Chinle Formation, found high above the Cedar Mesa Formation. When the trees died, they fell into stagnant swamp water which prevented their decay. Eventually, silica derived from volcanic ash replaced the wood, preserving its grain in stone.

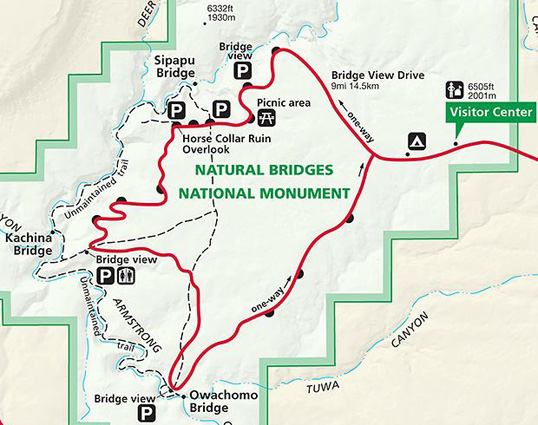

We drove around the Park Road, eschewing the first overlook so we could get to the first trail as quickly as possible. The afternoon light was already beginning to fail, and we wanted to get at least one hike in. We stopped at the parking area for the Sipapu Bridge Trail. Below are a copy of the Natural Bridges National Monument park map, so you can see where the Sipapu Bridge is located, and then beside that is an aerial view of just the Sipapu Natural Bridge and the area right around it. I've marked the natural bridge, another rock feature you will see in our pictures, and the approximate route of the trail.

|

|

The Park Road is a two-way loop; we headed first north towards the river course where the bridges have formed. We knew we wouldn't be able to see everything today, though. We stopped at the parking area for the first bridge (the Sipapu Natural Bridge) and got our stuff to hike down to it. We met a couple of people coming back, and after talking to them we felt that we could get down and back up before we lost our light.

|

The trail we were on, we discovered, is actually part of the Continental Divide Trail that runs along that geographic boundary through most of its length. We had actually seen a sign for the trail all the way back at Wolf Creek Pass two days ago.

The major difference between the natural bridges here and the arches we saw earlier today is that the natural bridges are formed by the action of water, while the arches are formed by the action of wind (and blowing sand). At the moment, the water flowing through this canyon is minimal, but this is the dry season. For this bridge to have been formed would have required a lot more water than we saw, over a much longer period of time. Fred is better at framing pictures than I am, and I think he did an excellent job with this one.

We saw earlier that arches stand on the skyline, but bridges form in the bottoms of deep canyons. Once water dissolves the cement between the grains of sand in a narrow fin of sandstone, frost wedging and gravity begin to work. While seeping moisture and frost shape arches, running water carves natural bridges. As the curving meanders of streams carved down into the sandstone, they undercut the canyon walls and bent back upon themselves until only a thin fin of stone separated them. Flash floods periodically pounded against weak spots formed by the soft siltstone layers in the sandstone. Eventually, the water cut through the narrow neck of the meander, forming a natural bridge. At first each bridge is thick and massive, as is Kachina Bridge, but as erosion attacks them on all sides, the bridges become more delicate (as with Owachomo Bridge) and eventually collapse.

|

|

As we walked down the trail, Fred and I wondered just how old these natural bridges were. From our little guide, we learned that the Owachomo Natural Bridge (which we hope to see tomorrow) is the oldest, but how old is that? Geologically speaking, the bridges themselves are relatively recent and short-lived occurrences. Since sandstone erodes at different rates (more weathering occurs when the climate is wet than during times of aridity), the exact age of the bridges is difficult to determine. We do know that ten million years ago the Colorado Plateau was flat and featureless. When the last glacial period ended 18,000 years ago, glacial melt and increased rainfall speeded the erosion of canyon country. A wet climate between 900 and 4,000 years ago probably began the erosion of most spans; the largest spans, like Sipapu, are believed to be over 5,000 years old.

|

|

As I maneuvered my way around the riverbed at the bottom of the canyon, I moved to one side so I could get a good view of the rock formation "upriver" from the Sipapu Natural Bridge. From my time in Fort Lauderdale, watching the yachts go underneath the downtown bridge, this formation took on the shape of a cabin cruiser, and it looked for all the world as if it was just motoring along about to go under a bridge.

It looked amazingly like a deep sea fishing boat; I could see the hull with the tapering bow, the aft section where the fishing chairs would be placed, the cabin and the radar dome on the top. The more that I look at the formation the more it looks like a motorboat to me. Even the base rock looks like the wake that such a boat would create. I have learned that the dark stripes down the rock are actual lichens that are growing on its surface.

|

I am learning that southeastern Utah is a land not only of texture, but of radiant color. In the hills, pale greens mingle with grey and white, and mesas glow with the red of the setting sun. Much canyon country color derives from the presence of iron in different combinations with oxygen.

The original sediments may have been drab, but they contained a small percentage of iron-bearing minerals. Groundwater later weathered these minerals, and oxygen rusted the iron a brilliant orange-red. Without enough oxygen, iron turns green. When iron combines with both hydrogen and oxygen, it becomes yellow-orange limonite.

Beneath the multi-colored mesas, the Cedar Mesa Sandstone appears startlingly white. The waves of the ancient sea washed nearly all of the darker minerals away, leaving only white quartz sands behind.

The canyon we are in is White Canyon, and down its walls streaks of red, orange, black and brown "desert varnish" run in a patterned tapestry. One theory is that water pours off the mesas during rainstorms, allowing bacteria to grow. These microorganisms combine iron and manganese with oxygen and fix these particles to the cliff walls, producing the shiny surfaces which often served as canvases for the petroglyphs of early Puebloans.

From underneath Sipapu Natural Bridge, we began to make our way back up the trail. A short way up, when we were about level with the bridge itself, I turned to take one last photo of Sipapu Natural Bridge in the fading afternoon light. By the time we got back to the top of the trail, the light had pretty much disappeared, so we drove the rest of the way around the loop road in the dark and went back to the campsite. We set up the tent in the light of the truck headlights, and then Fred cooked a dinner of chili, which, like all outside meals, tasted delicious. We cleaned up everything and then hit the sack. Although the day had been warm enough, the evening got nice and cool, and sleeping was not difficult.

You can use the links below to continue to another photo album page for our Western Trip or return to the Index to continue through the photo album.

|

October 27, 1992: Monument Valley and The Grand Canyon |

|

October 25, 1992: Mesa Verde and Silverton, CO |

|

Return to the Index for Our Western Trip |